The Independent's journalism is supported by our readers. When you purchase through links on our site, we may earn commission.

Kyushu: Why tourists should forget Honshu and visit this underrated Japanese island instead

Japan’s third largest island is about to get a lot more popular, playing host to several Rugby World Cup matches in 2019; here’s why you should get in there before the crowds start arriving

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.“Welcome to paradise!” says the naked, middle-aged woman sitting beside me, grinning as she sinks deeper into the almost-too-hot spring water pool at Hotel Shiragiku in the Japanese city of Beppu.

She has travelled from Hong Kong to visit the laid-back spa city famous for its 2,500 mineral-rich hot springs, which are said to soothe the skin and relax the body. I nod my head interestedly to feign comfort and hide the fact I am becoming increasingly anxious that she can see my nipples through the water.

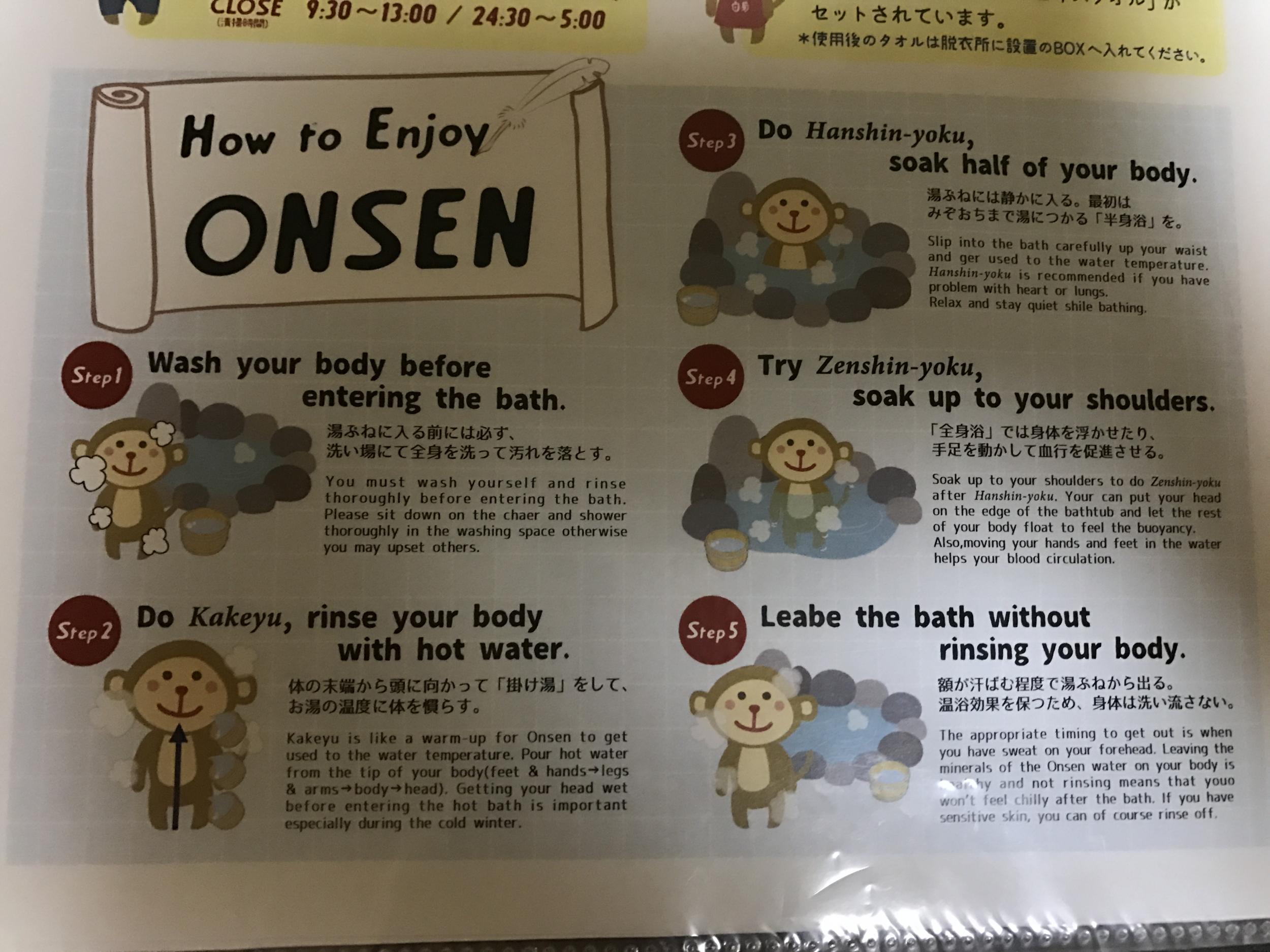

A Londoner uninitiated with onsen culture, I’m seemingly the only one of the dozen naked women in this hot spring bath to feel even a modicum of awkwardness at being in the nude with strangers. Having endured in Japan for thousands of years, onsens are much older than swimsuits and such clothing is thought to contaminate the spring water heated by the Earth’s crust. Instead, bathers must wash thoroughly in a communal area before entering the pool.

I try to relax; it would be remiss to let a little awkwardness get in the way of a dip in an onsen, an integral part of experiencing Kyushu, Japan’s third largest island. And I quickly learn there is something cathartic and freeing about chatting and relaxing communally. This is the antithesis of being shut away in a massage therapy room.

When planning a visit to Japan – especially if it is a once-in-a-lifetime splurge – there’s a risk of Kyushu being eclipsed by the lure of Honshu island. After all, both the sprawling capital of Tokyo and the ancient temples and palaces of Kyoto are located there. However, as several 2019 Rugby World Cup matches are scheduled to take place at Hakatanomori Stadium in Kyushu’s capital of Fukuoka, it’s a destination that is set to become more popular.

At the same time, Kyushu is hardly untouched by tourism. The illustrated English language onsen dos and don’ts guide on display at Hotel Shiragiku, the traditional ryokan inn where I’m staying, is proof that international visitors are by no means a rarity.

A 10-minute taxi ride from the hotel, past plumes of steam which rise from the hot springs, I find relaxation is also a public affair on the shores of Beppu Bay. At the ground-level sand bath overlooking the Seto Inland Sea, a woman uses a shovel to cover my body in wet sand. My head is one of nine poking out rather comically, resting on a wooden block and shielded by a miniature yellow umbrella.

Rather than inducing claustrophobia, the weight of the dark sand presses the tension out of my body like I’m a tube of toothpaste. And this time, after I emerge like a zombie from the sand, peeling my yukata kimono from my body and reclining nude into the onsen feels like second nature. My eyelids heavy, my body hums with a feeling of serenity that I haven’t experienced in years.

As I continue to explore the northern half of Kyushu, I realise a slower pace doesn’t equate to a lack of attractions. Take Fukuoka prefecture’s resplendent 1,113-year-old Dazaifu Tenmangu shrine, where worshippers pray and tourists wander quietly, snapping photos. Modest roadside statuettes, some no more than a few feet tall, reflect how important Shintoism is in Japan.

A few hundred yards from the approach to the shrine is an incongruously modern Starbucks, albeit a beautiful one. Featuring over 2,000 wooden batons that resemble a bird’s nest, the design, created by renowned architects Kengo Kuma and Associates, was much-praised when it was unveiled in 2012. The shops around it sell touristy knick-knacks and freshly fried umegae mochi buns filled with red bean paste.

Then there’s the picturesque Kyushu Olle mountain trail of Oita prefecture. It snakes from Fukkoji temple – the oldest wooden structure on the island and the site of an 8m-high mountainside carving of Buddha believed to date back to the late 1180s – to the Takeda castle town, home to the Hanamizuki onsen. There, I test my mettle with a shocking bath, which sends fast vibrations through the water; it’s believed to soothe joint pain.

A world away from the onsens of Beppu, but still punctuated by Shinto shrines, is the capital of Fukuoka. As the sun sets across its skyscrapers, motorbikes with shed-like yatai mobile street food huts emerge from backstreets like strings of ants, and set up shop along the port city’s Naka river and its neighbouring streets.

As I slurp tonkotsu ramen noodles in one of the pokey yatais that fit a dozen diners at most, I savour the welcome weariness that comes with exploring a new metropolis.

In the bustling Tenjin electronic district I encounter a troupe of Gangura. The members of this subculture have orange, fake-tanned skin, textured hair extensions, thick eye makeup and contoured noses and cheeks, and happily pose for cameras.

Turning a few corners west, I find the fashion-forward vintage stores and graffiti-daubed walls of the Daimyo district in the centre of Chuo ward. After dark, this is where young people gather to eat, drink and dance until late in the city’s night spots.

Drinking in the view of Hakata Bay from the 25th floor of the Hilton Fukuoka Sea Hawk, I notice the satisfying buzz of city life has worn away a little at the sense of tranquillity I built up from my sand bath, which now feels like it happened months ago – and I wonder where the nearest onsen is…

Travel essentials

Getting there

Finnair (finnair.com) flies from the UK to Fukuoka via Helsinki from £695 return.

Staying there

Doubles at Hilton Fukuoka Sea Hawk (hilton.com) from ¥11,662 (£78), room only.

A traditional Japanese room at Hotel Shiragiku (shiragiku.co.jp) costs from £200, B&B.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments