The Independent's journalism is supported by our readers. When you purchase through links on our site, we may earn commission.

Can you repel mosquitoes with an app?

Developers claim that high-frequency sounds emitted from your device could keep the insects at bay

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.The menacing, high-pitched whine of a mosquito can instill an eerie sense of foreboding. Some mossies are just a pesky inconvenience, but in tropical regions they might be carrying sinister cargo onboard, such as malaria, dengue and now the Zika virus.

Of course, it shouldn't come as a surprise that there are apps designed to ward off mosquitoes. But to what extent do they actually protect you from being hunted down by these aggressive creatures?

Type the words "mosquito" and "repel" into Apple's app store or Android's Google Play, and dozens of apps will be listed, promising to thwart these hostile insects. The theory behind mosquito-repelling apps is straightforward: they're designed to make your phone emit a high pitched noise intended to mimic the sound of predators, such as dragonflies or male mosquitoes — noises that pregnant female mosquitoes steer clear of. (It's the impregnated female mosquitoes that bite — they have a penchant for fresh blood, while the males are busy binging on flower nectar).

The theory of mosquito-repelling apps may seem plausible, but are there any scientific studies to back up the claims in the blurb accompanying these apps? Requests to the developers of the seven most popular anti-mosquito apps, soliciting comment on the science underpinning these apps elicited no response whatsoever.

Fortunately, the medical community wasn't so reticent: Dr James G Logan, Senior Lecturer and Director of the Arthropod Control Product Test Centre at the London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine told The Independent that "there are studies that have shown that mosquitoes can communicate with wing beat frequency. But there are no studies that I am aware of that have looked at [mosquito-repelling] apps". And the consensus among the broader tropical medicine community about these anti-mosquito apps? "Since there is no data to support their use, these apps are not recommended" he says.

So what should travellers to mosquito-infected zones be doing to protect themselves from being bitten? Dr Logan suggests that travellers "should use a repellent that contains DEET 30-50% in high risk areas. PMD IR3535 and icaridin can be used on lower risk areas. Covering up with long sleeves and loose clothing is also a good idea. A bed net should be used particularly in areas with malaria".

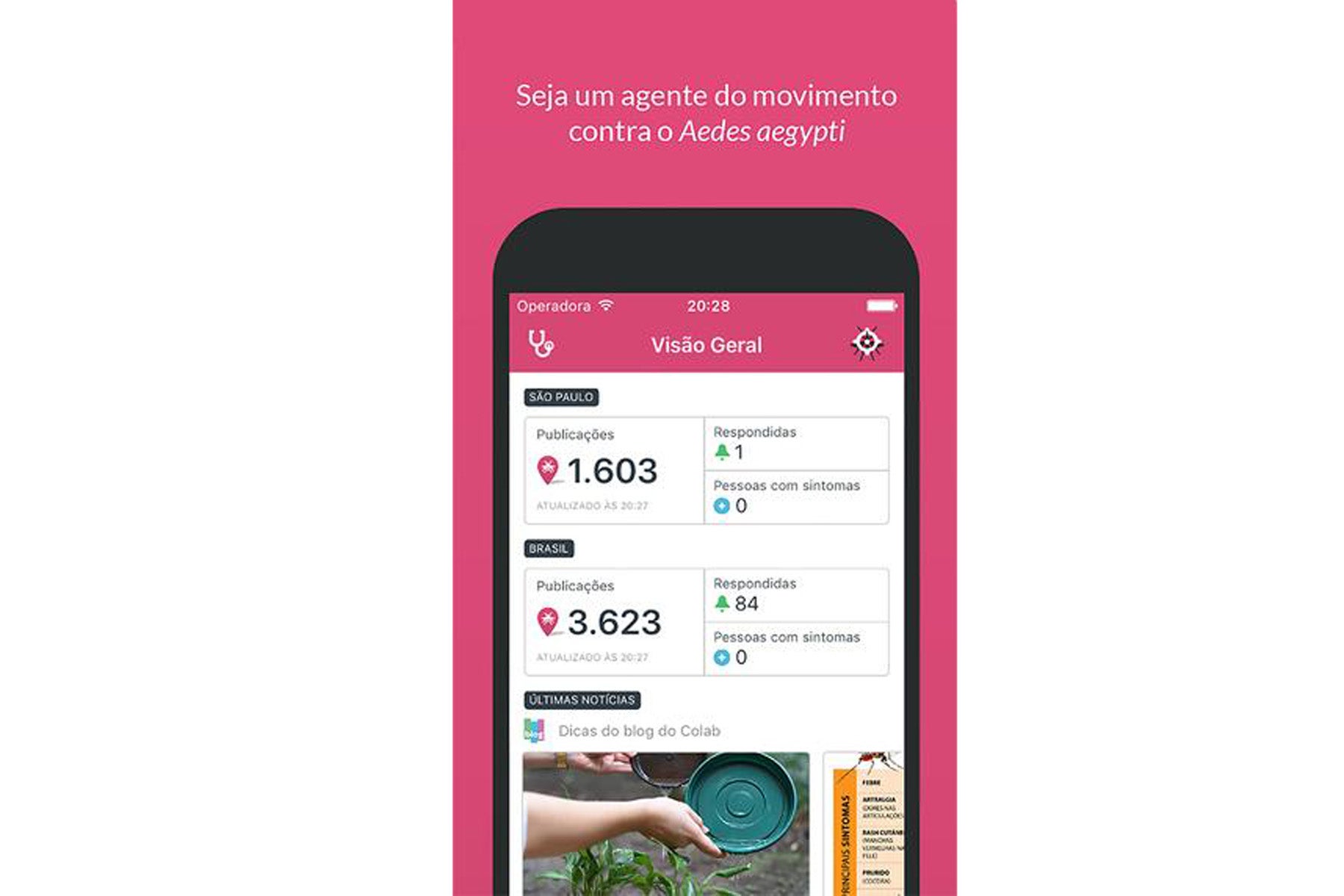

End of story? Not entirely. There is an app, available for iPhone and Android that can actually help in the fight against mosquito-transmitted diseases, but it's nothing like the apps that purportedly repel mosquitos from smartphones. Sem Dengue (“Without Dengue”) has been developed to enable anybody who spots mosquitoes or their larvae to take a snapshot which is tagged with geolocation data. Created by app developers Colab Tecnologia, the app has been introduced in Niteroi, a municipality of Rio de Janeiro, enabling local inhabitants to report sightings of mosquitoes via the app to the authorities which, in turn, can dispatch pest control teams to take appropriate action. Now the hunters become the hunted.

Paul Sillers is a freelance aero-industry writer focusing on design, technology, user-experience and brand strategy. He writes the “Future of Flight” column in BA's Business Life inflight magazine and contributes to Business Traveler USA, Raconteur, Quartz and Salt Magazine. @paulsillers

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments