Vietnam's historic North-South railway: Ride the Reunification Express linking Hanoi with Ho Chi Minh City

Built by the French 80 years ago, the history of the line tells the story of a nation, says Mike Unwin as he climbs aboard

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.It's a dilemma: “frog porridge Singapore-style” costs 40,000 Vietnamese dong (about £1.20) but plain “frog porridge” just 28,000. I study my laminated menu as we rattle on south through the night. Does “Singapore-style” mean a spicier sauce, perhaps, or bigger bits of frog?

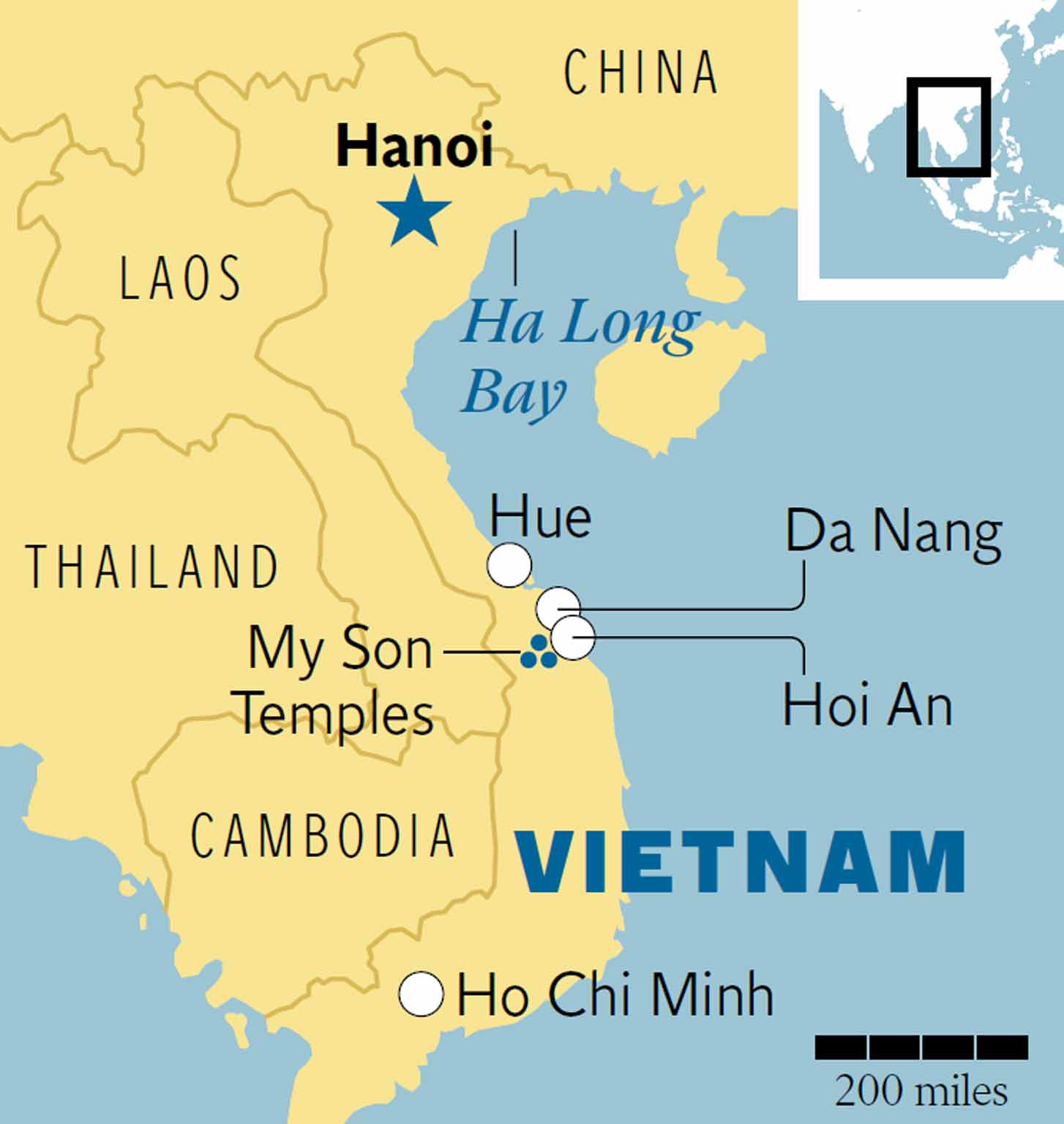

We're travelling on the Reunification Express, the historic train journey that links Hanoi in Vietnam's north with Ho Chi Minh City (still referred to locally as Saigon) in the south. This year marks the 80th anniversary of the railway line's completion by the French in 1936: 80 years that have seen it bombed, abandoned, rebuilt and then, in December 1976, reopened to mark a nation's rebirth, just 20 months after the end of the Vietnam War (although the Vietnamese, who endured three major conflicts during the 20th century, call this the American War). Stay onboard and you can complete the journey in 36 hours; however most tourists allow a week or so, with time to hop on and off en route. This overnight leg to Saigon is the last of our six-night trip.

In truth, my porridge quandary does the Reunification Express a disservice. Had we stayed in our compartment instead of wandering down to what, I now realise, is the staff canteen, we could have had hot chicken and rice from the trolley service.

This train is not, it must be said, the Orient Express. Nonetheless, “soft sleeper” class – a four-berth cabin – is comfortable enough. There is space – just – to cram your luggage under the bottom bunk, plus bottled water and a vase of plastic flowers.

At night we sleep soundly, sharing our compartment with voluble Australian backpackers and more taciturn local commuters. By day, we watch an unbroken panorama of rural Vietnam spooling past the window: buffalo tilling the paddy fields, pagodas sprouting from the forest and rural folk cycling along embankments beneath conical non la bamboo hats.

Turn a map of Vietnam on its side and you'll see a narrow yoke with a rice pannier hanging from each end. The top pannier is the north, with the capital city Hanoi, and the bottom is the south, with the commercial hub of Ho Chi Minh City. “North” and “South” carry a troubled history, with the country once divided at the 17th parallel – halfway down the yoke – and a still palpable division in mindset and climate between the once communist, cooler north and the American-held, steamy south. But in 1976, when the railway reopened, the two halves reunited as the Socialist Republic of Vietnam. Hence Reunification Express.

Our journey started in Hanoi, where guide Mary stressed that this ancient city remains the country's beating cultural heart. And she was determined to cram as much culture into our two days as she could. In the Museum of Ethnology we explored the bamboo longhouses of the Ede forest people. At the Temple of Literature, dedicated to Confucius in 1070, we admired huge stone turtles, their heads worn smooth by generations of scholars who stroke them for good luck. And at the Hoa Lo Prison – dubbed “Hanoi Hilton” by its American prisoners of war – we saw where former US presidential candidate John McCain was once incarcerated.

The next day, we cruised Ha Long Bay – a Unesco World Heritage Site four hours east of Hanoi, and Vietnam's most photographed panorama. Some 2,000 forested limestone islets punch up improbably from the placid water – pearls, according to local legend, crystalised from the breath of a dragon. The best way to appreciate Ha Long Bay is, apparently, to overnight on a houseboat, but we had a southbound train to catch.

A night on the rails deposited us at the city of Hue, where our guide, Ngaia, awaited. Hue sits halfway down Vietnam's 3,260km of coastline. The seat of ancient ruling dynasties, it remains a bastion of royal tradition. Ngaia led us around the Imperial Palace where moated citadel walls screened glittering altars to Buddhism, then to the Thien Mu pagoda. As evening fell, we boarded a dragon boat on the Perfume River, the incense of the pagoda blending with the earthier aromas of riverbank life.

The next leg was on to Da Nang. We watched Korean movies while jungle-clad mountain slopes rushed past the train's window, opening suddenly to vistas of beach and lagoon. On disembarking, we headed south-west – passing the stone-carving villages of Marble Mountain – on the road to My Son – an extraordinary temple complex in a valley that's described as the world's largest natural altar to Hinduism. A history of fire, conflict and neglect saw the temples reclaimed by jungle until the French “discovered” them in the 1880s. Restoration work was undone when the Americans, learning that the ruins hid Viet Cong forces, bombed them to rubble. Today, decades of meticulous work has seen the site slowly restored.

If My Son is a temple to Hinduism, the historic port of Hoi An is a temple to trade. Tailor-made suits, silk tablecloths and inlaid lacquer-work boxes all await your credit card. Not that the place isn't charming: its historic walls, canals and covered bridges have earned it Unesco protection.

The next morning, a violent downpour cut short our walking tour and, as the long threatened typhoon worked up a head of steam, we headed out of Da Nang Station bound for Saigon.

By mid morning the next day I'm on my hands and knees in one of the Cu Chi tunnels: a subterranean labyrinth outside Saigon that once hid Viet Cong, who would have dashed along here at a crouched run. I inch along with all the grace of an elephant seal and, after 30 claustrophobic metres, find relief in the steps out and the grinning face of our guide, Long. We see an array of fiendish pit traps with revolving spikes and poisoned stakes, in which unwitting GIs came to grief. And, in a video, we learn how “the ruthless American bombs descended to mercilessly kill the gentle people of the peaceful countryside”.

Due east of Cu Chi, in Bien Hoa City, a barge recently struck the Ghenh railway bridge over the Dong Nai river, severing the great North-South link. For now, passengers have to disembark and complete the final stage to Saigon by road.

If the Cu Chi tunnels have a tourist frivolity, the War Remnants Museum is more sobering, with galleries dedicated to such horrors as the appalling legacy of Agent Orange. It is a relief, to step out into the city. The elegant boulevards, Notre Dame cathedral and the old post office, now displaying a giant portrait of Ho Chi Minh, remind us of French colonial days. And the statue of the three-year old on horseback who, legend says, defeated the Chinese wielding only a bamboo stick, reinforces how this country has never bowed to invaders.

And yet, for all the scars, Vietnam seems to accommodate every ingredient from the past. Turning a street corner, I spy yet another looming portrait of the venerable leader. Then I look closer. It's Colonel Sanders. Perhaps fried chicken is the new imperialism.

Getting there

Mike Unwin travelled with Railbookers (020 3327 0869; railbookers.com), which offers a six-night holiday from Hanoi to Ho Chi Minh City following the path of the Reunification Express with stops in Hue, Hoi An and Danang, from £1,109pp, excluding flights. It can also tailor a holiday to your exact requirements.

Hanoi and Ho Chi Minh City are served from Heathrow by Vietnam Airlines (020 3263 2062; vietnamairlines.com).

More information

British passport-holders can travel to Vietnam for up to 15 days visa-free until 30 June. For travel thereafter, contact the Vietnamese Embassy in London (020 7937 1912; vietnamembassy.org.uk).

Click here to view Asian tours and holidays, with Independent Holidays.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

0Comments