France's battlefields: Forgotten heroes all along the Western Front

Cahal Milmo encounters tributes to the war's far-flung heroes

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Opposite a typical northern French café dispensing beer and frites on the edge of the village of Richebourg, two stone tigers stand guard over a column inscribed with Sanskrit words and a curving screen redolent of a maharajah's palace.

The circular monument, surrounded by swaying willow trees and punctuated by chhatris (dome-topped pavilions) of the sort seen across India, is an arresting sight amid the red brick houses and farmsteads of the Pas de Calais. It is only after swinging open the heavy iron gate and entering the inner sanctum that its doleful purpose is revealed. On its walls are carved 4,742 names of Indian, Pakistani, Bangladeshi and Nepalese soldiers who came to this corner of France in 1914 and died in 12 months of brutal combat on the Western Front. Their remains were never found.

Over the next three years, millions of Britons will mark the centenary of the First World War by crossing the Channel to tour the battlefields where some 890,000 soldiers from these islands fell, amid 13.5m casualties on all sides throughout the conflict. In the Southern Hemisphere, today's Anzac commemorations take on added significance, marking 100 years since the Gallipoli campaign.

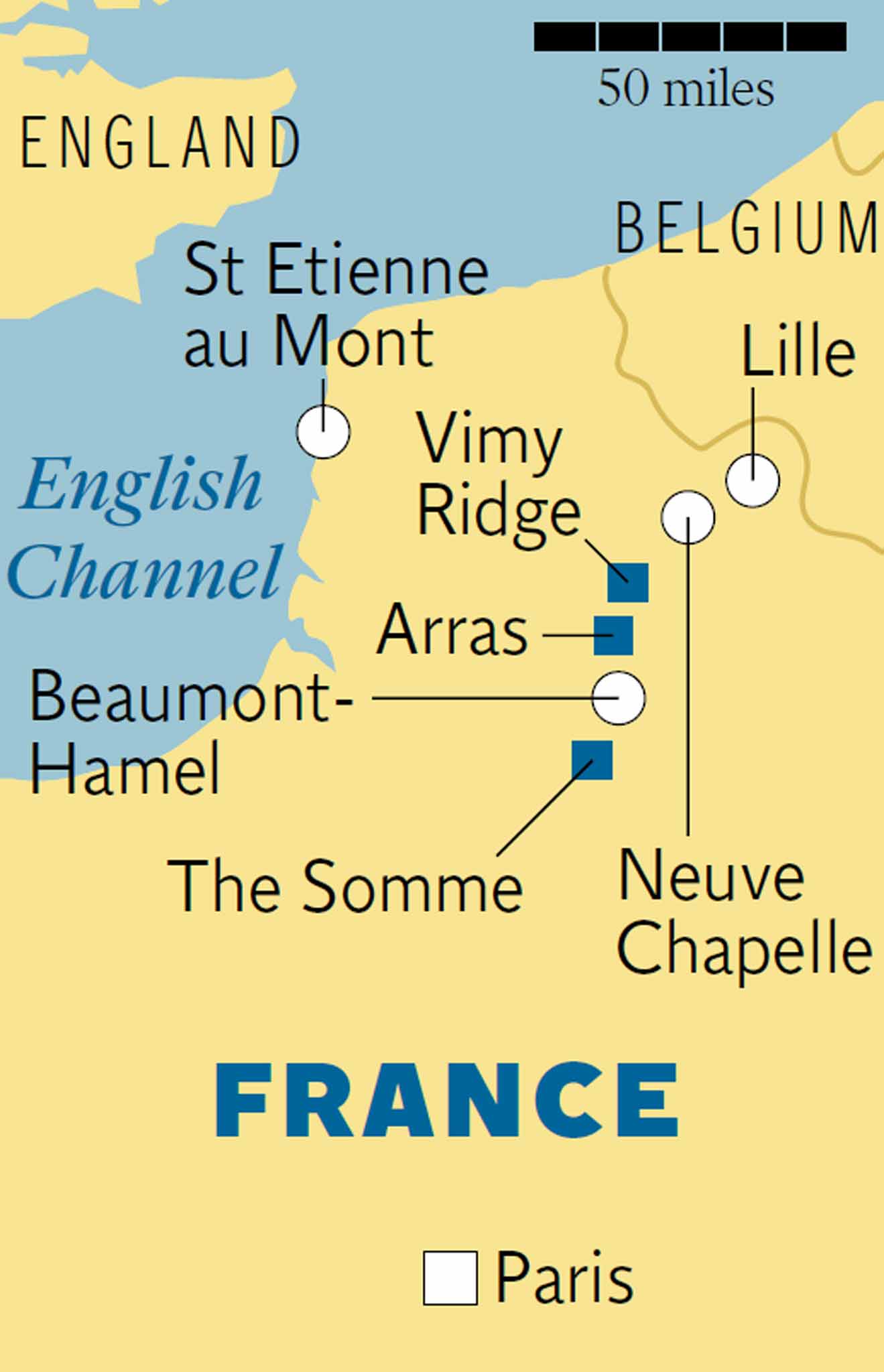

On a 100km stretch of the trenches – from the so-called "Forgotten Front" of Artois, to the west of Lille, to the industrial slaughter of the Somme – some of the most totemic names of the conflict fell: Wilfred Owen and John Kipling, whose father, Rudyard, never forgave himself for encouraging his 18-year-old son to sign up.

But these same corners of France also pay testimony to others who died much further from home and reveal a little told story about how Britain's imperial possessions and some unexpected allies helped secure victory at such a high price. One example of the courage of these men is among the names carved into the walls of the Indian memorial, which sits majestically but idiosyncratically on the corner of a busy roundabout.

On 10 March 1915, Lieutenant Gabar Singh Negi, a Sikh from Uttarakhand in northern India, charged across no man's land with his bayonet fixed and armfuls of grenades in his pockets. He was one of the first Allied soldiers to reach enemy lines in the Battle of Neuve Chapelle, slaying the enemy at bayonet point before himself succumbing to the rain of bullets. He was awarded the Victoria Cross – one of a dozen of his countrymen to receive Britain's highest military honour during the war. But while his family received a medal they, like so many others, received no remains.

Barely 100 metres from the Indian memorial at Richebourg, a surprisng flag flutters above 500 dark grey granite graves. In April 1917, the first troops from the Portuguese Expeditionary Corps arrived at Neuve Chapelle, the same place where, two years earlier, 120,000 soldiers of the Raj distinguished themselves in battle.

By the time of the Armistice in November 1918, nearly 56,000 Portuguese soldiers, invited by Britain to join the war to protect its African colonies, had entered the trenches. Some 7,000 never returned. Part of their legacy is a story that shows how soldiers clung to whatever vestiges of civilisation they could. During the Neuve Chapelle fighting a group of Portuguese rescued a statue of Christ on the Cross from the ruins of the village church between the lines. It was placed in their trenches in the hope it would provide divine protection, and returned to Lisbon as a gift in 1958.

With its gently rolling countryside, punctuated by the meandering flow of the river Somme, the physical evidence of the war is barely perceptible – a carefully-preserved landmine crater here, a fought-over farmhouse there. But the reward of a journey through this part of France is coming across stories of extraordinary human endeavour.

A 30-minute drive from Neuve-Chappelle to Arras reveals the Carrière Wellington, an old limestone quarry. Visitors don headgear in the shape of the soup plate helmets once worn by Tommies to descend into the caverns and inspect the vestiges of one of the more successful surprise attacks of the war, sprung thanks to the industry of a contingent of New Zealand tunnellers.

For eight days in 1917 some 24,000 British and Commonwealth soldiers hid in the galleries of the mine dug by the Kiwis. Girlfriends, imagined or real, and cartoons remain drawn on the walls where the men waited before the attack.

On the coast at St Etienne au Mont stands a Commonwealth War Graves Commission cemetery for the Chinese labourers who worked behind British lines from 1916 on, and after Armistice Day were used to clear mines and bury British dead.

At Beaumont-Hamel, the trenches have been preserved to immortalise where the volunteer regiment of men from Newfoundland – at the time still a separate entity from Canada – was all but wiped out in 30 minutes during the opening of the Battle of the Somme. Of 780 men who advanced, 68 were available for roll call next morning.

There can be few more arrestingly elegant monuments than the soaring twin pinnacles of nearly white stone that mark the Canadian memorial overlooking the Pas de Calais coal basin at Vimy Ridge. Others, such as the new Australian cemetery at Fromelles, are the physical manifestation of the fact that, even a century on, the discovery of human remains from the war is still a regular occurrence.

But perhaps the most affecting commemoration of these far-flung heroes is not yet complete. In the sombre woodland of the Bois Delville, a monument pays testimony to the 10,000 South Africans who died. Until last year, all of the remains were of white South Africans. However in July, the body of Private Myengwa Beleza, who died in November 1916, was interred at the memorial – the first black man, among 600 who died in Europe, to be accorded the honour taken for granted in this land. There are plans for more to follow.

A century on, the true history of the First World War is still being set in stone. As the custodian of the site put it: "Even now, we still have work to do to ensure those who made the ultimate sacrifice are properly commemorated. Everyone deserves never to be forgotten."

Getting there

The writer travelled from London St Pancras to Lille with Eurostar (03432 186 186; eurostar.com).

Staying there

Hotel Novotel Centre Grand Place, Lille (novotel.com/lille).

Hotel Mercure Atria Arras Centre and Amiens Cathedral (mercure.com).

Visiting there

Indian War Memorial, Richebourg (bit.ly/NeuChap); Portuguese National Cemetery, Richebourg (bit.ly/PortCem); Wellington Quarry, Arras (facebook.com/CarriereWellington); Canadian War Memorial, Vimy (bit.ly/CanMem); Australian Memorial Park, Fromelles (musee -bataille-fromelles.fr); Newfoundland Memorial Park, Beaumont-Hamel (bit.ly/NewfoundMem); South African National Memorial, Longueval (delvillewood.com); Historial Museum of the Great War, Peronne (eng.historial.org).

More information

remembrancetrails-northernfrance.com

Commonwealth War Graves Commission: cwgc.org

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments