Did you know when you fly to Dublin, you pass over Ginis? The secret codes of pilots and air traffic control

Pilots swear by these five-letter words - but as technology improves, could the secret language of aviation disappear?

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

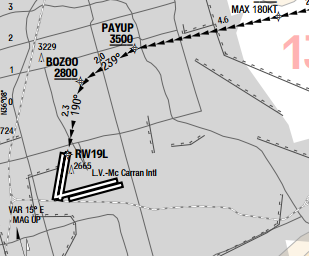

Your support makes all the difference.“Payup, Bozoo.”

Unless you are a pilot familiar with the northern approach to McCarran airport in Las Vegas, that may look like a mildly menacing request for settlement of a debt. In fact, Payup and Bozoo are the last two “waypoints” for the optimum arrival in Las Vegas when the desert wind is from the south.

Pilots swear by these five-letter words. A waypoint is a location on the Earth’s surface with a specific latitude and longitude. Traditionally they were the location for beacons: radio transmitters helping pilots to be certain of their whereabouts. But there is no need for any physical indication of a waypoint; they are marked on aeronautical charts and feature on flightplans. By international convention, their names must comprise five letters (which are capitalised on maps and flight plans) and be easily pronounceable by people whose mother tongue is not English.

You might imagine that they would be diligently decided by international committees; in fact, individual air-traffic providers come up with their own, being careful to avoid duplication that could cause confusion.

Daisy, for example, occurs once in the US (just south of Santa Barbara on the Pacific Coast) and in Australia (close to Townsville in Queensland); with 7,000 miles of separation, they are unlikely to be easily confused. David crops up three times, but again they are far apart in the US, Japan and Italy.

UK controllers have fun when they are coming up with names. Just off the north coast of Wales, you find Rolex — which, aviation legend has it, was awarded the name when air-traffic staff were given bonuses for moving offices. A short way west, on the usual track to Dublin, planes fly over Ginis roughly at the time when a lot of passengers on board are anticipating their first pint of stout.

Yet while waypoints such as those on the way into Las Vegas provide essential guidance for pilots, at higher altitudes they are on the wane.

Historically, the sky has been carved up into “airways” — invisible highways along which planes are permitted to fly at specified altitudes — with waypoints as the intersections. When fewer planes were flying, and navigation equipment was less accurate, asking pilots to fly over waypoints helped to increase safety.

But with technology constantly improving, and GPS navigation so reliable, increasingly pilots are able to set a direct course to the destination.

“At least that’s the theory,” says Captain Andy Thorington of Thomas Cook Airlines. He devotes a lot of his time to improving the efficiency of aviation, and a good way to do that is to reduce the distance travelled. That means flying the most direct route, taking into account en-route weather, rather than using the waypoints of old. It saves on fuel and reduces emissions.

But isn’t it risky to allow planes to fly in straight lines from A to B rather than along neat, waypoint-defined routes via Daisy or Ginis? Captain Thorington says no.

“If there are any potential conflicts they’re known about in the air-traffic world long before you get close to another aeroplane.”

So next time you are on board a Thomas Cook flight, pay attention to the pilot's briefing. He or she may get you to your destination quicker than anticipated.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments