Everything you need to know about the Cape Town drought

Your questions answered about the approach of 'Day Zero'

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Could Cape Town be the first major city in the modern era to run out of drinking water? After three years of drought in the Western Cape province, that’s the fear for nearly four million citizens — and South Africa’s tourism industry. These are the key questions and answers for prospective visitors.

What’s happening?

Rainfall in Western Cape, where Cape Town is located, dwindled dramatically in the three years to 2017. Piotr Wolski, a researcher with the University of Cape Town’s Climate System Analysis Group, describes the spell as “very rare and severe”.

"My findings are that this kind of drought occurs once in 311 years," Dr Wolski wrote.

Reservoirs (known locally as “dams”) that feed the city have dwindled to around a quarter of normal levels, while plans for desalination plants are behind schedule.

“Day Zero,” when the reservoirs run dry and the supply of fresh water to taps is cut off, was originally calculated to be 21 April 2018. The estimate has now moved to 11 May. The city authorities warn: “The impact of Day Zero on the economy of Cape Town will be catastrophic.”

As Capetonians endure the stress of chronic water shortage, Jamie Bowden, a British tourist in the city, reports: “Plastic jerry cans and water butts have sold out across Cape Town, and supermarkets are restricting amount of bottled water people can buy.”

South Africans living outside Western Cape are being urged by charities to donate water to be taken to the province.

What’s being done?

As of 1 February the daily allowance per person has been lowered from 87 litres to 50 litres. The authorities say that just over half the population are adhering to the limit.

The tourist industry continues to function. South Africa Tourism says: “Cape Town and the Western Cape are open for business in spite of the current drought. Tourists will still be able to visit the region and access and enjoy primary tourism attractions such as Table Mountain, Cape Point and Kirstenbosch Botanical Gardens.

“In the event of what the City of Cape Town refers to as ‘Day Zero’, there will be available water for tourists’ and locals’ critical needs. These are considered to be water for personal hygiene and consumption.”

Hotels, bars and restaurants remain busy. Visitors are naturally expected to behave responsibly and do all they can to conserve fresh water, such as showering for no more than two minutes. Bars and restaurants have turned off the taps in their toilets, with customers asked to use hand sanitiser instead. Some hotel swimming pools have been converted to salt water.

Carl Morgan, who has just returned home to South Wales from Cape Town, said: “All the hotels/restaurants within the city are taking action, small steps to restrict water use. But as a tourist you wouldn’t notice these, so the tourist ‘experience’ isn’t ruined. All tourists are asked is to be sensible and not wasteful.”

Dr Wolski sums up the situation thus: “Day Zero is not threatening our lives. It’s threatening our lifestyles.”

It still doesn’t sound a great place for a holiday right now. Can I cancel my trip?

You won’t be able to cancel without penalty at present: airlines and tour operators are implementing their normal terms and conditions.

As circumstances change, so might the attitude of travel suppliers. Tour operators may, as a gesture of goodwill, permit package holidaymakers to select a different destination without penalty. But unless the Foreign Office warns against travel to Cape Town there is no obligation for them to do so. At present the official travel advice is simply: "Be mindful of water consumption and comply with local restrictions."

Flight-only travellers are in a weaker position than package holidaymakers. Were the Foreign Office to warn against travel to Cape Town, if an airline continues to fly to the city it can stick to the original contract — effectively saying: “Our flights are still operating; the fact that you don’t want to go isn’t our problem.”

In practice, if conditions in Cape Town deteriorate airlines may offer the chance to postpone a journey or switch destination. But the chances of getting a refund are slim.

I’m stuck with a plane ticket to Cape Town in the next couple of months. What can I salvage from my trip?

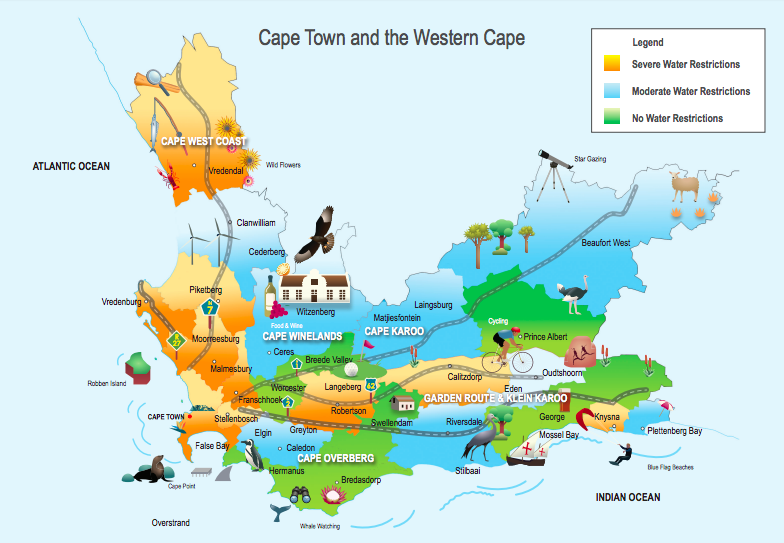

South Africa Tourism says: “There are still many places across the Western Cape that are not as severely affected by the drought such as the Garden Route and the Cape Overberg.”

Alternatively, fly on to another country. Neighbouring Namibia, to the north, has large swathes of desert and may seem in a state of perpetual drought. But with large-scale desalination already in place, drinking water is not a problem. Both Windhoek, the capital, and Walvis Bay (serving the adventure centre of Swakopmund), are a two-hour flight from Cape Town, and give access to the natural wonders of Etosha National Park.

If Day Zero were to arrive, for how long will the flow of water be cut?

Generally the winter rains in Cape Town start in April, but they can start as late as June. South Africa Tourism says: “We should be prepared to live with very little water for around three months, with the hope that by the end of winter, enough rain has fallen to switch the water system back on, but it all depends on when rain falls in the catchment areas that feed the dams.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments