‘The Isle of Wight’: An island of 20th-century miracles

Simon Calder spends a week visiting islands around the UK. Part 3: The Isle of Wight

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.A relic from a distant age – blessed with a sunny disposition, charm and humanity.

No, not me; the Isle of Wight.

Islanders are different. They tend to live life at a gentler pace, and change comes slowly. While it is temptingly easy for visitors crossing the Solent to observe that England’s largest island seems chronologically adrift from the rest of the UK, it is much more serious than that: the Isle of Wight is actually locked into the 20th century.

Start with the journey to the chalk raft sitting pretty in the Channel. You could hop on a ferry from Lymington, Southampton or Portsmouth. But that could mean missing out on what could be your one opportunity to hover.

As the “white heat of technology” seared through Britain in the 1960s, a couple of transportation miracles were created. One was Concorde, aimed at flying the rich and glamorous at twice the speed of sound. The other was the hovercraft – intended to transform maritime travel around the coast of Britain, across the Channel (with 60 cars and hundreds of passengers) and on short sea crossings around the world.

They had two more attributes in common: ferocious noise and formidable fuel consumption. But unlike the supersonic jet, the hovercraft lives on: half boat, half hairdryer, looking like a 1960s vision of how to solve the riddle of mass global transportation.

That dream has hovered off over the horizon, but every half-hour Solent Flyer or Island Flyer hoists her skirts and shuttles over from Southsea. Your ticket to Ryde buys 10 minutes (or, on a rough day, 20) of skimming across the waves – before subsiding with a mechanical sigh on the beach.

The leading resort on the Isle of Wight is also the northern terminus of the Island Line, another piece of transportational weirdness. The only surviving scheduled passenger railway line is barely eight miles long, but it manages to squeeze in eight stations – starting at the end of Ryde Pier and curving around the eastern side of the island to Shanklin.

You would not expect 125mph expresses, but many visitors are astonished to find that the entire passenger rolling stock was built before the Second World War.

Trains constructed in 1938, which had rattled up millions of miles on the Bakerloo Line, have somehow burrowed under the Solent and popped up to serve the people of the Isle of Wight and their summer visitors.

Get there soon if you want to witness the strange sight of a 1930s train trundling along a Victorian pier; they are due to be replaced next year. But the 20th-century theme remains: they will be superseded by District Line stock from the 1980s.

I was heading west, though, so I took the Coastal Path that meanders through meadows and villages from Ryde across to Cowes. On this stretch at least, the trail for cyclists and pedestrians is “coastal” in the same sense that the M1 is a coastal motorway: it stays well away from the water’s edge. But the sea-shy lanes guide you to Quarr Abbey, the greatest permanent glory on the island.

The Cistercians planted their spiritual flag on the Isle of Wight in the 12th century; their abbey was duly dissolved four centuries later by Henry VIII, leaving a skeletal ruin that haunts a field.

Yet a far more mighty replacement was created in the early 1900s. Benedictine monks from Solesmes in north-central France fled persecution and settled on the Isle of Wight, creating a new monastery from two million Belgian bricks. With Byzantine flourishes, it soars through the woodland towards the heavens – and even in these difficult times embraces visitors in need of tea, inspiration or reflection.

“It’s best not to expect anything from us,” said a young artiste on the island 50 summers ago.

“If you expect something, then you might not see it. Then quite naturally you’re going to be disappointed.”

The speaker was no philosopher. But he was the world’s greatest guitarist.

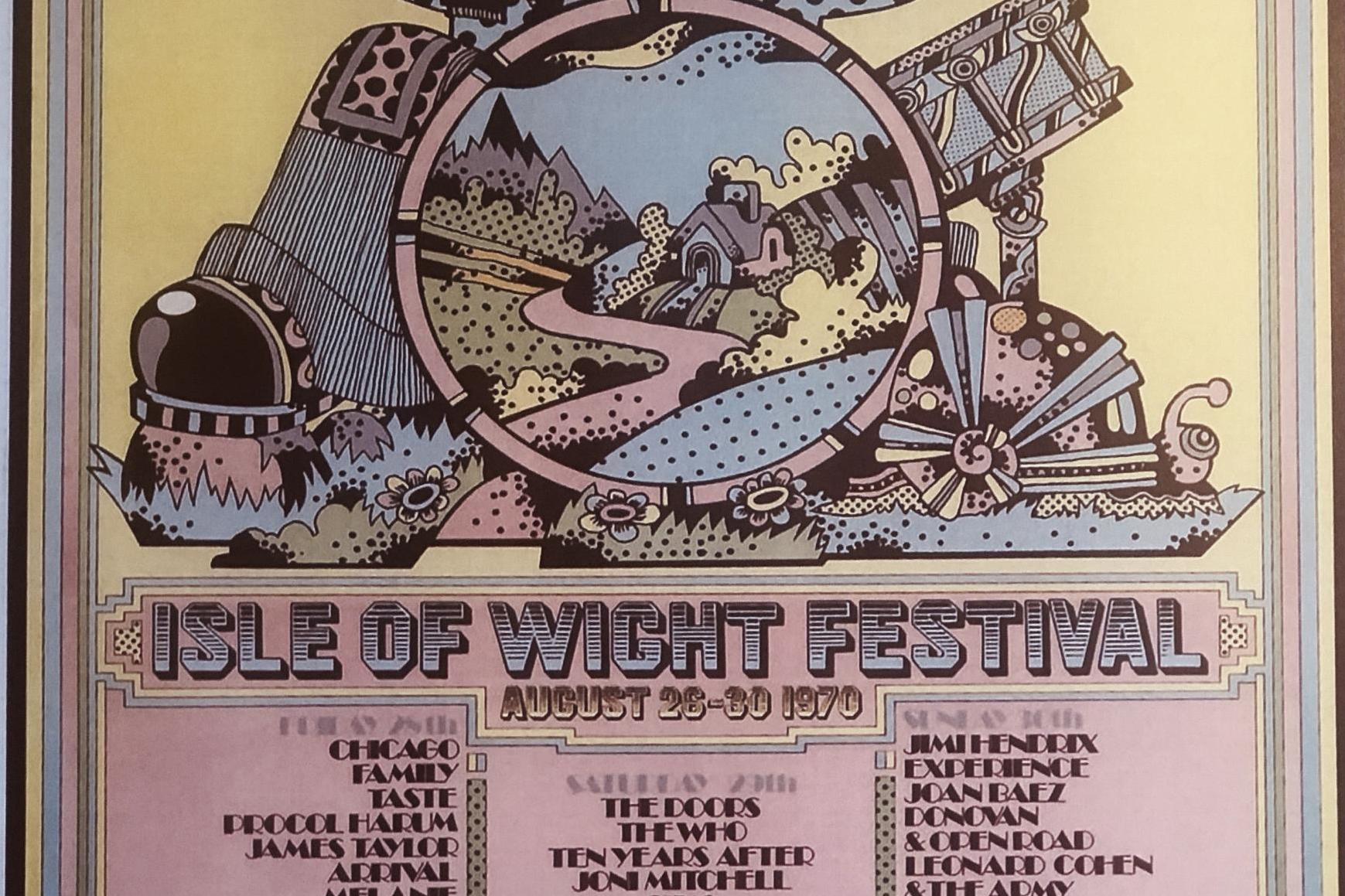

Jimi Hendrix was the main attraction at the biggest pop festival the world has ever seen. Inexplicably and ludicrously, the British response to Woodstock 1969 was to host an even longer and bigger event on East Afton Farm, a difficult-to-reach southwest corner of the island.

Somehow 600,000 people found their way to the large field, a mile long and a quarter-mile broad, that was chosen as the venue for the 1970 Isle of Wight Festival. Many had £3 tickets for five days of entertainment (which actually extended to six as the schedule unravelled), some did not.

A loose coalition of White Panthers (1960s anti-racists), French anarchists, and, bizarrely, Young Liberals launched a series of guerrilla raids, culminating in the fences being torn down and the festival being declared free.

“Open the gates, and for God's sake let's have some music,” announced the compere, Rikki Farr.

Despite sanitary facilities that, by day six, comprised a near-lethal biohazard, everyone survived.

“If you can remember the Isle of Wight 1970, you weren’t there,” say some. Others insist it was “The Last Great Event”.

Time will judge, but the Saturday line-up alone gives an idea of the pedigree: The Doors, Emerson Lake and Palmer, Free, Miles Davis, Sly and the Family Stone, The Who and Joni Mitchell, who ticked off the rowdy crowd: “You're acting like tourists, man – give us some respect.”

Real tourists on the Isle of Wight were appalled. ”My parents were on holiday there without knowing about the festival until they arrived,” recalls Rebecca Halpern.

“My dad was annoyed as people camping on the golf course meant he couldn't play.”

It was the last day of August by the time Jimi Hendrix could play. The music deity strode on to the stage, improvised God Save The Queen and electrified the weary crowd. But within a month he had died a sad and squalid rock star’s death at the age of 27 – uncared for by companions, overpowered by drugs.

A few months later, the government passed the Isle of Wight Act to ensure the island’s tranquillity could never again be shattered. The legend, though, survives as another wonder on an island of 20th-century miracles.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments