India's rich textile heritage: Exploring the fabric of a nation in Delhi and Jaipur

Fashion designers and artisans take authentic traditions to the next level in two very different cities, writes Rebecca Gonsalves

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.When we think today of clothing “made in India”, it tends to be of mass-produced fast fashion and the sort of factory conditions which are uncomfortable to consider, much less endure. But that has not always been the case. In fact, the country has an artisanal textile tradition that can be traced back to the third century, and which has inspired much of the way fabrics are woven, dyed and decorated today.

It was with this in mind that I travelled to Delhi and Jaipur to gain an insight into this fascinating heritage. On arrival in the capital, it wasn't so much the wave of intense heat that made me feel like I was drowning on dry land, but the cacophony of sound: a constant beeping of car horns used here as an indicator, friendly greeting and simply to puncture any possible moment of peace.

At the city's centre is the civic district known as Lutyens' Delhi, named after Edwin, the architect responsible for so many of the municipal buildings here that line the leafy avenues that are continuously being swept and tended to. The area is verdant and tranquil, a real contrast to the hectic walled city of Old Delhi, and offers much in the way of sightseeing, including the vast National Museum.

Within this stone building I was able to take a close-up look at a mid 18th-century tapestry that provides one of the main focal points for the V&A's Fabric of India exhibition, which opens in London today.

The vast length of fabric depicts the story of Rama and Sita – the central characters of the epic Hindu poem, “The Ramayana” – through the use of indigo dye and embroidery. The colours are still remarkably vibrant, although some old crude repairs highlight the importance of the museum's conservation work.

The permanent galleries display traditional costume, highlighting the diversity of dress across this vast landmass throughout history: from the ornate embroidered creations of the court of the Raj to ceremonial costumes of tribes from the north-east regions including the Naga (Nagaland), Mizo (Mizoram) and Mishmi (Arunachal Pradesh). With few other visitors, there was a stuffy stillness to the museum that made it feel somewhat forgotten.

In comparison, the National Handicrafts and Handlooms Museum was a breath of fresh air – literally so thanks to its extensive use of outdoor spaces, with welcome shade provided by plenty of trees.

Here artisans are given pitches for one month to sell their handmade goods that range from cheap trinkets and souvenirs to much more grand and elaborate fabric prints and woven textiles. But it is in the gift shop that many of the authentic traditional fabric and craft skills are brought to life. Here are beautiful scarves painted, dyed and embroidered in traditionally inspired feminine patterns as well as chic fabric homewares. Lunch is well worth the stay, sitting at a table outside Cafe Lota, where the food is fresh and fragrant – it is easy to see why this has become something of a hotspot among local creatives.

A short walk to the south-west is Khan Market, an area that reveals plentiful delights, not least Good Earth, a shop that combines traditional textile techniques, such as block printing and hand embroidery, with an up-to-date luxury design aesthetic. Homewares are the main focus, but the cafe is no less enticing – with seating on a veranda it's a wonderful place to enjoy a restorative cup of chai.

However, this down at heel rabbit's warren of shops is deceiving – Khan Market flaunts the city's most expensive real estate, so don't expect to pay rock-bottom prices. Other shops in this higgledy-piggledy strip include Anand stationers – a bounty of hand printed cards and wrapping paper. Slightly hidden away, Anokhi is worth the hunt for its lightweight cotton robes in beautiful colours and patterns that cost around 1,550 rupees (£15).

Delhiites are a nocturnal bunch – fitting in a disco nap after finishing work before re-emerging late in the evening ready to socialise. As such, Khan Market comes alive in the evening, as does Hauz Khas Village to the south, a ramshackle but affluent neighbourhood in which boutiques are squeezed between restaurants, bars and clubs.

It is in these boutiques that you will find modern clothing labels such as Pero, which deftly combine traditional Indian textile techniques and fabrics with an international aesthetic and would look just as at home in a boutique in Shoreditch or St Germain as they do there. Many shops, such as Loom Mool, emphasise their connections to artisans and co-operatives.

A 10km drive south-east to Noida district transported me to the heart of Delhi's clothing factories and fashion studios. Manish Arora – who shows his embellished, extravagant creations at Paris Fashion Week – has a studio here populated by hard-working young men who embroider by hand, cut and sew his designs.

Another local label is Abraham & Thakore, whose aesthetic focuses on print patterns and khadi textiles – a term for hand-spun and hand-woven fabrics that is an important part of India's recent history.

Khadi, also known as “freedom fabric”, was part of Mahatma Gandhi's movement towards self- reliance for post-colonial Indians, and both the process of production and the finished fabric are still venerated. The smell of petroleum from the fabric dying process was overwhelming at times, but seeing the vendors by the side of the road was fascinating: from fruit sellers to barbers, convenience is king in this industrious community.

Operating on a far smaller scale, Shahpur Jat is a south Delhi neighbourhood where design start-ups, branding agencies and small shops such as Olivia Dar, Lila and Second Floor Studio radiate a hipster vibe.

This is a community of young designers, and many live as well as work in the area, popping in and out of each other's studios or meeting in Les Parisiennes café to share advice and gossip over a cup of chai.

At hole-in-the-wall stores, shelves were stacked high with boxes of beads and trims, the walls and floor streaked with run-off dye – indigo, saffron, red. A bi-annual open-house scheme means that the curious are able to take a look behind usually closed doors each autumn and spring.

While Delhi leads the charge for modern Indian fashion, Jaipur follows at a more languid pace. It took me under an hour to fly to the capital of Rajasthan from Delhi, but the difference was remarkable.

In the Old City, a master craftsman worked in a studio surrounded by haphazard stacks of audaciously coloured fabrics. He worked quickly, first mixing the frothy dyes in separate pails then methodically knotting fabric using a wooden tool, his ink-stained fingers moving nimbly, before dipping it into each dye in order. Known as resistance dyeing, the knot stops the dye penetrating the threads in certain areas while the order dictates which colours will stay and which will be overridden.

Even in the master's hands the technique looked complex, and the intricate patterns it produced attested to the skill involved.

Jaipur – known as the pink city for its rose-tinted walls – is both romantic and majestic, not least at the City Palace Museum, housed in a complex of repurposed palaces. Among them is a textile and costume gallery, with artefacts, clothing and textiles dating from the 18th to the 20th century. Every room was crowded with people looking at the exhibits of patchwork, embroidery and weaving that lined the walls; the dense gold embroidery of a Divali dress was particularly striking.

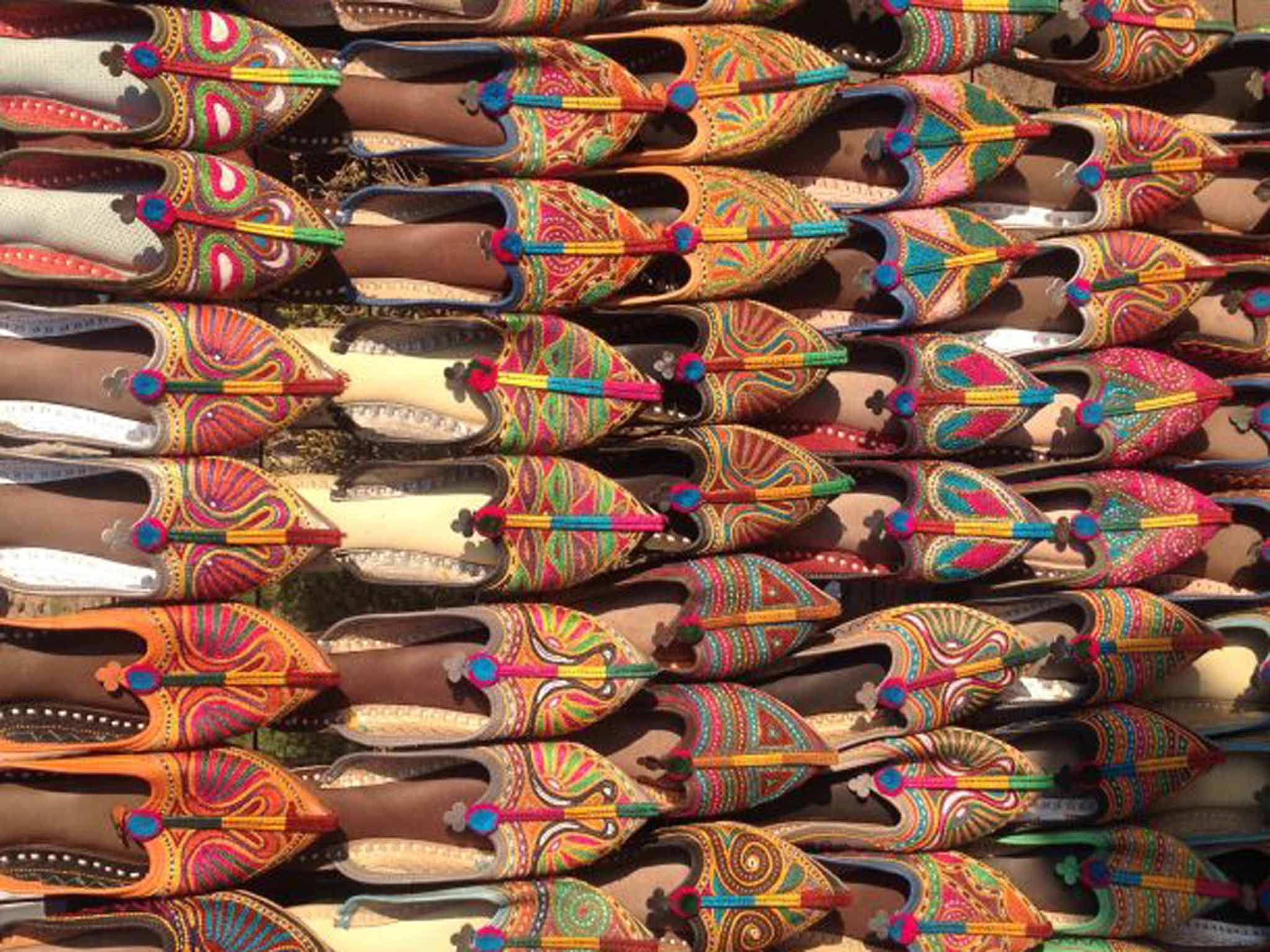

The tradition of ornate special occasion dressing remains an important part of Indian culture, and on my visit the sprawling marketplace in Jaipur was filled with bartering bridal parties looking for something special among the wares of the sari salesman. Embroidery studios were occupied almost solely by men, crowded around fabric stretched over frames, working together to build and create intricate patterns of beads, sequins and stitching.

On the 12km drive out to the town of Amber, the honking traffic was enhanced by elephants painted in bright pastel patterns, ferrying both people and goods. In Amber, Brigitte Singh's vast studio complex was a startling oasis amid the arid landscape of rural Jaipur.

The French-born artist moved to the area in the Eighties as part of her studies, but fell in love with the textile tradition – as well as the son of her mentor – and has lived and worked here ever since.

Her Mughal-inspired prints are highly regarded, and watching the printers at work, precisely mapping out and building the vast prints block by block was a mesmerising process.

After being fixed, washed and ironed, the fabrics are sewn into everything from quilts to glasses cases and children's clothes which would give Liberty a run for its money, and all proudly bearing that “made in India” tag.

'The Fabric of India' opens at the V&A in London today and runs until 10 January 2016 (vam.ac.uk; tickets £14).

Getting there

Delhi is served from Heathrow by British Airways, Virgin Atlantic, Jet Airways and Air India.

Jaipur is connected to Delhi by a number of daily flights on airlines such as Air India, Jet Airways, SpiceJet and IndiGo.

Staying there

The Taj Palace in Delhi and Rambagh Palace in Jaipur (tajhotels.com) have double rooms from R7,406/£73 and R19,000/£187 respectively.

More information

British passport-holders require a visa, obtainable in advance from indianvisaonline.gov.in for $60/£40.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments