Bristol street art class lets you make believe you're Banksy

Criminally fun: Lizzy Dening gets to grips with graffiti in the city that spawned the world’s best-loved street artist

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Graffiti is the sexy cousin of fine art. It’s the college dropout that arrives on a motorbike, in a fug of cigarette smoke, to take you on a night out you’ll never forget. The closest I’ve ever come to being a “street artist” was carving my own name into my school desk (child genius I was not). So, when I heard about a graffiti tour and workshop in Bristol – home of British street art – it seemed like an ideal way to unleash my inner naughty schoolgirl.

Graffiti, which blossomed here after being featured on American hip-hop album sleeves but can arguably be traced back to cave paintings and hieroglyphics, is still for the most part illegal – amazing considering it colours almost every wall in the city. Here, it’s used to convey the concerns of residents, from national politics and fears about capitalism to homages to deceased friends. The artists’ feelings are, quite literally, writ large.

I got a glimpse under the city’s skin on a walking tour, run by Where The Wall and led by local artist Alex. He was cagey about which work was his, but he’s definitely felt the adrenaline-rush of a hastily sprayed image, and has the anecdotes to prove it. My favourite: learning never to spray on a windy day after giving a nearby silver Mercedes a dusting of red paint.

Graffiti artists have developed ingenious ways of evading the law. When Right and 45RPM wanted to paint an elaborate design on a busy street, they disguised themselves in plain sight, wearing hi-vis jackets and hard hats. “You can get away with anything, wearing a lanyard,” teased Alex, tapping his own.

It’s this police-dodging that’s responsible for the popularity of stencils: they can be prepared at home, take mere minutes to spray onto a wall and – crucially – you can achieve great results in the dark. They were first used in the 1980s by French artist Blek le Rat, although they’ve since been made famous by Bristol’s own Banksy.

And it was this local lad who created the UK’s first piece of legal graffiti, Well Hung Lover. He carried out this work hidden under a blue tarpaulin, right in the eyeline of the city council – a body hated by any street artist worth their spray can. The council wanted it gone but bohemian Bristolians voted against its removal, a move which riled some other street artists, who felt that Banksy had become a darling of the middle classes while they were still treated as vandals. One paintbombed the work in protest.

I loved learning about the creativity of the different techniques used, from “dusting” (flicking spray) to freezing your cans to make them expel a fine mist. You can even throw household cleaners at your finished work to distress it. We explored an alley where young sprayers had been honing their craft – possibly the Connor Harringtons or Tats Crus of the future. I certainly have a new respect for the daubing at my local train station.

But like most modern art, street art is less about the technical skill (although there are examples of that in abundance) and more about the message. While the ecograffiti of Moose – a Mancunian who uses a high-pressure washer to stencil patterns onto polluted walls – is beautiful, its location is what tells the story. You’ll find it on the very same police station where the authorities had come down hard (without success) on 73 adolescents in 1989, resulting in the own goal of inspiring many Bristol teens to pick up their first can.

After years of arrests, it’s funny to think that today’s kids are being encouraged to let out their inner vandal during spray art classes.

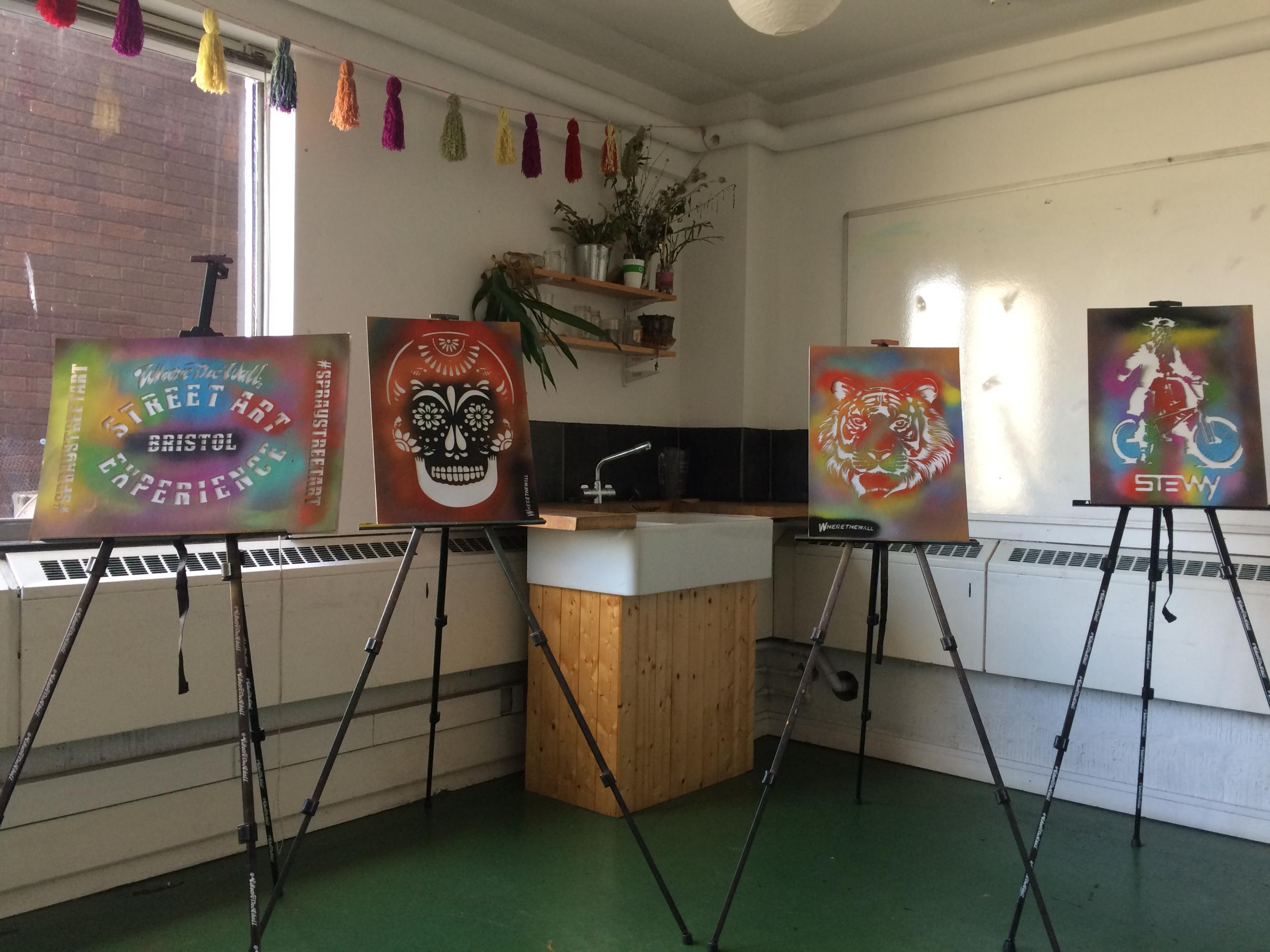

It’s something that I was now even more keen to try, putting theory into practice in a graffiti workshop. The room was bustling with a mixture of ages, including one former teen rebel (street name: Up Most) passing his spray-can-torch on to his kids – they took to it like ducks to water-based paint.

I chose an extremely detailed tiger stencil (options were varied, including a Mexican skull, bird and a Banksy copy) and set to work with pink and blue stripes. These non-toxic sprays needed to be wielded with a quick wrist. Finally, my years of excessive hair spraying were paying off.

It took all of 15 seconds to finish (a much better rate of return than hours of fruit bowl watercolours) and the joy of peeling the stencil off was somewhere in between pulling a scab and revealing my wedding dress. My inner rebel had been officially activated. Now I come to think of it, there’s a bridge by my house that’s looking a bit bare…

Travel essentials

Staying there

Lizzy stayed at Beech House (urban-creation.com/beech-house-bristol), which offers luxury boutique apartments in the heart of the city. Studios from £145, room only.

More information

The two-hour street art tour costs £9.20 per adult, £4.80 per child. Tickets for the one-hour spray art class start from £12.50. To book, visit wherethewall.com.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments