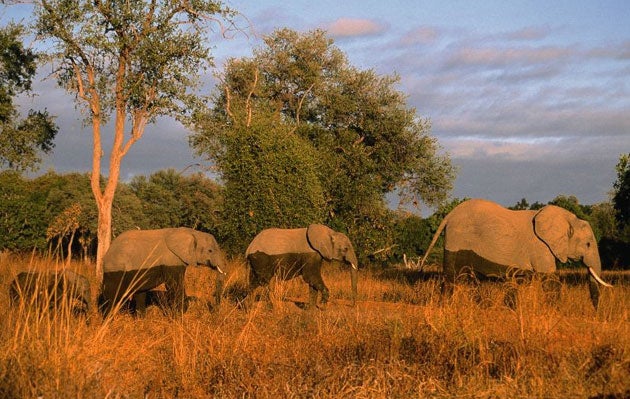

The long march: If you're looking for big game in Zambia, ditch the 4x4 and strike out on foot

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.The trail had gone cold, lost somewhere in a maze of tracks among the purple pan weed. Our guide, Levy, straightened up, wiped his brow and scanned the treeline – but without conviction. It was nearly two hours since we had found the first tell-tale paw print etched in the dust. This, it seemed, was one lion that did not want to be found.

So the pursuit was called off – to an almost audible collective deflation. Lions, after all, are the number one safari goal. And what could be more thrilling than tracking one down on foot here in the wild reaches of Zambia's Lower Zambezi National Park?

The tension had been palpable when we had come upon the tracks in the slanting light of dawn. But as temperatures had risen, so expectations had fallen. Clearly we were the most conspicuous creatures around, our cameras and khakis a mockery of the natural world.

That's the problem with walking safaris. You'd imagine that stepping out from a vehicle would bring you closer to big game than ever before. But, in general, the reverse seemed true: the bush appeared to be emptying at our approach.

And yet, perhaps there was more to this walking lark than tracking down the most celebrated creatures in Africa. We had now travelled some distance from the Zambezi, moving through a tapestry of riverine woodland, acacia scrub and open plains. Back at camp, the river had at least provided a visible connection to the outside world. But here the bush was utterly inscrutable, with no pointers beyond the ancient network of animal trails.

Certainly there was plenty of wildlife here. That much was evident in the spaghetti junction of tracks at our feet: buffalo, hippo, zebra, hyena, warthog – you name it, all had trodden these trails within the past 24 hours.

In a vehicle, Levy had explained, you are divorced from the animals' world: the sight, sound and smell of the metal box on wheels has no place in their evolutionary frame of reference. Step out of it, however, and you enter the fray, to be judged on their terms.

But avoiding us was not difficult. The Zambezi Valley, after all, is a big place. This can be hard to appreciate when zipping on wheels from waterhole to lion kill. But on foot such zipping can take hours – hot, thirsty, uncomfortable hours – with no promise that your quarry will wait for you to show up.

The wildlife, meanwhile, still obeys basic natural laws. Lions, for instance, are thin on the ground: perhaps one pride per 250sq km. Any more would overload the ecosystem. To find them, you have to tramp many kilometres. And in the process, you discover that the place is rough as well as big. Invitingly open plains turn out to be murderously rutted underfoot, while the ground swarms with ants and the trees bristle with thorns.

Three days later, I was once again searching in vain for a big cat. But this time the cat was a leopard and I was 400km to the north-east, in South Luangwa National Park – Africa's walking-safari capital. Now our plucky band stood frozen in the sand of a dry riverbed, straining eyes and ears against the dawn. Scattered tufts of brick-red fur and a bloody drag mark revealed where the predator had been butchering a bushbuck moments earlier, and the uproar of outraged baboons suggested it was still close. But not a glimpse for us.

However, this time I was more philosophical. It felt somehow just as thrilling to have found the killer's calling cards as to have seen the animal itself. Our paths might have crossed; they might not have. It was enough just to have been there, to have shared the terrain and been encircled in the baboons' chorus of fear. We had felt like participants, not mere spectators.

And liberated from the safari agenda – that relentless tick-list of must-sees – I began to relax into a broader appreciation of my surroundings. Even dung became exciting: a civet midden revealed a smorgasbord of fur, ebony seeds and millipede fragments.

My fortnight of tramping around Zambia ended in its largest national park, Kafue, where the southern district – devoid of lodges or roads – rolls out a truly awesome wilderness to the western horizon.

Lions were making a final bid for our attention. We'd heard them calling across the river during the night and found tracks within minutes of setting out. But by now we'd wised up and the prospect of finding the cats was soon eclipsed by the behaviour of a small, ordinary-looking bird.

It was a greater honeyguide, flitting ahead from tree to tree and twittering insistently. It appeared to be guiding us, its agitation rising whenever we veered off course. So we followed, eventually clambering among granite boulders to the foot of a statuesque baobab, where our unlikely pied piper flew into the upper branches and fell silent. And there – high on the trunk – was a hole buzzing with bees.

The honeyguide had earned its name. Our job now was clear: we were required to climb up and haul out the honeycomb, allowing the bird to plunder the grubs from any scraps we left behind. It's a deal this species works with honey badgers – and traditional peoples – all over Africa. But none of us was especially inclined to shin up a baobab and stick our hands into a wild bees' nest.

As we set off back towards the river, the irate bird vented its frustration in a paroxysm of twittering. Next time, according to African folklore, it would get its revenge by leading us to a black mamba.

That evening, watching the sun setting over the unfathomable vastness of Kafue, I realised that I had caught the walking bug. OK, so this time I didn't meet a lion. Perhaps next time I would – I'd certainly heard countless campfire yarns of close encounters.

Yet, I reflected, chasing lions somehow missed the point. On foot, it's not about what you see but how you see it. I had – in my brief, privileged, tourist way – experienced one of the world's most thrilling natural environments from the inside. Afterwards, a game drive felt like watching animals on TV.

Mike Unwin walked from the following camps and lodges: Old Mondoro, Lower Zambezi ( chiawa.com); Chikoko Trails Camps, South Luangwa ( www.remoteafrica.com); Bilimungwe and Kapamba Bush Camps, South Luangwa ( bushcampcompany.com); Kaingu Lodge, Kafue ( kaingu-lodge.com)

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments