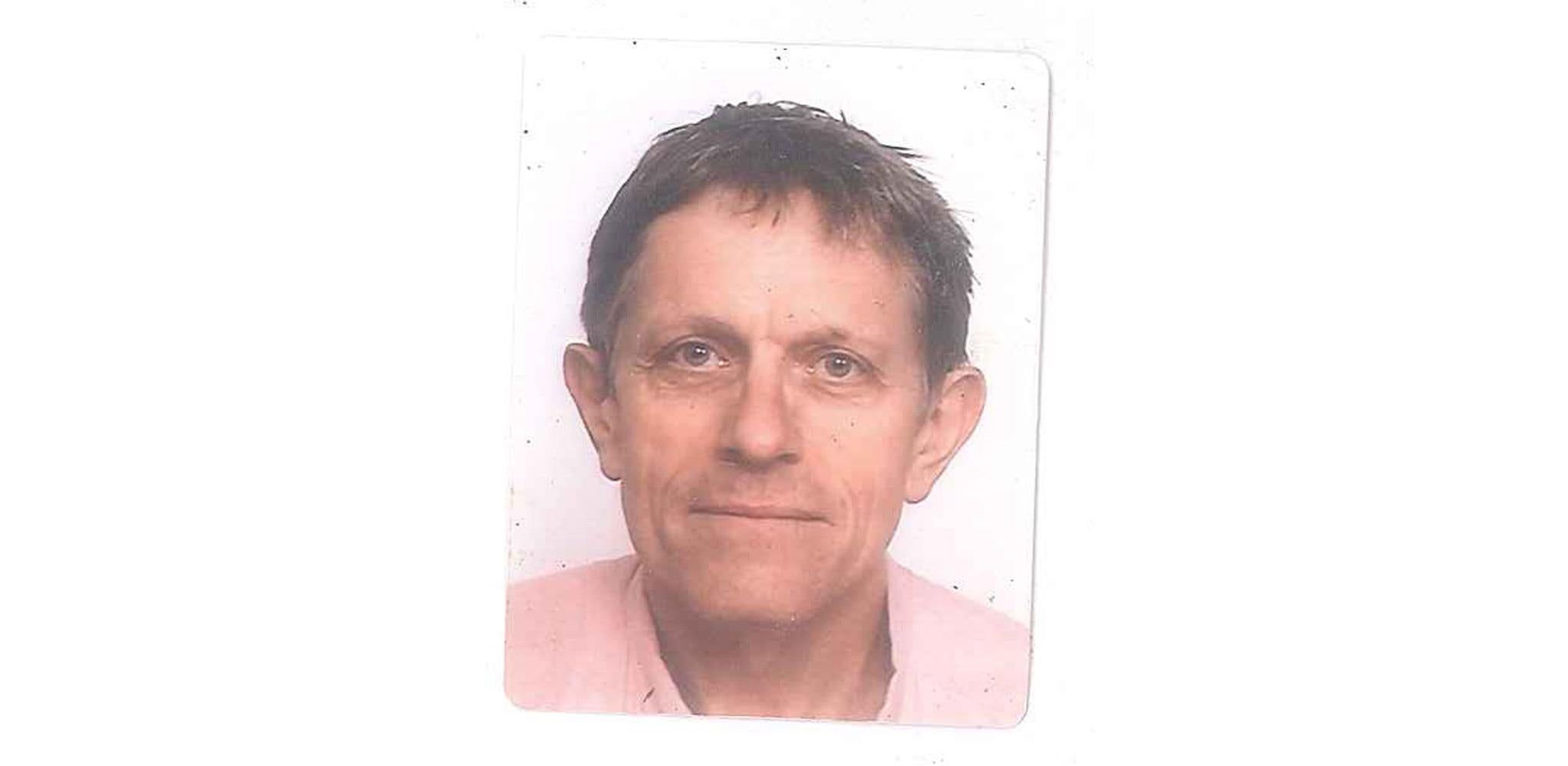

Why can't you smile in your passport photo? It's no laughing matter

Airport security is a serious business, says Simon Calder

Your support helps us to tell the story

This election is still a dead heat, according to most polls. In a fight with such wafer-thin margins, we need reporters on the ground talking to the people Trump and Harris are courting. Your support allows us to keep sending journalists to the story.

The Independent is trusted by 27 million Americans from across the entire political spectrum every month. Unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock you out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. But quality journalism must still be paid for.

Help us keep bring these critical stories to light. Your support makes all the difference.

“No smiling please, we’re French,” was one of many similar headlines on Friday, after a judge in France ruled that people must not grin on their photos for ID cards and passports.

Twelve years ago, the French were laughing on the other side of their faces when they gleefully reported the British decision to ban “open-mouthed smiles” from passport photos.

Mocking the surly expressions of the people on the other side of The Channel (or La Manche, if you are reading this in Paris) is good sport. But making fun of these legal stipulations diverts attention from the serious matter of biometrics – which affects the business traveller’s ability to move safely and smoothly around the world.

Your passport has a chip in it containing biometric information about you, derived from the photo you supplied when you applied for the document. That image was scanned, and key relationships (distance between the eyes, tip of the nose to the chin) used to generate a mathematical map.

Anything that distorts or disguises those measurements – such wearing sunglasses, or a broad smile – reduces the effectiveness of the algorithms used, rather like an out-of-focus photograph.

When you go through the e-gates at an airport, you look into a camera that scans your visage and does its own calculations. The computer then decides whether the mathematical map generated at Gatwick, Heathrow or wherever is a close enough match to the one stored on your passport.

After an overnight flight, and a long wait in the queue, you’re probably not feeling like smiling, which will probably help you speed through.

At the Airport Security 2016 conference at Heathrow this week, I learned a lot more about biometrics. The crucial measures are FAR and FRR, the “False Accept Rate” and "False Reject Rate”. National governments are very concerned about letting people pass through frontiers with someone else’s identification, and want machines to be sufficiently sceptical that only biologically identical twins might stand a chance. So they set the FAR bar high. But airports, airlines and all passengers want to the FRR score to be as low as possible, because that means few travellers have wearily had to abandon the attempt to get through the e-gates and instead go and smile politely at a real, live official.

Face recognition is also being increasingly deployed by law-enforcement agencies for the detection of suspected criminals, in particular people thought to have terrorist links. Technology exists that allows the output of CCTV cameras to be constantly checked against a data bank of “persons of interest”: if they are spotted entering an airport terminal or railway station, they can be challenged by police or security staff.

With the attacks at the airport terminals in Brussels and Istanbul fresh in the mind, business travellers may feel reassured – though as I have written in the past, the best way to reduce risk in the unprotected, “landside” areas of airports is to spend as little time as possible there: get to and through the security queue, pay extra if necessary for fast-track access, and trust that staff have done their job properly in maintaining a cordon sanitaire of the airside zone.

Staying safe is the most important factor, of course, but for many business travellers time is the next essential. And that’s where your hand may come in handy.

Before the September 11 attacks, the US authorities allowed “trusted travellers” from outside America to enter the country by placing their hand on a square marked out with pegs, using the analysis of hand geometry as a good biometric. These days it is not rated as secure enough, and iris recognition is the preferred measure. But many people are uncomfortable with having their eye checked out. Handily, there is a biometric that is regarded as just as effective: the pattern of veins in your hand.

While nothing will change imminently, within a decade you may be able to cross a frontier with a wave of your hand – and with a smile on your face.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments