Journey to Mecca: How it felt to visit the common link of an entire worldwide community

I felt an urge to spread my arms and embrace everyone, enfold every one in my exultation

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.The pilgrim bus was stuck in an almighty gridlock.

Through an early morning haze, I surveyed the snarled jumble extending for miles. The buses, the standard yellow American school bus variety, were distinguished by large Arabic and English lettering on their sides. Around each bus lapped a churning tide of white cloth draped over countless pilgrim souls. The only sign that this ocean contained individual forms came from the varying hues of human flesh. Male pilgrims all wear the same traditional dress – two pieces of unstitched cloth, known as ihram – in such a way that one shoulder is left bare. This vast seething mass of humanity, between two and three million people, is drawn from every corner of the world, all rushing at the one appointed time to this one place: Mecca.

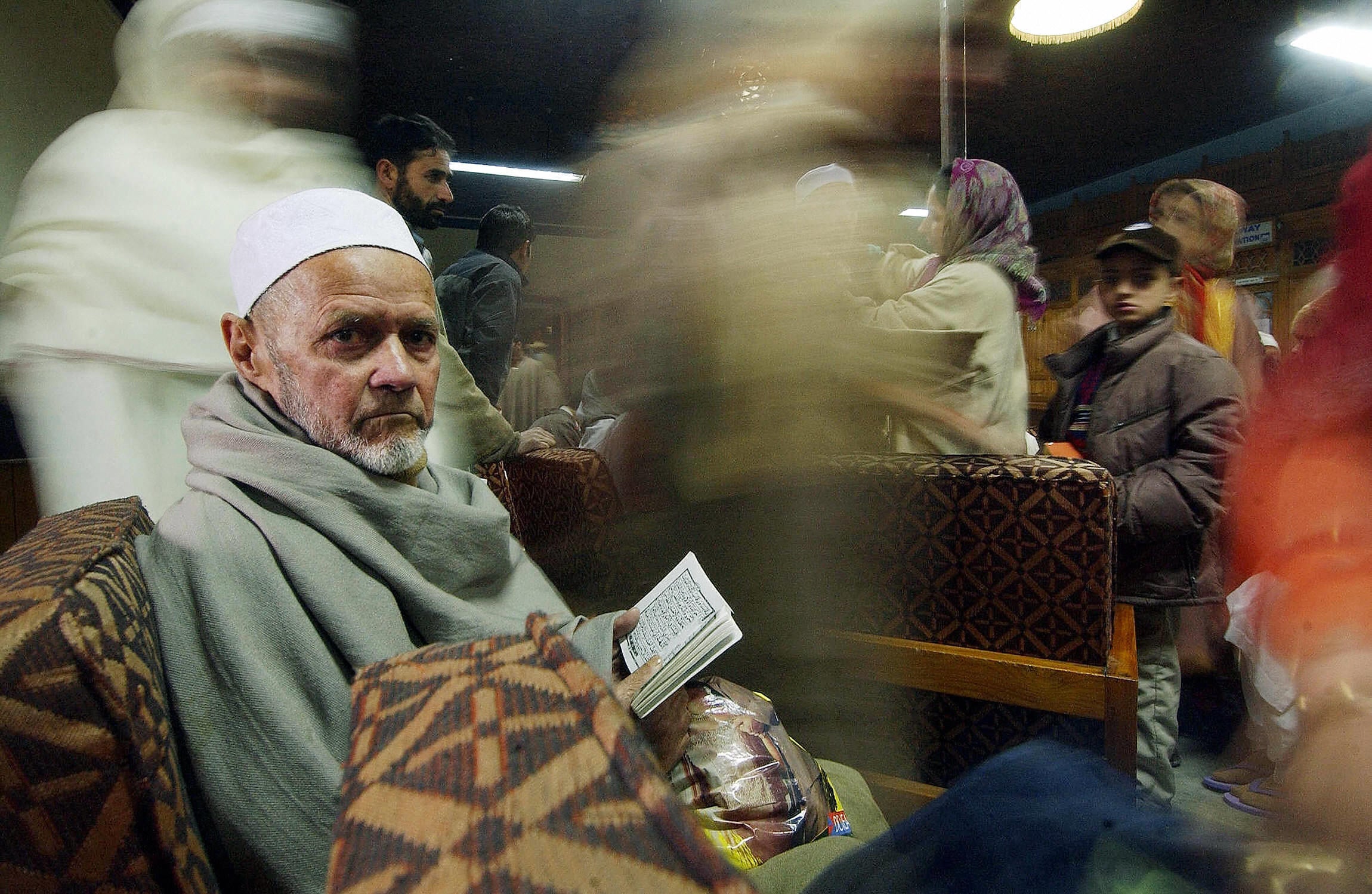

Once gathered, pilgrims move en masse around the city and its environs progressing from one sacred site to another. This particular tide was to take them from Muzdalifah, where they had spent a night under the stars, to Mina, some three miles away, where they would symbolically humiliate Satan by casting stones at three pillars of rock. But like some powerful bore attempting to force its way up a narrow channel, the onrush had backed up, a white-crested wave as yet unable to generate any hint of forward motion. From my vantage point, it was not the fluid dynamics of this impasse that fascinated me. The jostling stasis before me was becoming as traditional as the pilgrim garb has always been. Frequent congestive interruptions are modernity’s answer to manoeuvring multitudes of people from place to place by the most up-to-date means. Already, I found these hiatuses at odds with my exalted expectations and cherished ideas of the experience offered by this place at this time. Perhaps it was the detachment of ideal and reality that captured my mind. Perhaps it was something in the power of this place. As I surveyed the scene before me, I was drawn through the myriad host to just one bus and just one face.

The bus was stuck in a colossal traffic jam. Through one of its windows, I saw one pilgrim sitting perfectly still. A wrinkled face illumined by eyes whose gaze was focused beyond the horizon. Mesmerised by that look, I transported myself through the hubbub towards this old man. As I inveigled my way through the crush, I understood that he was aware of me, though his gaze had not shifted nor had he made any movement. Only when I got close to the bus did he move. With the deliberation of age and infinite effort he negotiated his way against the tide to leave the bus. It seemed to take for ever. I watched each tottering step until he stood before me. Face to face, I knew what had drawn me to this one old man. Serenity emanated, a blissful calm surrounded him. Without a word, he stretched out his hand and gave me the two pieces of bed linen he had been clutching. Instinctively, I took hold of his bundle and followed. He led me beyond the crowds.

At a quiet spot beyond the roadway, he indicated that I should lay his sheet upon the ground. It billowed like a sail in the morning breeze. When I had smoothed it out, he lowered his frail body onto it and settled himself down. I sat beside him – I don’t know for how long. We did not talk. There was nothing to say. And then I knew he had traversed the horizon. Gently, with reverence, I spread the second sheet to cover his body. Only then did I become concerned. What should I do next? What memorial, what procedure, who to tell, how to keep his body from being trampled by some sudden eddy of the crowd? I was left with questions. He had his answer, his final destination.

It was 16 December 1975. I was fulfilling one of the most important religious duties of a Muslim: Hajj, or pilgrimage, to the sacred city of Mecca. I was excited, enraptured, and somehow connected to more than two million other pilgrims who were performing the Hajj. I hoped to return spiritually uplifted. Yet the old man had come to die. I felt that he understood the inner meaning of Hajj better than me.

Mecca, birthplace of Islam and also of the Prophet Mohamed, is Islam’s holiest city. It is a city that I, in common with almost all Muslims, have known all my life. A once-in-a-lifetime visit to Mecca is a key obligation. Most Muslims, however, will never see Mecca, and yet will have learnt, perhaps even memorised, its geography from the moment they were taught to pray. The first lesson for any Muslim child preparing to pray is to identify the location of Mecca, and then to prostrate in the direction of the city, not once, but five times daily.

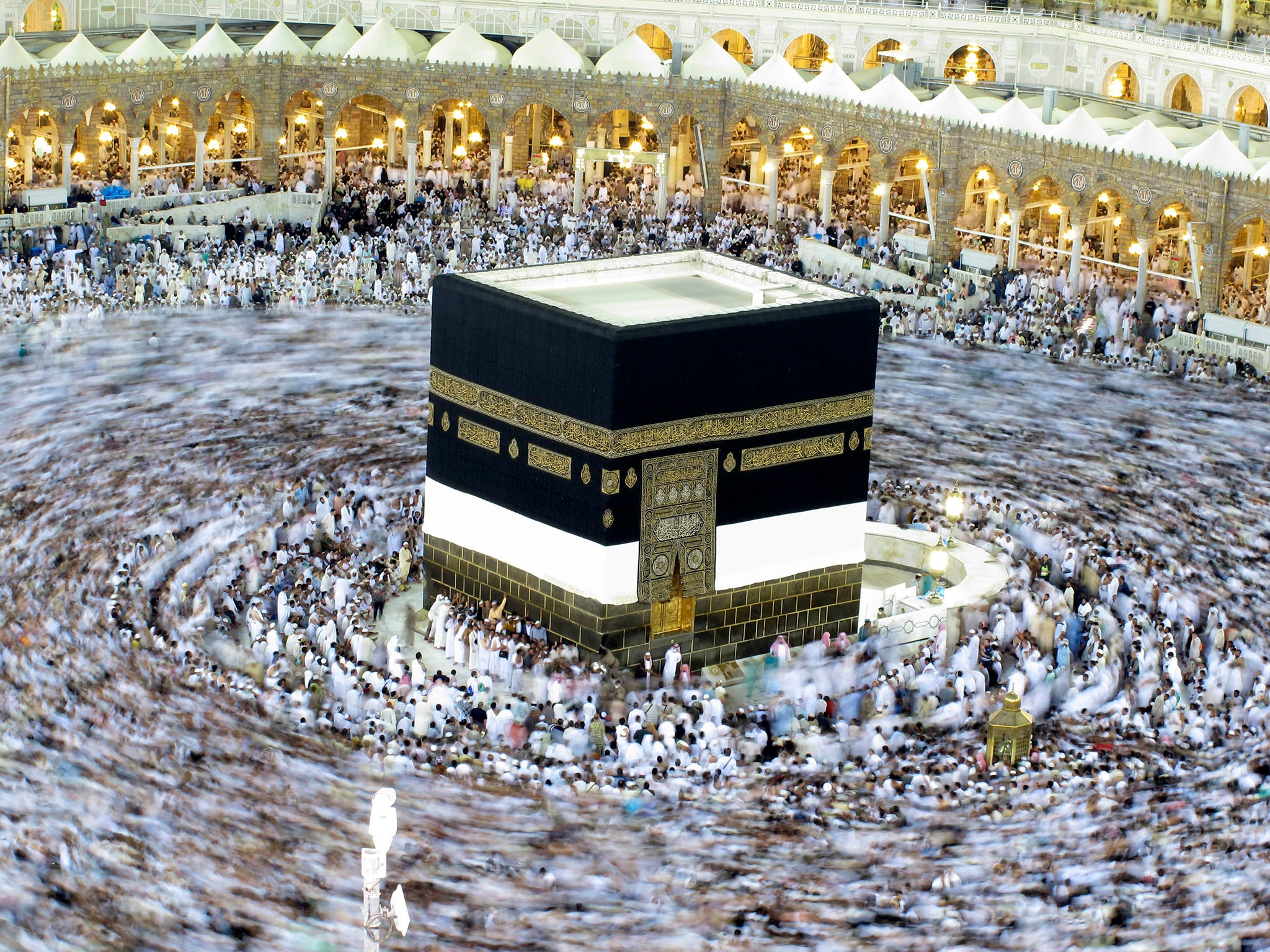

Our house in Dipalpur, Pakistan, where I was born and spent my infant years, had one tattered old calendar on the wall. The calendar had a picture – rather gaudy, I now realise – of the Sacred Mosque that stands at the heart of Mecca with its soaring minarets amid the encircling hills. The heart of the Mosque, the centre of the picture, was the Kaaba. The Kaaba drew the eye. It was an abrupt, arresting presence, a simple cuboid structure enveloped by a drapery of gold- embroidered black cloth. If you peered intently at the picture, you could just make out that the streams of white swirling around this focal point were a mass of pilgrims. The word “Allah” was written in bold Arabic letters just above the minarets.

Time has moved on, but the image of the Kaaba on our decorative calendar is fixed, burnt into my memory. The very first picture I ever saw confirmed in me the certain knowledge that, while God is everywhere, in some special sense the divine power is focused in this one place; that the Kaaba is quite simply God’s House. This picture so clearly indicating God’s presence formed a primal bond that I knew connected me, inseparably, for all time to this one place. It was a childish innocence, and yet everything I learnt was to strengthen this conviction. It grew up within me as I added new layers of understanding. This sense of personal attachment is not mine alone. It is a love and devotion, a yearning and a dream that I share with more than a billion others. It is a common bond between Muslims: Mecca and I is at one and the same time Mecca for all. To be at Mecca is the taproot of individual identity and the common link of an entire worldwide community.

My first religious lessons were all about Mecca. When my mother taught me to read the Koran as an infant, I learned that the Sacred Text of Islam was God’s Words first revealed to Mohamed at Mecca. The stories I was told about the life of the Prophet Mohamed made Mecca and its environs more familiar to me than the country in which I lived: the cave at Hira, on the outskirts of Mecca, where the Prophet received his first revelations in 611; the town of Medina, which was called Yathrib during the days of Mohamed, where the Prophet sought refuge from persecution in Mecca; and the well of Badr and the mountain of Uhad where the Prophet fought his battles. But in Islamic tradition the history of Mecca long predates the 7th century. The holy precincts around the Kaaba contain stories stretching back to the very beginning of time. Adam, who in Muslim tradition is the first Prophet, visited Mecca and was buried there. Prophet Ibrahim, or Abraham, the father of monotheistic faiths, built the Kaaba with his son Ismail, or Ishmael. Every Muslim child grows up with these stories, internalising their geography as a personal landscape whose contours and history define who they are.

But Mecca is so much more than a place where things happened once upon a time in history. Mecca matters because, as my mother often explained, it was there that God revealed to the Prophet Mohamed his guidance on how to lead a moral life. So what the Prophet taught, what he said and how he did things provided the examples that I was told I should try hard to follow in order to grow up to be a fine human being. What happened in Mecca was alive in the simplest daily activities of my life, in all the strictures with which adults seek to tame youthful exuberance and the knotty deliberations that a gregarious youngster like me encountered in determining whether I was being naughty or not so nice. There was never a doubt that I must always look towards Mecca if I was to amount to anything worthwhile in this world.

When I was sent to more formal religious lessons, the supple sympathy of my mother’s approach was replaced by the sterner discipline of the madrassa. The lessons I was required to master fed my fascination with Mecca. I learnt that one of the five pillars of our faith was an obligation to visit Mecca, if I was able, at least once in my lifetime to perform the Hajj, to be part of the great annual pilgrimage that is the highest expression of Muslim existence. I drank in all the details: one had to walk around the Kaaba – for real. The other stations of the pilgrimage became landmarks in my growing sense of geography. What an adventure it would be – to cross continents and stand where the Prophet had stood, to walk in his footsteps performing the same rituals he established and be part of that ocean of brotherhood that united people of every race and nation. And ultimately to stand with this vast gathering to ask God directly for His mercy and blessing – of course I was determined, like Muslims everywhere, that one day I would go to Mecca. I would be a pilgrim, Mecca would not always be a picture: one day I really would be there.

My family did cross continents, though we bypassed Mecca as we journeyed from Pakistan to settle in London. We changed the course of our lives in many ways – but Mecca remained a fixed point. We had, of course, to locate it from a new direction, but it was still central to our shifting identity. Our new home raised complex new questions, from the existential to the utterly practical, in which Mecca was a vital feature of the choices we made. As I grew up in London, Mecca continued to be my lodestone and objective. And then, as I dreamt about Mecca and planned to visit the city during my mid-twenties, Mecca actually came to me. It came as an offer of the job of a lifetime. This was to become part of the team at the newly established Hajj Research Centre, based in Saudi Arabia’s port city of Jeddah. The centre was located on the campus of the newly established King Abdul Aziz University, and my job was to study and research the logistic problems of Hajj, as well as the past, present and future of Mecca.

I worked at the Hajj Research Centre for five years. I took part in the Hajj itself for each of those five years, studying the comings and goings of Hajj pilgrims, and also those who would come for the year-round “lesser” pilgrimage that is known as Umra. The rituals of Umra are a subset of the Hajj and can be performed at any time of year outside the designated Hajj season, which falls in the 12th and final month of Islam’s lunar calendar. During those years, I became intimately familiar with Mecca and its environs, I watched them change, almost never according to the ground plans and advice we devised at the centre. In those years, and since, I have travelled to and from Mecca many times, by various means to and from many places in the world. And still nothing quite prepares you for the experience. Nor is there anything I can compare to the very first time I entered the city of my heart’s longing and found myself within the Sacred Mosque.

It was late afternoon. I went through the main gate, Bab al-Malik. I began to tremble as I walked through the cool shaded building upheld by innumerable archways and approached the final colonnade. The light beyond the shade rebuffed me. It was not daylight. It was some intensified glorious glow, a luminosity peculiar to this place, contained within the open plaza at the heart of the Mosque. The oxygen drained from my lungs. “I am here.” The thought reverberated through my body with each gulp for air. “I am here.” The words struggled to emerge from my open mouth.

My head was spinning, yet my eyes were focused on the Kaaba. I stood in awe and wonder, reverence and astonishment, elation and perplexity; a profound sadness and an irresistible smile of infinite joy took possession of me simultaneously in a moment that seemed to last for ever.

I felt an urge to spread my arms and embrace everyone, enfold every one in my exultation. And yet I was blissfully unaware of other people here in this place. It was me and the Kaaba. How could it be here? How can I be here? How can it be here before me? It was beyond imagination, beyond comprehension, more than reality. It was the point at which there is only prayer.

This is an edited extract of ‘Mecca: The Sacred City’, by Ziauddin Sardar (Bloomsbury, £25), which is published today

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments