The Independent's journalism is supported by our readers. When you purchase through links on our site, we may earn commission.

Getting spiritual in Serbia

Valerie Singleton discovers hidden treasures in the monasteries of the Raska region

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.The wooden gong summoning us to prayers resounded around the passageways. I leapt out of bed in my small room to shower and dress, quite forgetting I'd been told the first gong was at 4.30am and there would be two more before I needed to be up for the liturgy at 6am.

The Gradac Monastery, where I was staying the night, was in the mountainous Raska region of south-west Serbia, very near the border with Kosovo. I was honoured; I'd been given the room the bishop uses when he visits, which meant I had a loo and a shower.

It was too cold to use the Church of the Annunciation, so the liturgy was held in the refectory, which had been transformed into a small chapel. The service lasted two hours and was strangely calming. It was conducted by Father Vitalije, the only priest who lives at Gradac. Then, with the refectory converted back into a dining room again, I had breakfast with Sister Anna before taking a look at the 13th-century church and its frescos.

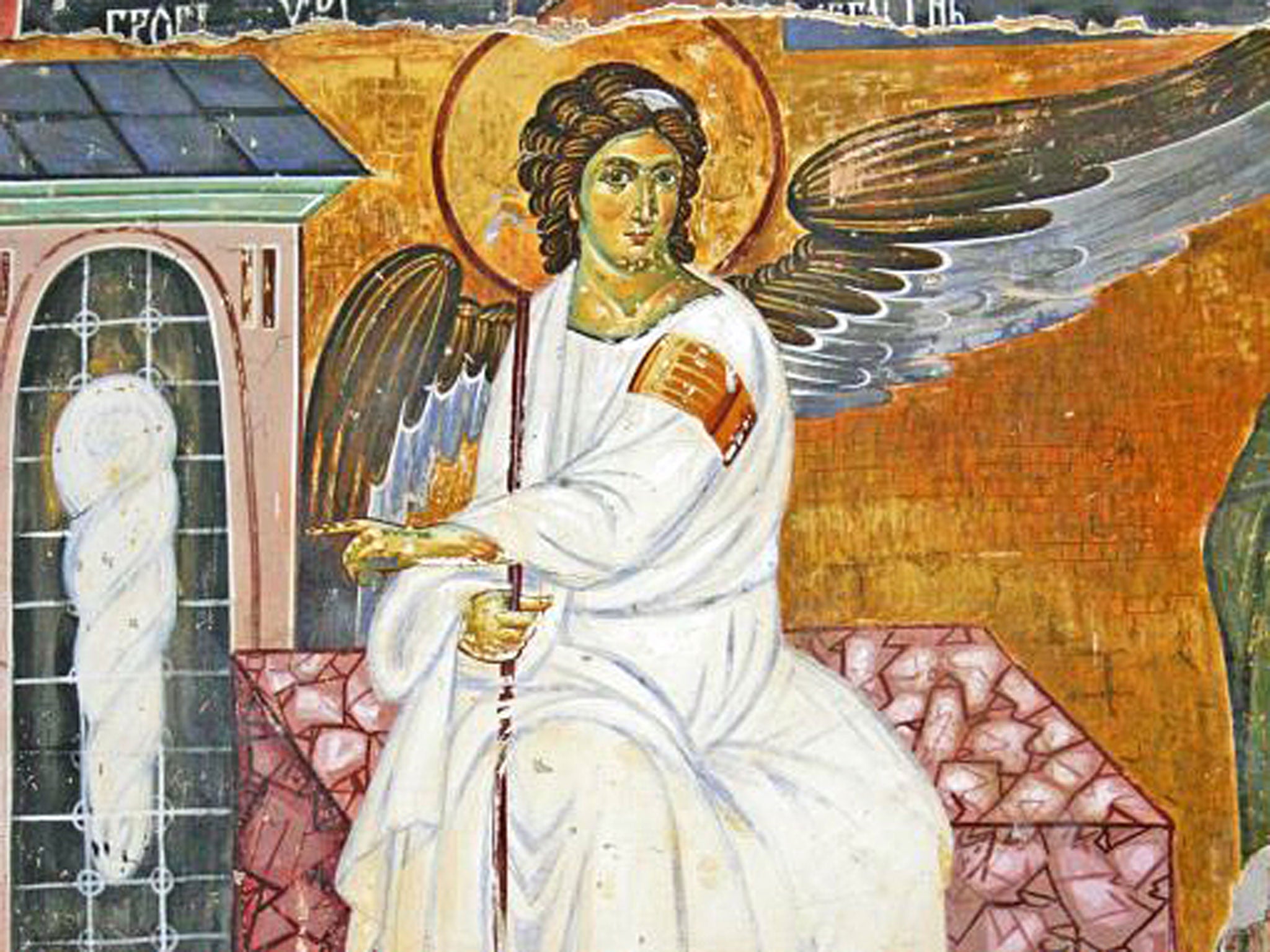

Most of the figures were damaged but the colours were striking, especially the rich blues. There was a fairly intact Annunciation and a delightful Virgin Mary and Child where Mary, sitting in what looked like a bright red bucket chair, tenderly rested her head against the baby Jesus in a rather odd crib.

I had been given three maps when I'd arrived in Belgrade a week earlier. A tourist map, a map of the wine routes and a map of monasteries. Unfolding the latter, I'd been astonished at their sheer number. I counted 74, including those over the border in Kosovo. The building of many of these took place in about the 12th century, when Stefan Nemanja converted to Christianity and created Serbia's first independent medieval state, centred on Raska and named after the River Raska, or Ibar, which flows through this wild landscape. Raska also became a term to describe a style of architecture for the monasteries in this part of the country.

These monasteries are Serbia's hidden treasure. Many contain superb frescos, a great number in surprisingly good condition, despite centuries of neglect and exposure to the elements. Some of the monasteries are on Unesco's World Heritage List, and many have dormitories where visitors are allowed to stay at very little (or no) cost.

With only a few days at my disposal, I'd decided to follow the trail of Serbia's national saint, St Sava (Stefan Nemanja's son), and visit five monasteries associated with his family and that early medieval state. My guide was the charming and knowledgeable Srdjan Ristic. "Let me tell you about St Sava," he said. "Sava is very important for the Serbian people. He was Nemanja's youngest son, who eventually became a monk and founded the Serbian Orthodox Church and became its first archbishop – so now he's our national saint."

Sava was buried in Mileseva Monastery in 1236, although in 1594, as a reprisal for a Serbian uprising, the Ottomans dug up Sava's remains and took them to the Vracar Plateau on the edge of Belgrade. "They burnt them in full view of the inhabitants of the city," said Srdjan. "Today, on exactly the same spot, we're building the Cathedral of St Sava, which is larger than Hagia Sophia in Istanbul."

Mileseva Monastery lies on the edge of the River Milesevka, around 250km from Belgrade. There isn't much around aside from the monastery, a few village houses spread over the low hills and one café where the lights had fused. Srdjan took me inside the church, to see the White Angel, one of the country's most valued frescos. Painted as long ago as 1235, it is still in excellent condition and depicts the Angel Gabriel waiting at Christ's empty tomb.

The next day, we reached our second monastery: Sopocani. Sopocani was built by King Uros I, another grandson of Nemanja. The church was left in ruins and had no roof for more than 200 years, so it is remarkable that, even in the fading light, I could see the walls were covered in frescos. The artists are unknown but it is thought they were painted in the late 13th century. The Ascension of the Holy Mother of God, with the Virgin Mary lying on a vast bed draped in sumptuous fabrics, was proclaimed the most beautiful fresco from the Middle Ages at the 1961 World Exhibition in Paris.

After our night in Gradac, we headed back to Belgrade. "I have two more very special monasteries I want to show you on the way," said Srdjan. "Studenica is one of Nemanjas's most significant endowments. He built it about 1190 and it is now a Unesco World Heritage Site. Our last stop will be Zica. Zica is very different. It is painted red and it is where Stefan was crowned."

Studenica, set in a valley surrounded by mountains, was a bigger and more ornate site than the others I had seen. It had an almost completely circular outer defensive wall, ruins of the original monk's dwellings and a huge new dormitory for guests. There were three churches in the grounds but Nemanja's Romanesque Church of the Virgin, partly covered in marble, was the largest and most breathtaking, with a most moving Crucifixion in deep reds and blues, Nemanja's sarcophagus and a coffin – completely encased in old silver and Russian jewels – which contained the remains of his wife St Anastasia.

Zica proved to be another magnificent Romanesque monastery, an important spiritual centre where Sava became the first Serbian archbishop and where Stefan and many Serbian kings after him were crowned. Perched on a hill near the city of Kraljevo, it was looted many times over the centuries but was now superbly renovated.

I returned to Belgrade happy to have seen five such contrasting examples of Serbian monasteries, but all too aware that, according to my calculations, I still had 69 to visit sometime in the future.

Travel essentials

Getting there

Flights from the UK to Belgrade are offered by Air Serbia (020 8 976 6000; airserbia.com) from Heathrow, and by Wizz Air (0906 959 0002; wizzair.com) from Luton.

Seeing there

Explore Belgrade (00 381 64 153 15 24; explore-belgrade.com) offers day-long tours of monasteries in Serbia from €25pp.

More information

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments