Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Perched at the top of one of the steep wooden slides that drop between levels in the Berchtesgaden Salt Mine, deep beneath the Austria-German border, I peer down into blackness. Without either a harness, seatbelt or railings, there’s no discernible way of preventing myself from catapulting into the wall at the other end if I reach critical momentum. I cling like a baby spider monkey to the shoulders of the man sitting in front of me, an Australian tourist I met a couple of minutes ago.

We push off from the edge; my stomach bounds; and within seconds we slide to a graceful halt in the middle of the rest of our tour group. A barely audible swish, and our guide, Joseph, lands next to me, with a casual indifference that makes me wonder if he goes down head-first when tourists aren’t around.

The 500-year-old salt mine is cool, dark and dirty – a world away from Salzburg’s Mozart-branded chocolates and double-decker trawling the Sound of Music trail. Some 330,000 people visit the city each year, and tours of the mine have proved popular with those keen to escape the city’s usual haunts – to such an extent that the route is now expanding. One cavern in development when I went earlier this year promised to become an interactive salt gallery, which is now open.

There are a number of salt mines in the area, including Hallein near Salzburg, Hallstatt in Upper Austria, and Altaussee in Ausseerland. Many close for the winter, but Berchtesgaden, which is open year-round, is easy and cheap to get to from Salzburg – despite being just over the border in Germany. The 840 bus, takes you from Salzburg’s main train station to right outside the mine, after a gentle climb into the mountains and an understated Alpine village border crossing. Don’t forget your passport, though; security has been stepped up in recent months and you may be asked to show ID before you enter Germany.

Berchtesgaden wastes no time in getting you into a miner state of mind. Before the tour started we were handed a pair of navy dungarees to wear over our clothes, before we were ushered aboard a miners’ train that rolls – Disneyland roller-coaster style – into the mountain. We disembarked at the mouth of the polished wooden slides that drop down into the “Salt Cathedral” – apparently how Austrian salt miners used to get to work.

Our tour guide speaks little English, but audio guides, triggered at the right locations, fill in the gaps. Having survived the plunge into the Cathedral we pause in the enormous grotto to hear how salt is extracted from the mountains using a process called wet mining.

Roughly explained, once the salt content of the rock has been determined, fresh water is pumped into hollow crevices in the mountain – disconcertingly, as the guide is explaining, a lightshow gives the impression that the cavern is filling up with water. Salt leaches into the water from the rock to create a brine – for the hardy, there is an opportunity to taste some during the tour – and non-soluble material drops to the bottom. The cavern swells as more rock is eroded until a vast, 3,500 to 5,000 cubic metre hollow space remains. These caverns can be used for around 30 years – meanwhile the brine is pumped through a vast pipeline to nearby Bad Reichenhall, where the water is evaporated to leave behind salt.

“It’s three degrees and snowing,” says Kira, partner of my Australian crashmat, when I wonder why they decided to spend the day learning about salt underground. “This seemed like a better option.”

From the Cathedral the tour snakes through well-lit tunnels, between galleries and installations. We stop in the “salt laboratory” to compare our dungarees to those worn by miners hundreds of years ago. But it’s the side-tunnels that remind you how far beneath the ground you are, and how different it would have been without the extensive lighting and signposted toilets. Straying towards the back of the tour group, the silence is absolute.

“Some people do get claustrophobic and scared,” Joseph, the tour guide, tells me. Does he? “No – I come down here alone sometimes,” he explains. “I’m actually an electrician.”

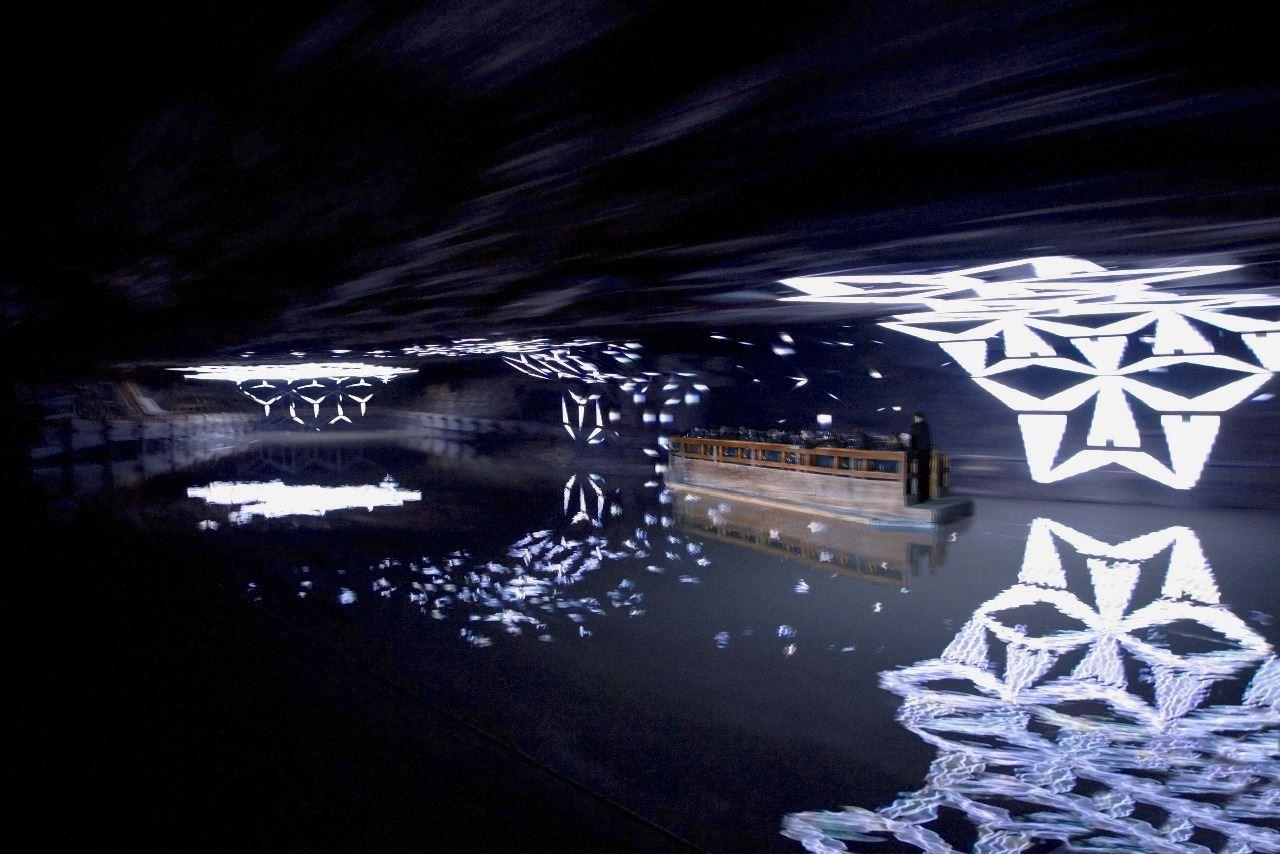

At the deepest point of the tour – 130 metres below sea level – is the Mirror Lake, a mile-long brine lake encircled by total darkness. Its surface is as smooth as glass in the breezeless cavern. We take a barge across, and during the short crossing a light show illuminates the salt crystals in the roof, like an underground son et lumiere. It’s the most impressive part of the tour, and apart from the gentle, ambient music, takes place in awed silence.

We finish at the Reichenbach Pump, one of the 14-tonne bronze pumps that constantly forced the brine out of the mine, 356 metres uphill, for 100 years, until they eventually closed down in the 1920s. Built in the 19th century to transport salt from Berchtesgaden to the processing plant at Bad Reichenhall, the pumps were regarded as engineering marvels of their time. Today, up on the surface, a scenic hiking trail now follows the winding pipeline through the Alps.

An old funicular carries us the 23 metres to the surface – the miners may have had unconventional ways of getting into the caves, but apparently opted for an easier way out – where we board the little mine train and trundle, blinking, out into the bright sun and snow-glare. On a fine day you can sit outside the old machine house – what is now the mine’s restaurant, The Gasthaus Reichenbach, and drink Bavarian lager in the sunshine.

A short 3km walk through the mountains passes by the Enzianbrennerei Grassl, Germany’s oldest gentian distillery, which offers free tours and chances to taste the bitter liqueur extracted from the roots of the alpine plant. But when I visited the roads were piled high with snow and the clouds threatened more, so after a quick plough along the footpath that encircles the mine, I hopped the bus back to Salzburg, to indulge shamelessly in Mozart-branded chocolates and twirl around the Mirabell Gardens.

Travel essentials

Getting there

Ryanair (ryanair.com) flies to Salzburg from Stansted.

Staying there

The Sheraton Grand Salzburg (00 43 662 889990; sheratonsalzburg.com) offers doubles from €140, room only.

Visiting there

Berchtesgaden Salt Mine (00 49 8652 60020; salzbergwerk.de) is open year-round. Tours run every 10-15 minutes, or 25 minutes in winter, take up to 1.5 hours and cost €16.50.

More information

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments