The Independent's journalism is supported by our readers. When you purchase through links on our site, we may earn commission.

Stalin Museum: The creepy attraction in Georgia that still worships the communist leader like a god

Nearly 65 years after his death, the Stalin Museum in Gori acts as a shrine to the Russian dictator

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.“Stalin. Very good poet,” our guide declares in a monotone, hooded eyes a testament to post-Soviet apathy. “Also, beautiful singing voice.” She stands beneath an array of surprisingly handsome portraits of the former dictator at a young age – a hipster dreamboat beneath his bouffant and manicured moustache, the display would have you believe – while members of our group shift uneasily.

Forget about gulags and purges: in the Stalin Museum in Gori, Georgia, staff wax poetic on the dictator’s Butch Cassidy-like exploits as a bank robber, Count of Monte Cristo-esque escaping abilities (“five times he escape Siberia,” our guide boasts) as well as his fabled artistry.

First opened in 1957, the museum complex sits beside the house in which Joseph Stalin was born in 1878 (when Georgia was a part of the Russian Empire). It has deftly resisted de-Stalinisation – the removal of Stalin’s name and effigy from public spaces following his death in a bid to curb his cult of personality – as well as more recent Georgia-led campaigns to convert the facility into a museum on repression. To this day, it remains a shrine to the sanguinary bureaucrat.

“The Stalin Museum is most certainly most authentic in terms of the Soviet-era feel captured by the decor, the installations and the general ambience created by the staff that are not only passionate about the subject, but in a way, also in awe of the man,” says Tinatin Japaridze, a native Georgian researching the country’s post-Soviet identity at Columbia University.

The whole effect is indeed Church of Stalin-like: upon entering the facility, a plush red carpet set atop a marble staircase leads you to an imposing statue of the Soviet ruler (not built to scale: Stalin clocked in at a mere 165cm, compelling former US President Harry Truman to call him “a little squirt”) standing beneath a stained-glass window. Visitors are invited to make their way through a series of spacious rooms containing encased memorabilia (including Stalin’s last pack of cigarettes and favourite winter coat) and a slew of paintings featuring the Soviet premier lifting children in his arms or declaiming before rapt committee members (a likely exaggeration: historians agree his oratory skills were limited).

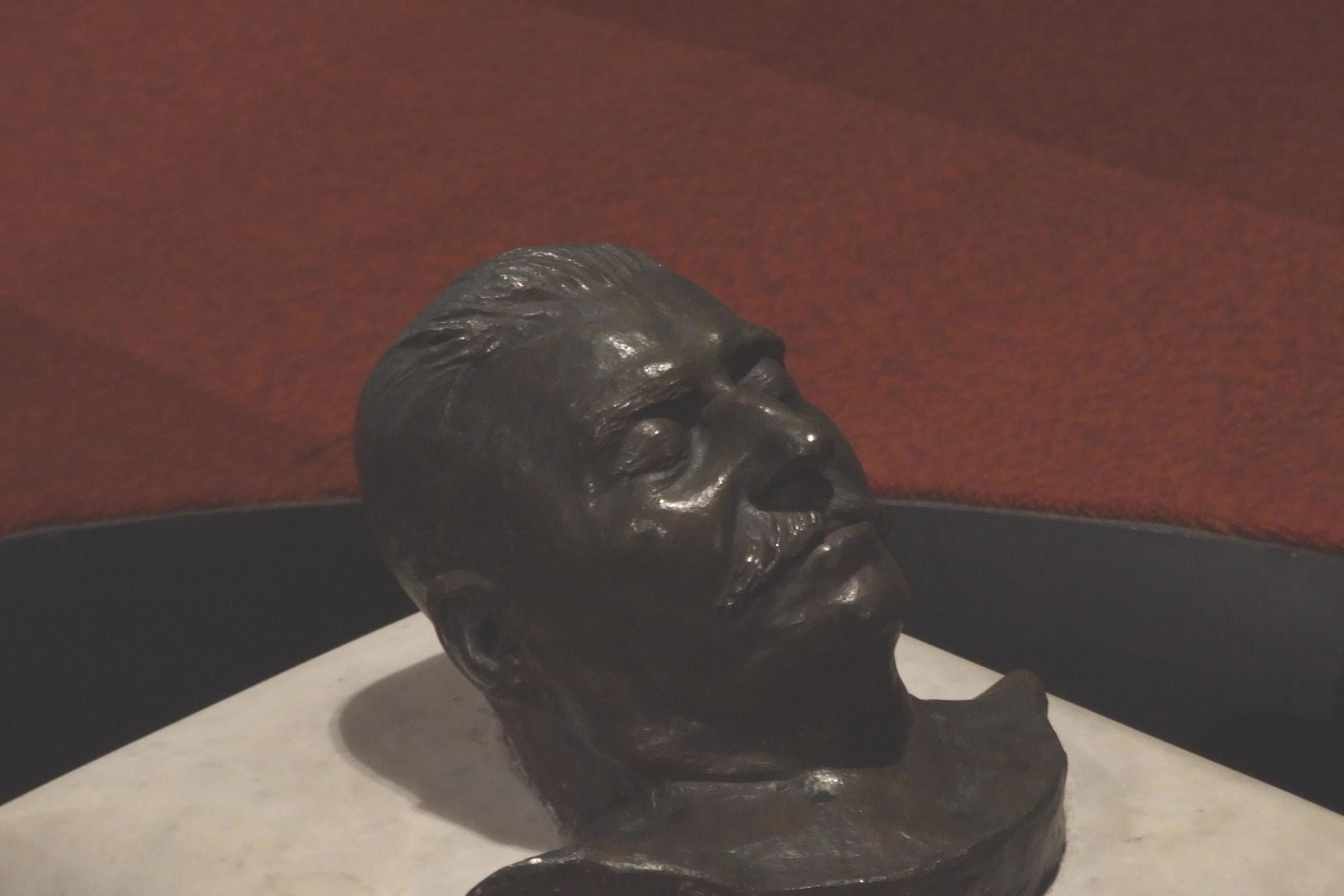

“In no room was the sense that the museum was a shrine more evident than in the room with his death mask,” William Joseph Altman, an American Peace Corps volunteer stationed in Georgia, tells me. “It was similar to walking into a house of worship.”

The death mask room – a small amphitheatre submerged in darkness at the centre of which a bronze mask of the dictator, moulded shortly after his death, rests atop an altar-like stand bathed in light – is probably what earns the museum a five out of 10 on a “dark tourism meter”; “Maybe not a place to take the kids along to,” is the verdict.

Notably absent on the museum’s main floor is any sign of Stalin’s murderous practices and policies. It was only in 2010 that a small room meant to simulate a gulag cell was added in the basement. There, our guide concedes that there were some deaths. “But these were difficult times,” she adds.

The consensus among historians is that Stalin’s purges, forced displacements, famine-causing policies and murders resulted in some 20 million deaths over his 30-year rule. And that’s a conservative estimate: literary giant Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn, whose novel The Gulag Archipelago draws on the author’s time in a Soviet labour camp, argued the toll came closer to 60 million.

Back at the museum, our guide draws our attention to a signature on a yellowing decree: Iosif Dzhugashvili. “Here Stalin signs his name in Georgian because he always loved Georgia,” she says and cracks what may approximate a smile. A member of our group groans.

Stalin is generally reviled in Georgia due to the series of repressions the small Caucasus nation suffered when, under Stalin’s command, the Soviet Union invaded in 1921 (Georgia was briefly independent after the Russian Empire collapsed in 1918). And to this day, anti-Russian feelings run deep, especially following the five-day Russo-Georgian War of 2008. While Russia continues to lay siege to Georgia’s geopolitical soul, Georgians are eager to be taken up by that other continental superpower, the European Union.

And yet, despite its Soviet and Russia-imposed bloody history, some Georgians are proud to lay claim to Stalin – a powerful leader for all his faults, they say. That rings especially true in Gori.

“Stalin’s continued popularity in his native country is not so much related to Georgia’s nostalgia for the Soviet Union but rather linked to his Georgian roots, producing an inherent sense of nationalism,” Japaridze says.

Altman has witnessed firsthand the contradictory nature of Georgians’ respect for Stalin and simultaneous hatred for Russia. “I was at a supra [typical Georgian feast] once where one of the men’s toasts were literally, ‘Yeah Stalin! F*** Russia!’,” he says. “It was really weird how one of the fathers of the USSR was still worshipped as a hometown boy done good.”

Tour over, our group files out into the sunshine, where a ring of selfie sticks envelops Stalin’s home.

Travel essentials

Getting there

Gori is a one-and-a-half hour drive from Tbilisi International airport. Georgian Airways (georgian-airways.com) flies direct from London Gatwick from £336 return.

Staying there

The Anna Guesthouse (booking.com/hotel/ge/gori-60-gori.en-gb.html) in Gori offers a shared kitchen and lounge, and rooms come with a balcony with a garden view. It’s conveniently located a 10-minute walk from the Stalin Museum. Doubles from £14, room only.

More information

Access to the whole Stalin Museum (stalinmuseum.ge) complex accompanied by a guide costs 15 lari (£4.15); children under six go free.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments