The great fly past: why you should visit Malaga

This city is our gateway to the Costa del Sol, yet few of us explore beyond its airport. We're missing out.

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Until now, I had no more thought of visiting Malaga than I might consider booking a holiday in Hounslow or Crawley. For most of us, Malaga is an airport – a necessary hurdle to be endured before hitting the heaving beaches of the Costa del Sol, or taking the high road inland for the gentler pleasures of the "white towns" of Ronda. That Malaga could be an end in itself seems perverse. Or plain lazy.

The first impressions are not encouraging. The signage off the road from the airport promises Centro Ciudad but leads me to a hangar-like sports centre surrounded by a series of lifeless housing estates. I appear to have fetched up in a system-built suburb of Warsaw. The roads are being dug up and the approach into town is a mess.

Eventually, I find the seafront, but as I drive deeper into the conurbation my heart sinks. Malaga's port is neither a picturesque fishing village nor a glitzy mooring for super yachts à la Puerto Banus. An ambitious plan to redevelop the port area is under way, but currently it has all the charm of a container terminal, which it is.

As I check in to the cool comfort of the Hotel Molina Lario, I have a few twitches about whether there is enough in this town to engage a casual visitor for a weekend. It is Friday afternoon and the hours before Monday suddenly seem a long slog.

Redemption arrives in the shape of my friend Pedro who lives in Marbella but has adopted the role of cheerleader in chief for his beloved Malaga. We leave the hotel and stroll around the pedestrianised centre of town. The embrace of Spanish street life is an immediate restorative. The sun is dwindling in the October evening but the air is still warm. Malagueños are out in force, eating, drinking, shopping and promenading.

We cross the cosy Plaza de Obispo which counterpoints the grandiose baroque frontage of the cathedral. The church was started in the 16th century and is visibly unfinished; the south tower of the façade is topped by the stumps of neo-classical pillars that appear to have been axed just below the knees by a celestial lumberjack. I learn that the money to finish the tower was given away by a bishop to help finance the fight against the British during the American War of Independence. Consequently, only a single finished tower graces the lopsided cathedral, which is known as La Manquita (the one-armed woman).

There is a limit to how many such cultural titbits I can absorb before my first taste of iberico. The exquisite ham is a part of my arrival ritual – Spain starts only when I have a ració*of jamon iberico de bellota and a cold cana (small beer from the tap) in front of me. Pedro leads the way through a jumble of alleyways of ever decreasing girth until we stumble into a promising looking hole in the wall. In Britain, La Bodeguilla would be an old gits' den in a forgotten back street. The bar lacks all pretension and is the perfect smoke-wreathed venue for jamon connoisseurship.

The counter is loaded with bottles of fino (dry white sherry), anchovies, bacalao and olive oil; the cold cabinet groans with morcilla and iberico lomo. Pedro asks if they are for sale. "Everything is for sale," quips the barman, "even me if the price is right." A generous portion of glistening iberico arrives accompanied by my beer and a glass of tinto de verano (cold, red wine, sugar and soda served from the tap) for Pedro. The first sliver of the acorn-fed ham on my tongue is an affirmation. Delicate, salty-sweet, smoky and succulent. I have arrived.

At 11pm we move on and the night can officially begin. It is an epic undertaking and needs to be carefully paced. At Pepa y Pepe we consume white wine and deep-fried octopus and acquire Carlos (one of Pedro's numberless cousins) and Gonzalo. At Bodega El Pimpi, we try the sweet moscatel. The walls are lined with barrels signed by the celebrity clientele, among them local hero Antonio Banderas and a very young Tony Blair – all sticky-out ears and bashful grin. The warren of bars and courtyards looks very Andalucian to me, but Gonzalo is withering: "This place is for tourists." It is out of season now, however, and the only language I can hear has the earthy accent of local Spanish.

By 2.30am we have lurched in and out of at least two other bars and a club; it is still warm enough for shirt sleeves. The centre is heaving; the crowds seem to be reaching a critical mass. We follow the echoes of chatter in the narrow, stone-lined streets. There must be 500 bodies spilling into Plaza Mitjana from the tiny bar Tita Conchi. The decibel count is ear splitting, like a flock of particularly garrulous starlings settling to roost. There is no DJ, no ramped-up sound system, no thumping beat – only happy talk and laughter. It is the music of people enjoying each other.

The city centre is buzzing for many hours yet – with partying Malagueños seemingly intent on wringing every last drop of pleasure from the moment. Malaga's lust for life also coursed through the veins of its most celebrated son, Pablo Picasso. "Each second we live is a new and unique moment of the universe," said the artist, "a moment that will never be again." He was only 10 when he left the city of his birth, but that has not stopped Malaga from claiming him. Picasso's birthplace, at Plaza de la Merced 15, is now a modest museum, but the real draw is the Museo Picasso which opened five years ago.

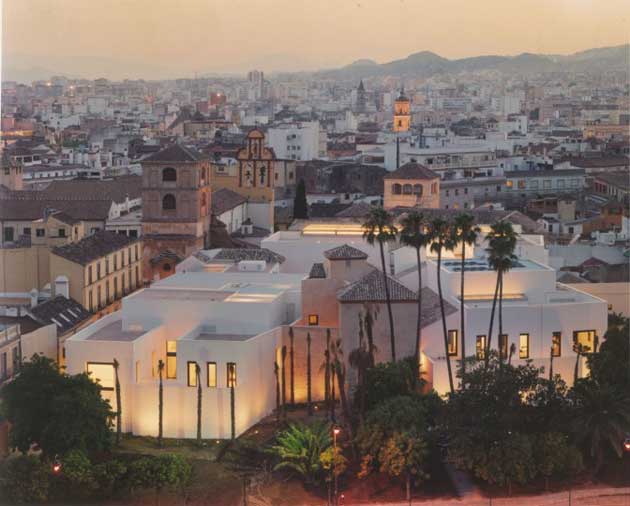

Compared with the big gun Picasso museums of Paris and Barcelona, Malaga's is a bit of a boutique. The collection includes familiar Cubist sketches, mashed-up portraits of various muses, perspective-bending sculptures and playful ceramics. But among the works donated or lent by Christine and Bernard Ruiz-Picasso (daughter-in-law and grandson) there are also some that seem particularly intimate and revelatory. The blank gaze of Picasso's son in Portrait of Paulo with a White Cap (1923) is haunting. It is a simple painting, a mere 10in by 8in, but the two-year-old's thoughts remain utterly opaque. He occupies his own universe – neither happy nor sad. Here, rendered in a few bold strokes is a sensation familiar to any parent.

Lunch is in El Palo, a fishing village which has long been subsumed into the sprawl east of Malaga. The density of parked cars as we approach warns of the restaurant's popularity. El Tintero occupies a vast covered terrace running along the seafront promenade; the trestle tables are packed with parties of friends and elongated families; waiters pass between them shouting at the top of their lungs. Plates of freshly fried seafood and jugs of wine are slammed down without ceremony; the percussion of cutlery adds to the atonal symphony. They describe this as a "fish auction", though the only similarity to an auction is the furious cacophony being generated. This is situationist eating. Anarchy in the gastrodome. Waiters bring whatever is freshly despatched from the kitchen, shouting out the name of the dish they bear. The almejas (clams) are fragrant with garlic, the boquerones (deep-fried fresh anchovies) and the calamares are meltingly soft. The "bill" is a screaming raucous bargain at about €15 each.

The road back to the city centre is overlooked by the ramparts of Gibralfaro. Though inevitably it suffers by comparison with the Moorish star turns of Granada and Cordoba, Malaga has its share of Muslim treasures. The hilltop fortress of Gibralfaro is thoroughly impressive in its own right. Originally built in the eighth century, it was substantially rebuilt in the 14th and 15th centuries. From the commanding heights of the fort's walkways Malaga is displayed in the backlight of the setting sun. The shoreline sweeps away both east and west to opposing vanishing points. The emirs who once commanded this coast had an eye for a view.

The solitary spire of the cathedral has a smoky halo; beneath it the severe white walls of the Museo Picasso are softened by palm trees. Down there 2,000 years of history are layered into the modern city. Following the walls down the ridge, I have a guilty pang when I spot the yet to be visited 11th-century Alcazaba palace. It was on my list of to-do sites, as was the recently excavated Roman amphitheatre next door. I can see planes rising soundlessly from the distant airport. I am out of time. And then it dawns on me. I have to come back.

Compact facts

How to get there

Sankha Guha travelled to Malaga as a guest of the Spanish Tourist Office (020-7486 8077; spain.info/uk). He flew with Monarch (08700 40 50 40; flymonarch.co.uk), which offers return flights from Birmingham, Gatwick, Luton and Manchester from £77 return. He stayed at the Hotel Gallery Molina Lario (00 34 952 06 2002; hotelmolinalario.com), which offers double rooms from £80 per night room only. Car hire was provided by Holiday Autos (08704 00 00 10; holidayautos .co.uk), which offers rental from £69 per week.

Further information

La Bodeguilla, Plaza de la Constitucion 11; Pepa y Pepe, Calle Caldereria 9; Bodega El Pimpi, Calle Granada 62; Bar Tita Conchi, Plaza Mitjana, 6; El Tintero, La Playa del Dedo, El Palo.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments