Day of the Dead: The most underrated celebrations across Latin America

This celebration of life isn’t exclusive to Mexico, says Lauren Cocking. And don’t call it ‘Mexican Halloween’...

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Fluttering papel picado (bunting), bright orange cempasuchiles – also known as Mexican marigolds – and sugary hunks of pan de muerto (”dead bread”) adorn altars across Mexico and beyond on the nights of 1 and 2 November, as families gather not to mourn their dead, but to remember them in life.

But while images of sugar skulls, Catrinas and calacas (skeletons) crowd the popular consciousness when it comes to Día de Muertos – in no small part thanks to Pixar’s Coco – this celebration of life isn’t exclusive to Mexico (nor is it “Mexican Halloween”). In fact, Day of the Dead is rooted in indigenous cultures the length and breadth of Latin America.

Here are eight Day of the Dead (and similar) celebrations you should know about.

Xantolo in La Huasteca Potosina, Mexico

In La Huasteca Potosina, a region to the east of San Luis Potosí state, indigenous Xantolo celebrations reign supreme during late October and early November. Alongside typical Day of the Dead observances, such as the construction of altars, locals pour into squares and parade down streets dressed in intricate attire and carved wooden masks. A carnival atmosphere abides and regional dances are a given, although each town has its own unique set of Xantolo rituals.

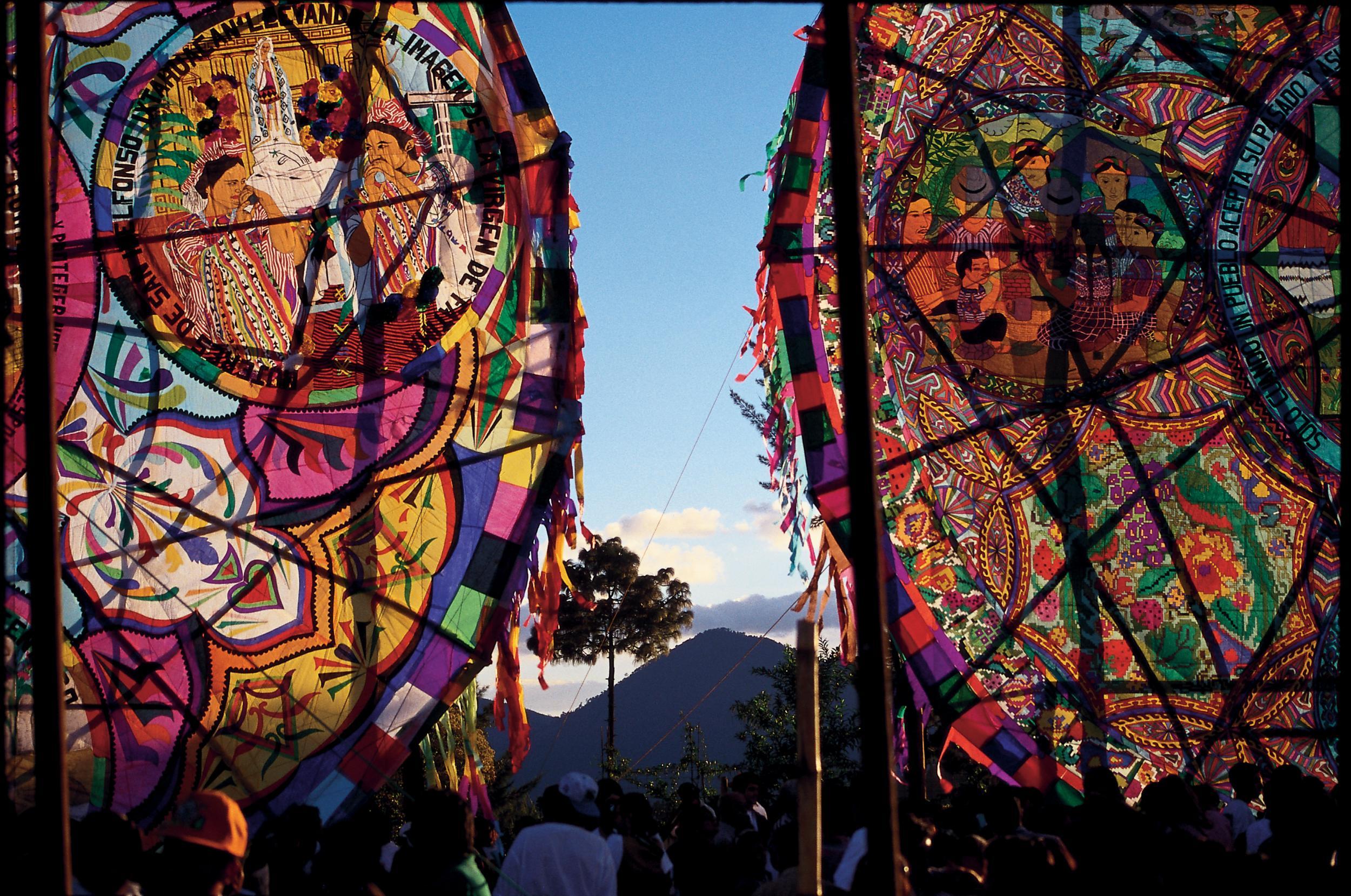

Festival de Barriletes Gigantes in Santiago Sacatepéquez, Guatemala

During the appropriately named Giant Kite Festival on 1 November, Mayan tradition and the Catholic feast of All Saints combine as brightly coloured and bamboo-framed kites dip and dive through the air with surprising grace above Santiago Sacatepéquez and nearby Sumpango. Each kite – which can be more than 30ft wide and decorated with folkloric, religious, or political designs – serves as a way of communicating with the dead.

Día de las Ñatitas in La Paz, Bolivia

Not strictly a Day of the Dead celebration, Bolivia’s Día de las Ñatitas (Day of the Skulls) falls a week later. Many Bolivian Aymaras keep the skulls of their deceased loved ones enshrined in the home as a symbol of good luck. However, it’s on 8 November when Catholic influence and Andean tradition converge and these skulls – often decorated with floral crowns, cigarettes, and coca leaves – are transported en masse to the General Cemetery in La Paz as a sign of gratitude for the fortune they’ve brought to the living.

Festival de la Luz y la Vida in Chignahuapan, Mexico

On 1 and 2 November, thousands of candles, lamps and torches light the way for living and the dead alike, casting an orange glow over the inky night sky as crowds make the pilgrimage from the centre of Chignahuapan, Puebla to the Almoloya Lagoon. There, the Festival of Light and Life begins in earnest with a folkloric performance, sound and light show, as well as fireworks.

Hanal Pixán in Pomuch, Mexico

Situated in the often-overlooked state of Campeche, Pomuch is a tiny town with one of Mexico’s most fascinating and unusual November rituals. During Hanal Pixán, the Mayan name for what many would call Day of the Dead, living relatives unearth the bones of their deceased – who must have been dead for at least three years – before carefully cleaning them one by one, replacing their embroidered shrouds, and placing them in boxes to be displayed in the niches which line Pomuch Cemetery.

Festival de Calaveras in Aguascalientes, Mexico

José Guadalupe Posada, the creator of the Day of the Dead’s most iconic image – a satirical engraving of La Catrina, a skeleton bedecked in colonial finery – was born in Aguascalientes. As such, he’s honoured annually during the week-long Festival de Calaveras (Skull Festival), which brings together live theatrical and musical performances, swathes of visitors bedecked to look like La Catrina, regional foods, and more.

Festival de la Calabiuza in Tonacatepeque, El Salvador

You’d be forgiven for thinking you’d stumbled onto a zombie film set were you to visit Tonacatepeque on 1 November. In actuality, the streams of people painted white with horror-movie make-up or dressed as Central American folklore figures like La Siguanaba and her son Cipitío are celebrating the Calabiuza Festival. Developed out of the trick-or-treat-esque tradition of asking for ayote en miel (sugared pumpkin), the tradition has experienced a resurgence in El Salvador’s post-war years.

Fet Gédé in Port-au-Prince, Haiti

Fete Gédé (or Fhête Ghede), a typically Haitian celebration of deceased ancestors observed by vodouisants across the country, shares a date with Día de Muertos and is often likened to Mardi Gras. One of the biggest and best Fet Gédé festivities takes place in the Port-au-Prince Grand Cimetière, where the living dance, drum, feast and pay homage to the dead at their gravesides

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments