Inside Ushguli, the most remote village in Georgia

Settlement has been abandoned by many of its residents, but new flights are bringing in tourists and are giving community new lease of life

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Georgia’s on everyone’s minds, at the moment. With Tbilisi reigning as the hot ‘new’ city break, thanks to direct flights which launched last year and new flights from Luton to Kutaisi opening up the north of the country, it feels like everyone is going.

One place they aren’t going, though, is to Svaneti, in the far, mountainous north of the country and in particular, to the four villages that make up Ushguli, one of the region’s most remote outposts and Europe’s highest permanent settlement.

Tough and taciturn, speaking an archaic Georgian dialect and practising a version of Orthodox Christianity owing much to earlier beliefs, Svan cultural identity is distinct. Isolated by an annual six-month winter, until the early 2000s Svaneti remained a lawless place; blood feuds and banditry were widespread. Georgians even ridicule Svans as unsophisticated (although, sensibly, they do it quietly).

Stymied by its remote location, Ushguli had long endured a terminal decline, as harsh conditions combined with instability to drive depopulation. However, as Georgia has emerged from post-Soviet chaos, security has returned to Georgia, including Svaneti.

Once the country’s most dangerous road, the route to regional capital Mestia has now been upgraded. It’s still a journey approaching five hours from Kutaisi, but with the new flights, it’s at least possible to visit.

In Zhibiani, one of the larger villages, ancient Svan defensive towers overlook the winding lanes and wandering livestock. Substantial stone buildings of two storeys, upper floors fronted by enclosed wooden balconies, lie in varying states of repair.

Marekhi Nijharadze’s house is in good order though, with Soviet symbols recalled in decorative fretwork. She invites Alex, my Georgian guide and me inside.

“I came here as a midwife,” she laughs. “Life was very different in the 1950s. I was the only medic. I had to extract teeth and even perform small surgeries. There was no money, no transport and the road to Mestia was terrible. It wasn’t what I was expecting but I wanted to help.”

These days Marekhi runs a guesthouse; beds stand wherever there’s space, while an extension to make room for more is clearly underway. In an original bedroom two significant fissures track across the wall – scars from the 1987 avalanche which saw half Zhibiani’s residents pack up and leave.

“Just 50 people remained – everyone was trying to escape,” she says. “Finally, tourism has brought them back.”

Despite its rough and ready nature, for centuries Svaneti proved a safe and remote repository for art and learning, usually under the protection of Orthodox monasteries. On a hill overlooking Zhibiani, against the backdrop of Shkhara’s snowy 5,000m massif, Lammeria monastery remains home of the Bishop of Upper Svaneti.

Past a shepherd dog the size of a pony is the entrance, where a bearded and robed monk appears and rings a peel of three bells. He opens the door to a tiny 10th century chapel and motions us to enter, lighting a candle before we take a seat.

“I was supposed to come for a month,” he says.

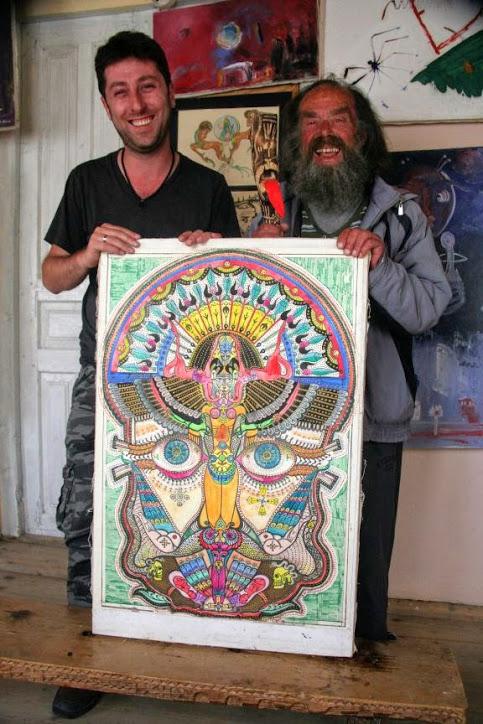

Not everyone in Ushguli is so straightforward. Surrealist artist Pridon Nijharadze also lives in Zhibiani, leading a reclusive existence and giving few interviews. He’s rumoured to be an awkward and eccentric character; but Alex knows Pridon’s nephew, who’s willing to make an introduction.

We walk along narrow alleys, past abandoned Russian trucks and silently wandering cows, to a half-stone, half-wooden building. At the top of a flight of steps, a whiskered elderly man eyes our approach – Pridon, as it turns out. “What do you think of the positions held by Stalin and Roosevelt after the Tehran Conference?” he demands by way of introduction. Happy with Alex’s reply, he invites us into his studio, to tell us about his past. “In the 1970s I studied in Tbilisi, but they couldn’t give me anything,” he says. “What I wanted to paint wasn’t allowed.”

“I demonstrated against the Soviets when they banned the Georgian language. They put me in an asylum, took my blood, gave me drugs. I’ve had health problems ever since.”

Little by little Pridon opens more doors, allowing us further into his studio’s inner sanctum. “This,” he says, pointing at a brooding canvas detailing multiple Svan towers, “is the Tower of Babel”. He interprets other references for us – scissors are actually a woman’s legs. Pridon’s art has always been designed to provoke.

I ask the source of his inspiration: “It comes from the cosmos,” he replies without a moment’s hesitation.

As we take our leave, Pridon tells me more about the impact of new prosperity on Ushguli. “It’s like a resurrection,” he says and picks up a particularly psychedelic canvas. “This, it’s special. I painted it in 1999 and if it sells I’ll give the money to the people of Ushguli – those who stayed through the winters.”

I’m sure his asking price will be reasonable.

Travel essentials

Getting there

Wizz Air flies direct from Luton to Kutaisi from £50 return.

Staying there

Nick Redmayne travelled with TravelLocal (0117 325 7898; travellocal.com), which hooks users up with local tour operators. A Long Weekend in Svaneti tour costs from £510pp excluding flights.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments