That Summer: Plane hopping to Arkansas in 1992

Simon Calder saw some of North America’s less celebrated cities at a pivotal time thanks to a cut-price airpass

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.This piece was originally published as part of The Independent’s That Summer series. Find out more about it here.

The Governor’s Mansion was a handsome villa in the only wealthy corner of Little Rock. From a distance, or perhaps through a fog of cigar smoke, you could have mistaken the residence of Arkansas’ top politician for Georgian; in fact, it dates only from 1950.

As I strode up the drive for a closer look, three men in bulky jackets appeared and asked me to leave; tours of the mansion, they said, had been “cut back” for security reasons.

Twenty-eight summers ago, a populist Democrat politician named Clinton was striving to replace an unloved Republican president named George Bush as the most powerful politician in the world. And when Clinton trounced the incumbent in the election of November 1992, he put his home state on the map.

Just a few months before Clinton won the keys to the White House, I visited Arkansas and found a state content to keep its distance from the rest of the world.

Why Little Rock, Arkansas? Why not. In the pre-9/11 days of aviation, Northwest Airlines offered foreign visitors what amounted to a turbocharged, aeronautical version of Europe’s Interrail.

Northwest sold a one-month unlimited travel airpass for $499 (then £335). For under £11 per day, you could spend July or August flying far and wide across the US and Canada, so long as there was a seat available.

In the low-density days three decades ago, there usually was space: high fares put routine air travel beyond the reach of many North Americans.

For a month, I was on permanent standby, with the small print warning that if a proper fare-paying passenger turned up while the plane was still at the gate, I could be asked to leave the aircraft (politely, not a United Airlines/Dr David Dao-style eviction).

The airpass traveller could cut the cost of accommodation still further by taking overnight flights. Those from the West Coast typically departed close to midnight and touched down at the key Northwest hubs of Minneapolis and Memphis at dawn.

Even on domestic flights it was possible to get jet lag. But in those heady days, airlines provided complimentary meals on board. So rather than pay for breakfast at airport prices, it made much more sense to hop on another plane.

You could easily spot the airpass brigade: we would hurry from one gate to another, asking if seats were available.

Northwest’s niche before it was swallowed up by giant Delta was to fly to lots of secondary cities – the places beyond New York, Miami and San Francisco where real America resides. So one morning I landed in the state capital of Arkansas.

At Little Rock airport, the Hertz representative stared blankly at my driving licence. The expiry date, well into the 21st century, was confusing enough; the jumble of letters and numbers in the postcode threw her completely.

“Is this in France?”, she wondered aloud.

Later, the proprietor of the Town Lodge was so pleased that anyone from Britain might want to visit his city and stay in his motel that, in a spontaneous and commercially reckless gesture, he upgraded the room and gave me a discount.

For many people in a nation that had spent 12 years under Republican presidents, hope was the word that summer. Hope was also the name of the small Arkansas town where William Jefferson Clinton was born in 1946. (His father, also called Bill, died three months before the future president was born, when his car ran into a ditch and overturned. Knocked unconscious by the impact, he drowned in a few inches of water.)

In 1953, Bill Clinton‘s mother took her young son to the nearby spa town, Hot Springs, which is where the Arkansas tourist trail really begins (and, arguably, ends). In the summer of 1992, with the Arkansas governor ahead in the polls in the race for the White House, the Chamber of Commerce was already exploiting the Clinton connection by publishing a guide to his childhood haunts.

On my first visit to Arkansas that summer, the Park Place Baptist Church was “celebrating 90 years of serving Jesus on Park Avenue”; some of those years were shared by Bill Clinton. He also enjoyed the outdoor life around the town, which visitors are encouraged to do.

The Mountain Trail is a five-mile scenic drive that takes you to a tower at the summit of Hot Springs Mountain. From here, you can (just) see the former president’s high school on Oak Street, which is where he learned to play the saxophone. You can also appreciate why the terrain comprising steep hillsides and narrow valleys, wreathed in evergreens and studded with cottages, is vouched to be “Little Switzerland”. The label has been misapplied to corners of the world as various as Shropshire and Kazakhstan, but this district of southwest Arkansas has a better claim than most to the title.

One canyon is occupied by Bathhouse Row, a string of grandiose sanatoria devoted to the reputed healing powers of steamy water.

The Native Americans who originally inhabited this part of the continent regarded the dozens of geysers that bubble from the flank of Hot Springs Mountain as sacred. But early 20th century investors regarded the source as an income stream, and invested in property.

Hot Springs may not be as beautiful as Bath, Baden Baden or Bali, but at the time it was a favoured spa destination for Americans. The ailing and the curious faced a journey to Arkansas that today would be classed as an adventure of epic proportions, but yet they still came to take the waters in Hot Springs.

Up above the bathhouses, Promenade Row allows you to peer into the backyards of these curious places, and to be splashed with simmering water from occasional rogue springs.

The thrill and the custom wore off during the Depression of the 1930s, when disposable income evaporated and the bathhouses emptied of water and people.

The slump preserved many of the original features. The Fordyce Bathhouse, built in 1915, boasted an exotic plumbing system that connected a seething spring via a spaghetti of pipes to the vital organs of a complex central super-heating system, which in turn fed features such as the Hubbard tub (a rheumatism treatment) and the “electromechano” room, full of lethal-looking devices to cure ills and ease pains.

The top end of Bathhouse Row shudders beneath the awesome sandstone bulk of the Medical Arts Building, a neo-Gothic tower decorated in Soviet-style motifs that glorify the working man.

Of all the Hot Springs shrines to sulphur, the Arlington Hotel is the grandest. The current version opened on New Year’s Eve 1924, with decor from Venice via Hollywood. Al Capone’s favourite room was 443, and the gangster took over the entire fourth floor for his well-armed entourage.

Starbucks has moved into the writing room, but the hotel’s bathhouse opens to the public, so you can submerge in splendour.

The craggy Arkansas hills melt into standard-issue southern plains as you near Little Rock, a state capital of modest achievement and ambitions, but with plenty of friendly people.

The first European arrived in 1722, when Bernard de la Harpe, a French officer, was despatched to explore the Arkansas river. Little Rock was just that; a small boulder that the explorer distinguished from a larger outcrop three miles upriver.

With an early example of the kind of environmental insensitivity that characterises the current White House resident [George W Bush] in 1884, the Missouri-Pacific railroad company unceremoniously blew most of the rock up and incorporated the rubble in the foundations of the rail bridge across the river. The city should really be named Little Stump.

Before a bright, young governor announced his presidential candidature, Little Rock had made international news only once.

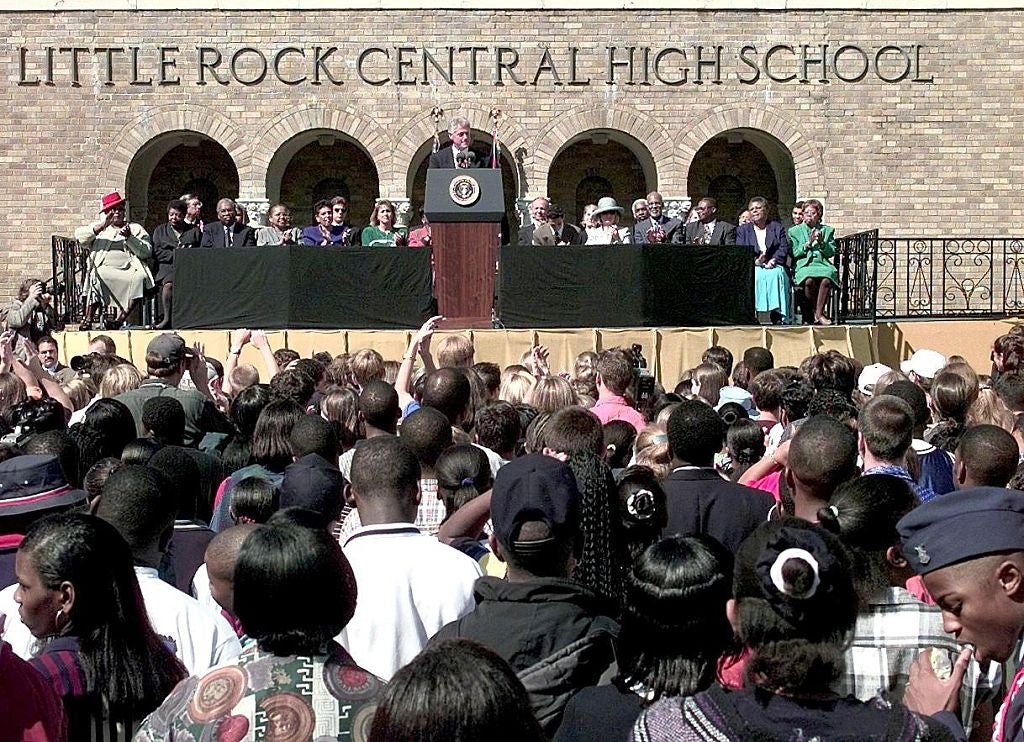

Central High School (which faces onto South Park Street between 14th and 15th Streets) is a daunting yellow-brick castle which looks intended for defensive rather than educative purposes. It is also the only operating high school in America to be designated a National Historic Site.

In 1957, the Supreme Court ruled that schools had to admit black students, and nine African American teenagers in Little Rock became the focus of the nation.

Despite intense provocation from local racist politicians and violence from white families, the children and the civil-rights movement held their nerve. Little Rock drifted back to anonymity.

Bill Clinton’s bid for the most powerful job in the world was run from the old Arkansas Gazette building on the corner of Louisiana and West Third Street. Opposite stood Bennett’s Military Supplies, where the survivalist fearing a Democrat victory could stock up on smoke rockets and army-surplus helmets. It closed in 2018.

That summer, Little Rock was locked into its small-town ways; Lin’s Diner on East Capitol Avenue was a faithful example of the American vernacular culinary art, down to the chrome counter and the slow, syrupy drawl of the proprietor. The standard breakfast platter comprised biscuit, a scone-like lump of dough; gravy, a thick and pallid soup tasting vaguely of dripping; and grits: small-bore tapioca devoid of flavour.

In that summer of 1992, there was one more potential presidential city to visit: Texarkana, home town to a billionaire named Ross Perot. He did not enjoy great respect (Ronald Reagan’s speechwriter described him as “a hand grenade with a bad haircut”), but might have found greater success if he had chosen a campaign manager with a better name than Orson G Swindle.

Texarkana, whose name suggests its location – straddling the Texas-Arkansas border – might have found greater success if it had a better accommodation offering than a boarded-up guesthouse still sporting the sign “Hotel Grim”.

To capitalise on the 15 minutes of fame that Ross Perot’s failed candidature provided, the local Hospitality Association announced a campaign “to enhance Texarkana’s image as a ‘must-see’ city”. I found it more of a “must-flee” city – but on the morning I intended to fly out, I found it difficult to leave. Not a taxi was to be found anywhere. So I walked out to the highway and started hitching to the airport.

With time rapidly running out, I was rescued by a carpet salesman, who told me he wanted neither Clinton nor Perot and was a George Bush supporter. He dropped me at the airport seven minutes before the flight left. In those innocent days, that was enough time to get on board.

I showed up in some other odd places that summer. Until 10 minutes before the Northwest plane left, I had no idea I wanted to go to Edmonton. The Alberta provincial capital is not overflowing with appeal, but from the point of view of a budget traveller, the relative weakness of the Canadian dollar meant a night’s stay would be cheaper than on the US side of the border. And besides, the Airbus A320 had some empty seats.

The airpass era ended less than two years later, in April 1994. But Bill Clinton lives on. And so do Little Rock, Hot Springs and Hope.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments