The Independent's journalism is supported by our readers. When you purchase through links on our site, we may earn commission.

Georgia: 'Uncle Joe' lives on in his home town

Stalin is seen through the eyes of his supporters in a museum of his life, says Mark McCrum

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.In the central square of the scrappy little Georgian town of Gori, an hour-and-a-half west of the capital Tbilisi, stands one of the strangest tourist attractions I have ever visited – the Stalin Museum, devoted to the Soviet dictator who died 60 years ago this Tuesday.

From the outside, this colonnaded Italianate palazzo looks like an art gallery or seminary. But step into the marble-floored front hall, see ahead of you the grand flight of red-carpeted stairs, the blue stained-glass windows, the white marble statue on the landing, and you sense something very different.

Even as you queue for tickets, there's an odd, reverential hush about the place – almost as if the great leader himself might at any moment appear. Viewing the exhibition by yourself is not permitted, the stern-faced woman in the booth informed me: I must wait for the English guide.

Some minutes after the Russian guide had taken her party on up the red carpet, I and three other English-speakers were joined by a sweet, toothy young woman in a neat black suit. Upstairs, in the first of three large parquet-floored rooms, I was glad of her commentary (even if it was a little brisk); for though the exhibition is laid out chronologically, the captions are in Georgian and Russian.

It was clear from the start that this was not to be a critical account. Here was Stalin as only his supporters would have seen him: the local boy whose washerwoman mother fervently wanted him to be a priest; the star pupil of the church school who won a scholarship to the theological seminary in Tbilisi; the teenage poet whose work was good enough to be published in the magazine Iveria. Like Hitler the watercolourist, Josef Vissarionovich Dzhugashvili once had his sensitive side.

And as he moved into revolutionary politics in his early twenties, what a dashing-looking fellow he was: thick, flowing hair, dark, thoughtful eyes, beneath the fashionable beard, a mouth both firm and amused.

Neatly organised walls of photographs, framed documents, letters and maps take you on through his early life: seven jail terms under the tsarist regime (six in Siberia); editorship of Pravda; revolution of 1917; civil war; Lenin's death in 1924. The only negative note on display is the text of Lenin's 1922 warning to the Communist Party, describing Stalin as "a coarse, brutish bully" and advising members to remove him as general secretary.

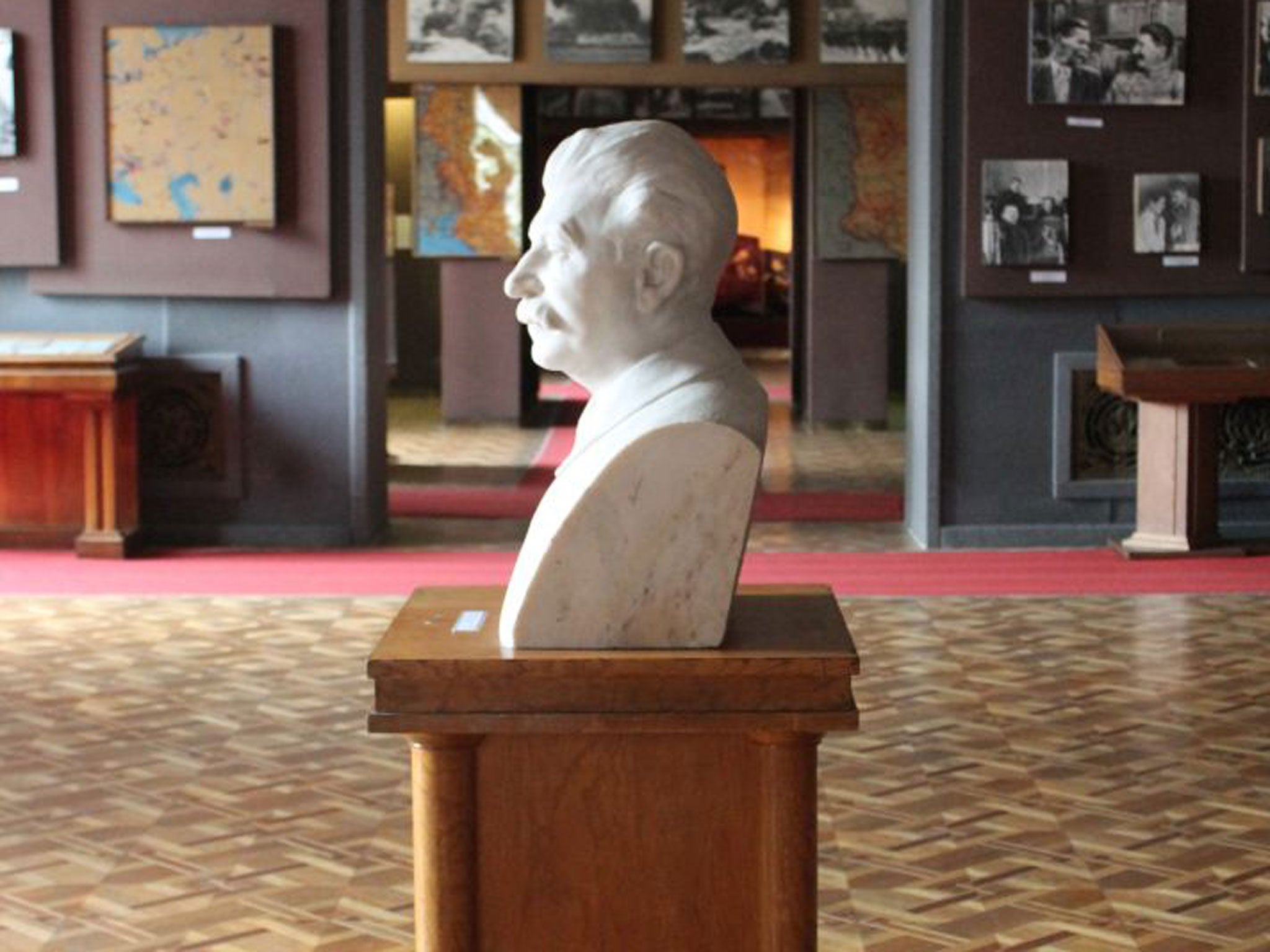

In the second room, the account of events leading up to the Second World War remains almost comically selective: there's no mention of the 1936 show trials of Grigory Zinoviev and Lev Kamenev, or the Molotov-Ribbentrop pact with Hitler in 1939; only one photo shows Leon Trotsky. Away from the walls, the memorabilia is innocuous: a tasselled desk lamp given by a tank factory, an accordion donated by the workers of Gori, busts of our hero on plinths – now looking more recognisable, with bushy moustache and thick hair.

After a third room of photos and maps of what the Russians called the Great Patriotic War, and an adjoining Victory Room, with a fine semicircular photo montage, you turn right into a very spooky chamber. On a cushion-like plinth at the centre of a circle of red carpet, surrounded by thin, square white pillars, lies a shiny black death mask of the dictator, lit by a single shaft of light from the ceiling. Beyond that, another darkened room was full of cabinets displaying gifts from leaders around the world.

But now, as if to counter any accusation that this building was the weirdest time-warp display of Soviet propaganda, our guide led us downstairs to the "Room of Repression", featuring a bare desk and an ancient phone, and beyond a little barred cell, complete with narrow bunk. Though there had been no mention upstairs of the gulag, forced collectivisations, show trials, fabricated confessions, deportations or labour camps, here, it seemed, was a realistic mock-up of the kind of place a dissident might end up. But our sweet-faced guide was saying nothing more. She almost looked embarrassed that the upbeat tone of the rest of the place was a trifle marred.

This recent, below-stairs addition was opened after the 2008 South Ossetia war, when Russia bombed Gori, in scenes also documented here. At that time the Georgian Ministry of Culture announced that the Stalin Museum would be turned into a Museum of Russian Aggression. It would be reorganised, said one MP, to tell "the whole story of Stalin's horrors, in the same way the Holocaust Museum does". For a while, a banner was hung at the entrance which read: "This museum is a falsification of history. It is a typical example of Soviet propaganda and it attempts to legitimise the bloodiest regime in history."

But recent history notwithstanding, local support for their famous son remains, it seems, strong in Gori. On 20 December 2012, the municipal assembly voted to put an end to all plans to change the museum's content. And a 17m statue of Stalin, removed by central government at dead of night in June 2010, is to be reinstated in the central square.

Outside, beyond twin rows of sunlit stone columns, the glorification continued. Under its very own glass-roofed Doric temple stands the tiny wood and mud-bricked house where Josef was born and spent his first four years with his alcoholic cobbler father and washerwoman mother. In this single room, they slept on this 5ft double bed and ate on this sturdy cloth-covered table. Their landlord lived right next door.

As if to track our hero's extraordinary progress, just around the corner is the final exhibit, the armour-plated private railway carriage which Stalin used to travel to the Yalta conference in 1945. (I was amused to see that he favoured a wooden loo seat.)

To round off your visit, you can stop at the shop and buy Stalin T-shirts, cigarette lighters, bottle openers, mugs and even a bottle of the dictator's favourite local wine (semi-sweet Kindzmarauli) with his face on the label. Just perfect for a suitably Georgian toast to the remarkable power of local pride.

Travel essentials

Getting there

British Airways (0844 493 0787; ba.com) flies non-stop from Heathrow to Tbilisi, but only until the end of March. After that you can connect in Istanbul, Vienna or Rome.

Visiting there

The Stalin Museum is at 32 Stalinis gamziri, Gori, served by train from Tbilisi. Admission with guide is 10 lari (£4) or 15 lari (£6) including Stalin's railway carriage.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments