Bradshaw’s railway timetables 1839: Rhodri Marsden's Interesting Objects

The national timetable aimed to rein in rampant confusion within an uncoordinated system

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

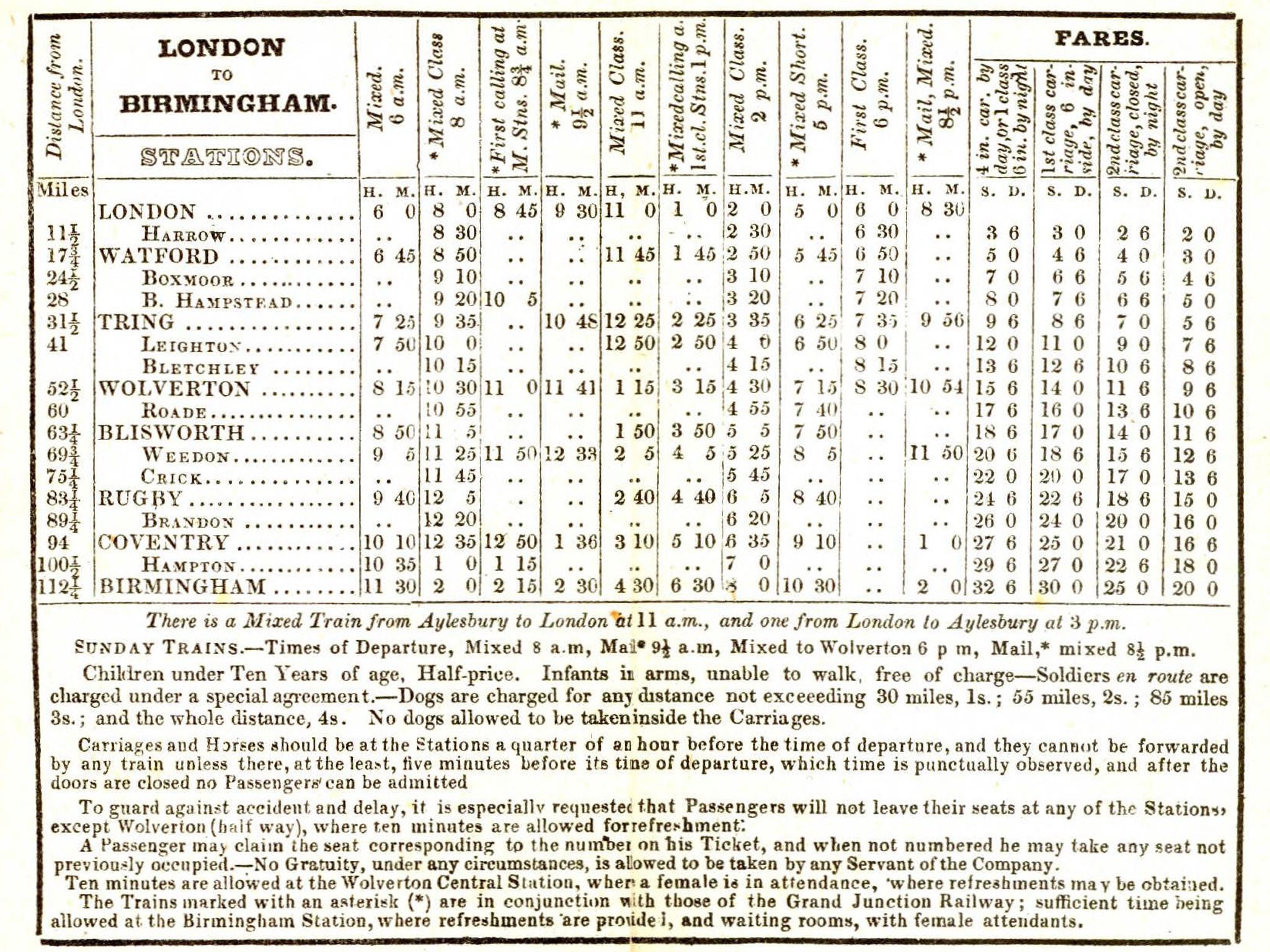

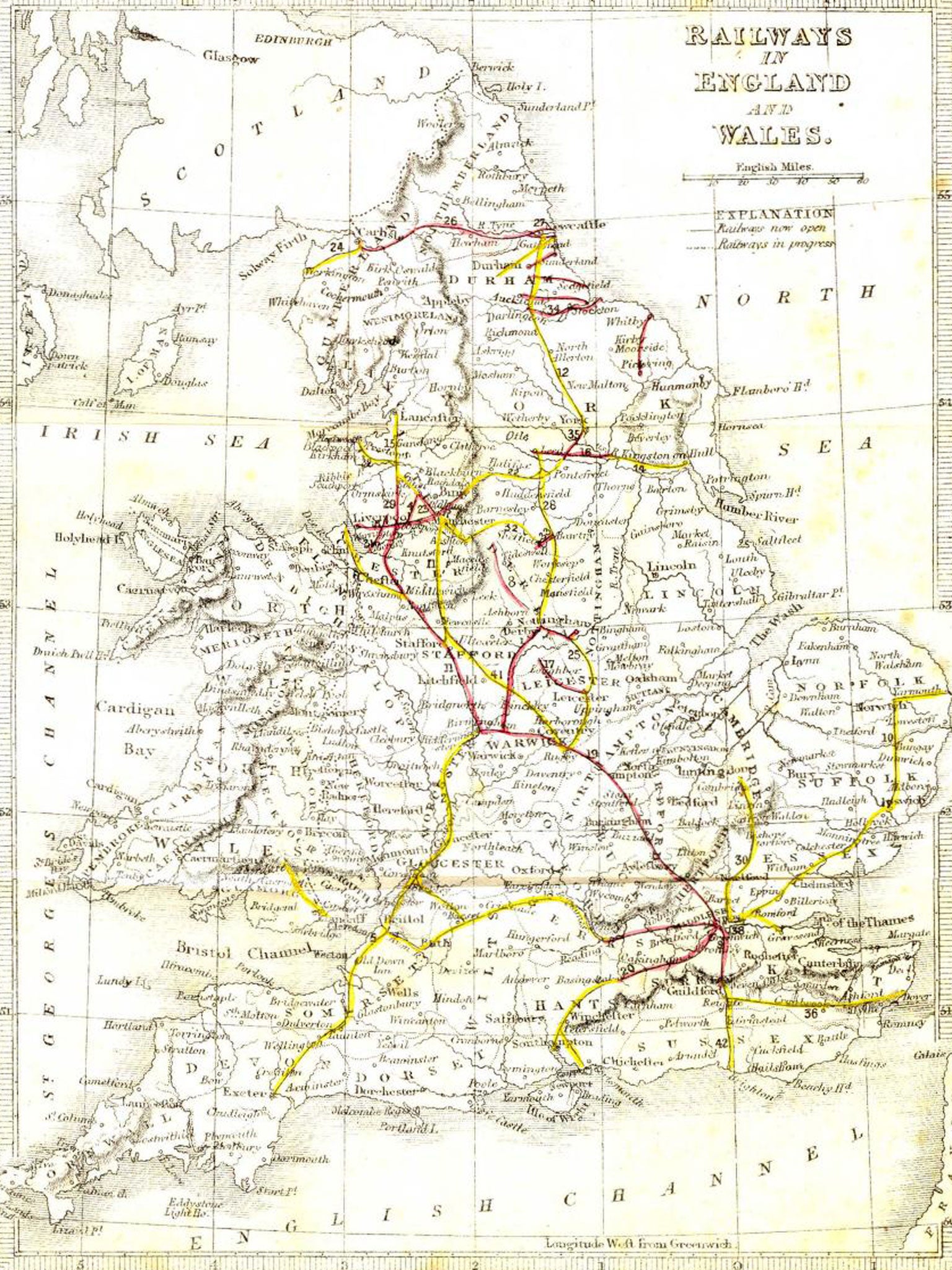

Your support makes all the difference.The 1830s saw a boom in railway building in England, as local companies seized their chance to establish themselves within a burgeoning national rail network. A national timetable, however, did not appear until this weekend in 1839. Bradshaw's Railway Time Tables, which included train times for both the north and south along with an "Assistant to Railway Travelling with Illustrative Maps and Plans", aimed to rein in rampant confusion within an uncoordinated system. "The necessity of such a work is so obvious as to need no apology," wrote Bradshaw in the introduction.

But while the necessity of a national timetable was obvious, it raised one fundamental and thorny question: what time is it? Back then, time was set locally according to the sun, so when a train left London at 6pm it was already 6.05pm in Oxford. One local railway guide of the era included an addendum indicating the number of minutes to be added or subtracted en route, so Tring was "2m slower than Euston" but "5m faster than Birmingham". Prior to the railway era, these differences weren't much of an issue. But now, travellers found that their watches were hopelessly unsynchronised.

It was reported that one local railway director refused to supply his train times to Bradshaw, saying: "I believe it would tend to make punctuality a sort of obligation." The 1839 Bradshaw's indicates that margins for error were built in, with all passenger trains listed as departing at multiples of five minutes past the hour – but this state of affairs wasn't sustainable.

In November 1840 the Great Western Railway imposed Greenwich Mean Time (GMT) on its stations, and by September 1847 "Railway Time" was used across the network. As a consequence, local time was no more. By 1855, 98 per cent of British towns were using GMT.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments