High-speed rail: What are the plans for HS2 and HS3?

The government has leaked details of its ‘Integrated Rail Plan’. What does it mean for the future of train travel?

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.The prime minister says the government’s Integrated Rail Plan constitutes “the biggest transport investment programme in a century”.

Boris Johnson claims it will deliver “meaningful transport connections for more passengers across the country, more quickly”.

These are the key questions and answers.

Define ‘high-speed rail’?

UIC, the global railway organisation, says the era was born on 1 October 1964 when the Bullet Train started running in Japan between Tokyo and Osaka. Its original running speed was 130mph (210km/h).

In the 1970s, the UK was ahead of Europe with rolling stock actually called High Speed Trains running on the Great Western line linking London Paddington with Bristol and Cardiff. It established 125mph (201km/h) as the benchmark for Inter-City rail in the UK.

Although the ill-fated Advanced Passenger Train and the Pendolino trains on the West Coast main line are capable of 140mph (225km/h), there has never been enough capacity to allow them to run at full speed in passenger service.

France made the next giant leap on 27 September 1981, when the Train à Grand Vitesse started running at a maximum speed of 162mph (260 km/h). This has since increased, with 186mph (300km/h) now common on high speed railways across Europe.

“High speed rail” is now generally regarded as speeds at or above 140mph (225km/h) on dedicated tracks.

How is Britain doing?

The only line that qualifies by the modern definition is High Speed 1, linking London St Pancras with Kent and the Channel Tunnel.

But in 2009 the last Labour government specified High Speed 2 (HS2) to connect the capital with the Midlands and north of England.

The project had all-party support, with the incoming Conservative transport secretary, Justine Greening, saying: “If this country is to out-compete, out-produce and out-innovate the rest of the world then we cannot afford not to go ahead with HS2.

“Put simply, we must invest in our transport network, not in spite of the economic challenges we face, but as a means to overcome them and to secure our country’s economic future.”

In total 345 miles of new high-speed track was planned for HS2.

Since then the cost of the project has more than doubled and is now approaching £100bn.

How much faster?

HS2 is planned for running at 225mph (362km/h), with the following schedule planned (current times also shown):

- London-Manchester: 67 minutes (125 minutes), saving 46 per cent on current journey times.

- Birmingham-Manchester: 40 minutes (87 minutes), saving 54 per cent.

- London-Glasgow: 220 minutes (269 minutes), saving 18 per cent.

- Birmingham-Glasgow: 200 minutes (240 minutes), saving 17 per cent.

- London-Liverpool: 94 minutes (132 minutes), saving 29 per cent.

Where will HS2 go?

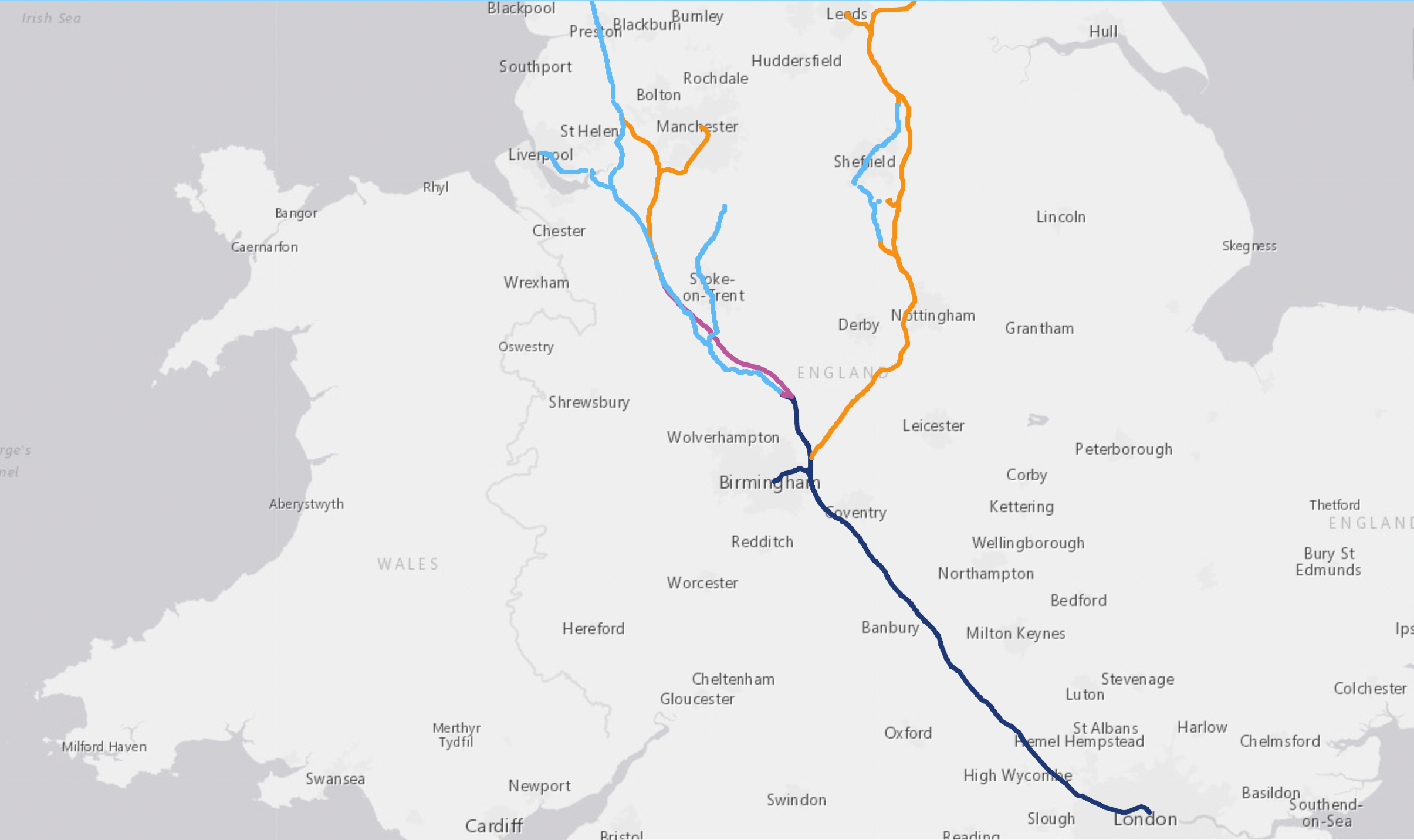

Its first stage is from London Euston to Birmingham. The twin-track line follows a more southerly trajectory than the existing West Coast main line and Chilterns line, cutting through rural countryside to a new Interchange station in the West Midlands, adjacent to Birmingham airport, where the line splits.

The western leg (HS2W) runs to Crewe and Manchester. Some high-speed trains will then run on conventional lines onwards to Preston, Carlisle, Edinburgh and Glasgow.

Meanwhile the eastern leg (HS2E) was expected to continue to Nottingham, Sheffield and Leeds – relieving pressure on both the Midland main line (to and from London St Pancras) and the East Coast main line (serving London King's Cross), and connecting to the existing line to York and Newcastle.

It included a new hub for Nottingham and Derby at Toton, which HS2 said “will be one the best served stations on the high speed network”.

What has happened to HS2E?

It has been axed, with instead a spur planned from Interchange to East Midlands Parkway, where high-speed trains will run on existing tracks.

From London to Sheffield, the journey with HS2 was planned for 87 minutes, saving 27 per cent on the current journey time of almost two hours. The prime minister insists precisely this time will be achieved.

Currently fast trains from East Midlands Parkway to Sheffield – a distance of 44 miles – are scheduled to take 40 minutes.

The link from London to Leeds via HS2E was scheduled to take 81 minutes, saving 39 per cent on the current journey time of 133 minutes.

Mr Johnson said: “We’ll look at how to get HS2 to Leeds too, with a new study on the best way to make it happen.”

Between Birmingham and Leeds the saving was promised to be even more – cutting the current 117-minute journey to just 46 minutes, saving 61 per cent.

What about HS3?

This was the proposed high-speed link across the Pennines between Manchester and Leeds – known fairly interchangeably as HS3 and Northern Powerhouse Rail.

The core line and additional projects would vastly increase capacity and speed on the trans-Pennine links from the Mersey to the Humber and the Tyne.

The 2019 Conservative manifesto promised: “We will build Northern Powerhouse Rail between Leeds and Manchester and then focus on Liverpool, Tees Valley, Hull, Sheffield and Newcastle.“

Journey times as short as 20 minutes have been floated between Leeds and Manchester, two of the biggest cities in northern England, compared with the current fastest trip of 50 minutes.

In July 2019, Boris Johnson pledged: “I want to be the prime minister who does, with Northern Powerhouse Rail, what we did for Crossrail in London.”

This is a reference to the £19bn rail link across the capital that connects Reading and Heathrow with south Essex and southeast London, though not at high speed. It is currently running four years late and well over budget.

“Today I am going to deliver on my commitment to that vision with a pledge to fund the Leeds to Manchester route,” Mr Johnson continued.

“It’s going to be up to local people to decide what comes next. As far as I’m concerned that’s just the beginning to our commitments and our investments. We want to see this whole thing done.

“I’ve asked officials to accelerate their work on these plans so that we are ready to do a deal in the autumn.

“Feel free to applaud.”

So that’s all clear, then. When can I step aboard?

The first passenger HS2 trains may run between London and Birmingham in 2029 – though probably from a suburban station in west London, Old Oak Common, as the intended hub, Euston, will not be ready. The links to Crewe and Manchester will follow in the 2030s.

It is now clear, though, that Northern Powerhouse Rail, along with most of the eastern leg of HS2, has been scrapped.

As The Independent reported, it will be replaced by some small-scale improvements.

But I read that rail travellers should rejoice?

The government says: “Faster train journeys will be delivered up to 10 years sooner under the government’s new Integrated Rail Plan (IRP), with biggest ever £96bn investment in the rail network.

“From London and across the Pennines, the IRP delivers journey times which are the same as, similar to or faster than the original HS2 and Leeds-Manchester proposals, while doubling or trebling capacity and ensuring passengers and consumers benefit from tangible changes more quickly.”

Ministers say the new plan is “delivering the same ambition for better value for money for the British taxpayer”.

Do rail experts agree?

No. Nigel Harris, editor of Rail magazine and the foremost commentator on the railway industry, told The Independent: “If you don’t do HS2E there’s almost no point in doing HS2W if all it is to be is a bypass for the West Coast main line.

“The biggest benefits will have been sacrificed in the name of political spinelessness and chronic Treasury short termism: knowing the cost of everything and the value of nothing.”

Lilian Greenwood, the Labour MP who is the former chair of the Transport Select Committee, said: “If ‘HS2 trains will instead be directed on to existing track for much of the journey to Yorkshire’, then surely instead of adding loads of new capacity, it will make things worse rather than better?”

Surely speed isn’t everything?

Correct. The aim of HS2 is to relieve the capacity crunch on the Victorian rail network, by moving inter-city services off the creaking 19th-century infrastructure. Speed is just a welcome by-product. Removing passenger expresses will dramatically increase options for local and regional trains, as well as freight – with people and goods coaxed from road to rail.

Almost halving the journey time between London and Birmingham to 45 minutes is a bonus; a completely new line in a highly congested nation might as well be designed to operate at 225mph to match the best in Continental Europe.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments