Forget Interrail - How Eurail really paved the way for border-free European train travel

Many travellers imagine Interrail was the first European unlimited rail pass. In fact, the idea was born in America in the Fifties

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Amid a galaxy of travel anniversaries in 2019, from British Airways’ centenary to the half-century since Concorde first flew, there’s one which has barely warranted a mention. It was 60 years ago that the first Eurail passes were sold. And without the growing success of Eurail in the 1960s and the launch in 1971 of a Eurail pass for students visiting Europe from overseas, it's very likely that the great travel icon, Interrail, would never have been created.

The credit for getting Eurail launched must go largely to an unassuming Frenchman called Pierre Le Bris. From his base in San Francisco, he worked closely with the French national rail operator SNCF and the US-based Rail Europe agency. Le Bris realised the difficulties that Americans visiting Europe had in booking train tickets in advance. His canny idea was to liberate these visitors by letting them use a rail pass which afforded a real freedom to roam.

Rail Europe Inc sold the first Eurail passes in 1959. Before long the company was very purposefully shaping itineraries that showcased European cities and landscapes. The firm helped to create in the American imagination an idealised view of a Europe which swept from Paris through the Rhineland, the Alps and the Riviera to northern Italy.

In the early days, Eurail was an unashamedly upmarket product. The rail pass was geared mainly at leisured North Americans who wanted first-class travel on posh trains that boasted amenities such as silver-service dining and even, on occasions, an on-board hairdressing salon.

A few months before the first Eurail pass was issued, the Boeing 707 entered service – and the new jet meant that transatlantic air travel became more comfortable and affordable. With air fares falling in the 1960s, there were demands to open up Eurail to a wider clientele. That came in 1971 with the launch of a modestly priced second-class pass for students and young travellers who wanted to roam the rails of Europe west of the Iron Curtain.

Again, it was restricted to travellers from outside Europe.

The post-1968 beat generation was on the move, guitars in hand, and they came in their thousands, keen to explore not merely the canonical sights that featured in the Rail Europe posters but also eager to take in places off the beaten path.

Young Europeans were quick to question the logic which underpinned Eurail.

“Why,” they asked, “should young Americans and other overseas visitors get a great value rail pass to explore Europe, while we who live here on the continent cannot benefit from this offer?”

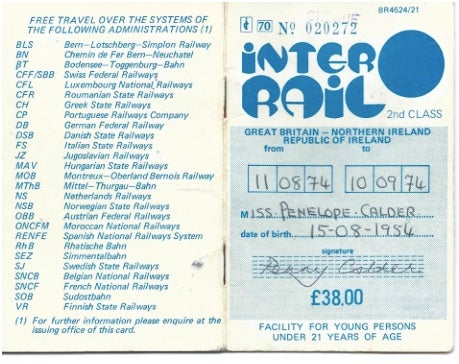

The pressure was on, and it was no surprise when in 1972 the national rail administrations of 21 countries launched Interrail: a product which was geared to European residents and actually covered an even larger area than Eurail.

Both schemes have gone from strength to strength. These days both Eurail and Interrail are administered by a single agency, based in the Netherlands, which ensures that broadly similar conditions apply to the two schemes.

In overseas markets, Rail Europe remains a major retailer of the Eurail pass and they, like other agencies, are keen to promote the idea that having a rail pass valid for one, two or even three months unlimited travel doesn't mean riding the rails endlessly.

Wise travellers are more inclined to opt for passes which allow five or seven days travel in a one-month period. And both Eurail and Interrail also offer passes which can be used for 10 or 15 days within a two-month spell.

Looking back at some of the early publicity for Eurail in its launch year, it's interesting that the focus was as much on the journey as the destination. Bavarian castles, snowy Alpine peaks and Riviera coastlines were things to be seen from the secluded comfort of a first-class seat. Europe was presented for its cinematic appeal.

The launch of Interrail in 1972 used other touchstones, placing less emphasis on scenery and landscapes, instead promoting the merits of engaging with young Europeans from other countries.

These days, the explorers who roam the railways of Europe with Interrail and Eurail are as likely to be pensioners as students. But, whatever their age, we hope they will spare a thought for Pierre Le Bris who first had the fine idea of creating a rail pass which would allow travellers to discover the joy of travelling on a whim.

Nicky Gardner and Susanne Kries are the authors of Europe by Rail: The Definitive Guide. The 16th edition of the book has just been published. Find out more at europebyrail.eu.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments