Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Deep in the night, I hear a lion roaring, a low melancholy call that carries for miles across the plains. It’s a sound of strength and supremacy as the king of the beasts stakes his territorial claims. But with lions becoming increasingly vulnerable due to poaching, habitat loss, hunting and human-wildlife conflict, it’s a sound that could soon be silenced. Today, just 24,000 lions survive in Africa; experts believe they could be extinct by 2050.

“That was probably Mr T you heard,” our guide Dulla explains in the morning. “He’s letting the other lions in the area know who’s boss.” Named after the dark T-shaped pattern on his mane, we’d encountered Mr T shortly after arriving at Ruaha National Park in southern Tanzania. He was lying in the shade alongside four lionesses of the Mwagusi pride, their bellies full of the buffalo whose carcass, swarming with flies, lay nearby.

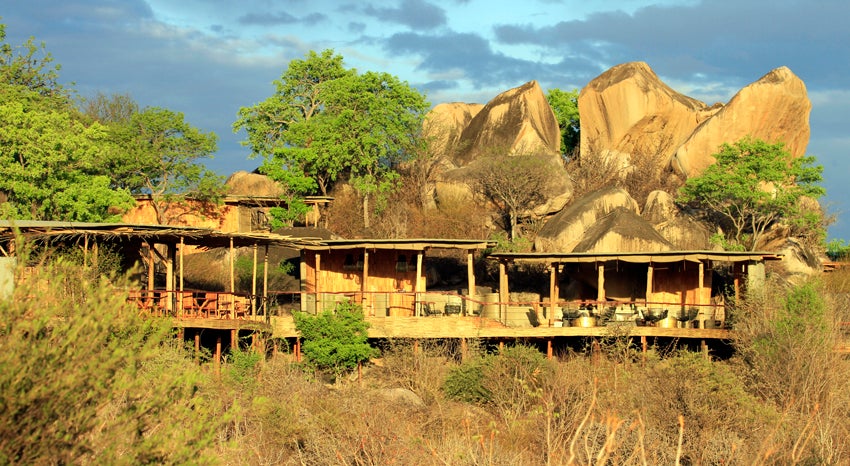

Raw and remote, Ruaha is as wild as it gets in Africa. Spanning 20,000sq kilometres, it’s a sweltering landscape of vast sand rivers, bulbous baobabs and spindly palms that is home to 10 per cent of the continent’s lions. Surprisingly few travellers come here, but Jabali Ridge, Asilia Africa’s new lodge, which opened in September 2017, looks set to lure them, with eight luxury rooms, a gin bar, spa and infinity pool. Asilia supports conservation initiatives throughout Tanzania and Kenya, including Oxford University’s Ruaha Carnivore Project (RCP). I was there to see the fruits of their remarkable work on lion conservation with local tribes.

Kitisi is a sprawling village of mud brick houses along a dusty ochre track – one of 12 benefiting from RCP’s programmes. As pastoralists whose lives are centred on their cattle, the Barabaig and Maasai tribes have a cultural hatred of lions, and kill them during traditional hunts in rites of passage for warriors, or in retaliation for killing livestock. Slowly but surely, however, the age-old tribal mindset is changing: their lion-killing warriors have become predator protectors.

With guidance from Kenya’s Lion Guardian project, RCP began their Lion Defender programme in 2012. “Before we started, around 60 lions a year were being killed by the Barabaig. This year there were just four,” says BenJee Cascio, Lion Defenders manager.

Mandela from Kitisi is one of 13 warriors who has retrained as a lion defender. “I was 18 when I speared my first lion but I’ve realised it’s just too dangerous,” he says. “Being a lion defender encourages us to see other alternatives to hunting, and other benefits. Two of my friends out hunting were killed by elephants recently – where’s the benefit in that?”

Once a secretive, nomadic tribe regarded as outsiders and averse to change, the Barabaig are slowly adapting to new initiatives. Cascio takes us to meet a family learning to live with lions. Their remote homestead has small mud-and-thatch buildings with no running water or electricity, but its cattle enclosure is made of wire fencing rather than the usual bomas (enclosures) made of sticks. Kamunga, an elderly man dressed in traditional purple cloth, was one of the first adopters of RCP’s lion-proof bomas. “It’s a long time since I’ve lost an animal,” he smiles. “The lions and hyena are always circling around and roaring, but they can’t get in.”

To date, lion defenders have helped construct around 150 wire bomas protecting 16,000 animals worth £1.6m (cattle are worth £300 each, goats a mere £14). They’ve also returned some 5,000 lost livestock worth over £500,000 to the villages. They track lions, compile GPS data on predator hotspots and warn villagers of their whereabouts. With livestock killings falling by a staggering 60 per cent, they’ve become local heroes.

RCP provides meals in primary schools, funds children through secondary school and university, takes locals into the park and holds wildlife DVD screenings to over 30,000 people. Aiming to link social benefits to conservation, the company has also created an innovative competition based around cameras they’ve set up in villages which track wildlife going in and out. They award points per animal spotted, which convert into benefits including healthcare, education and veterinary materials – along with celebratory parties.

These parties give RCP’s Community Liaison Officer Stefano Asecheka the chance to engage with young people about health and conservation. He was the first Barabaig to work with the project in 2009. “We’re still behind the times but there’s a gradual cultural shift giving us alternatives to our traditional lifestyle,” he explains. “I introduce conservation principles to our communities and help RCP understand our culture.”

But ancient cultures don’t change overnight and hunts still occur, albeit sporadically. “It’s hard to see a dead lion, helpless, its body full of spear holes,” BenJee tells me. “At those times, we have to put ourselves in the Barabaigs’ shoes and understand their sacrifices. And we have to remind ourselves of our successes too.”

Traditionally, successful hunts would be celebrated. The warriors who’d speared the lion would dance around its paws, tail and teeth, and they would get the kudos, the gifts – and the girls. With communities spread out far and wide, such celebrations provided rare opportunities for young men and women to socialise.

With the unenviable task of dissuading angry young men hell-bent on a hunt, being a lion defender isn’t easy. But with 90 per cent of hunts now successfully prevented, RCP in a clever twist has turned tradition on its head, throwing parties for villages that haven’t had a hunt for a month. Surely a cause for celebration if it means Africa’s lions can still roar loud and proud across the plains.

Travel essentials

Getting there

Expert Africa offers a tailor-made trip with four nights at Jabali Ridge from £3,845pp, including flights and transfers, all safari activities in Ruaha and full board accommodation.

More information

British nationals require a visa to enter Tanzania, which costs £40 and is available from the Tanzania High Commission. An International Certificate of Vaccination for Yellow Fever is also required.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments