‘Father of the internet’ reveals the reasons he fears for its future

Speaking as the internet turns 50, its pioneers say AI could pose a profound risk

The internet is facing a range of threats that could imperil both the technology and the people who use it, according to the people who helped create it.

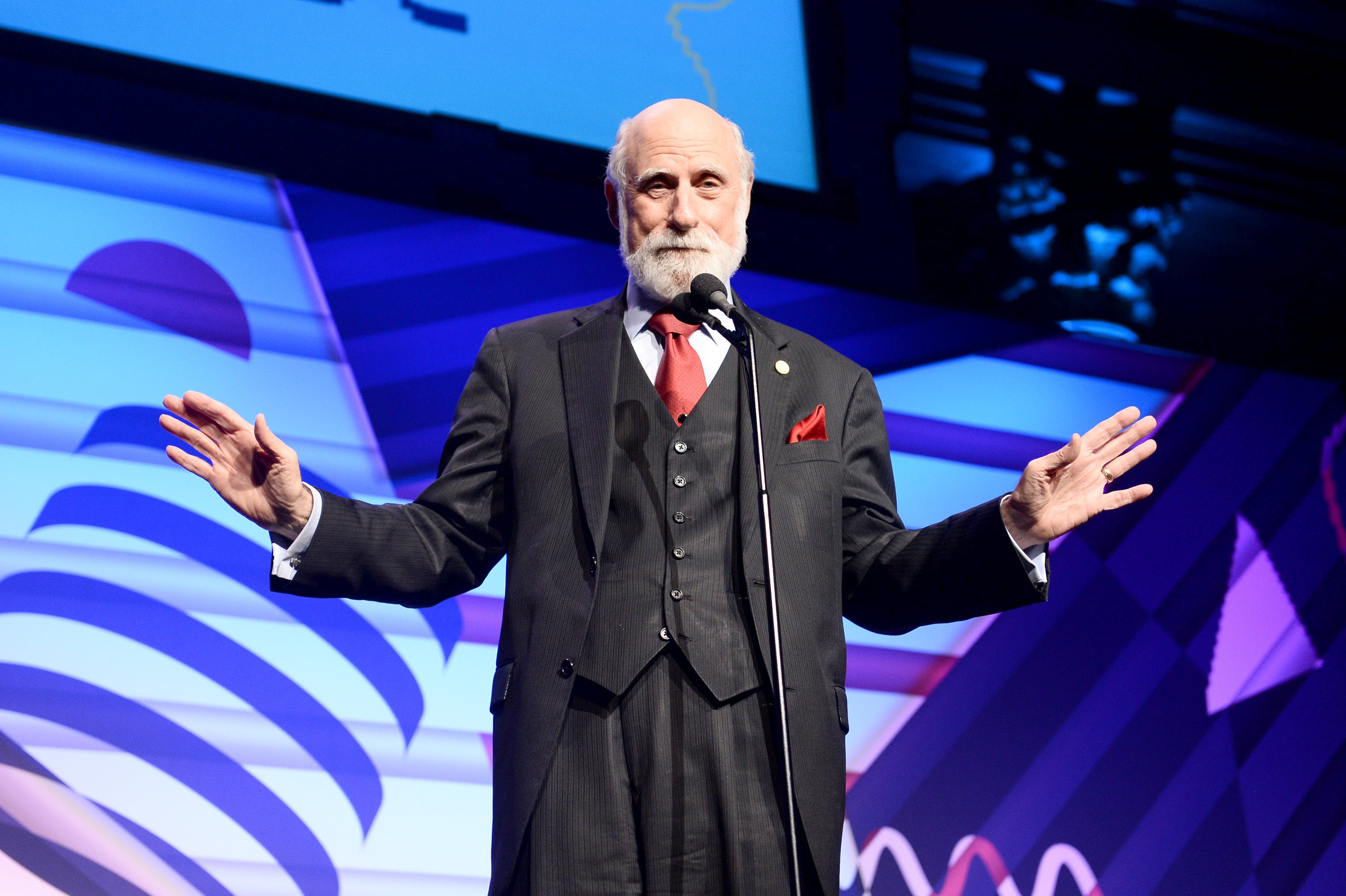

We are becoming increasingly reliant on a technology that is more fragile than we realise and we could be plunged into a “digital dark ages” that will leave us unable to access our own history, warned Vint Cerf, one of the “fathers of the internet”.

The web is also becoming an increasingly central part of our life but that means “there are consequences when it doesn't work as intended” or used by malicious people, he warned. As the internet becomes nearly ubiquitous, it has allowed people to use it for damaging purposes, such as ransomware, he warned.

“The consequences of [the increasing availability of the internet] are that it's accessible to the general public, which it wasn't in its early evolution,” he said. And the consequences of that are that some parts of the general public do not necessarily mean well, and so their access to the technologies enabling, in many ways, very constructive ways, but also in some very disruptive.”

He also warned that there are “a lot of concerns about the reliability and resilience of this technology that we're increasingly dependent on”, and that we were granting increasing autonomy to software to take actions on our behalf that we might not understand.

We rely heavily on our mobiles, for instance, because of their “convenience and utility”. But there may be “no alternative” to use when they break, leaving us with increasingly fragile systems.

He also suggested that fragility runs into the future. None of the digital media that we have today has lasted anything like as long as the paper that we previously used – and so we might no longer be able to access the files that make up our understanding of our history.

“I'm beginning to wonder what what kind of ecosystem would we have to create that would assure everybody that digital content has some serious longevity,” he said. He pointed to the fact that he recently found some floppy discs that included files made only a couple of decades ago that could no longer be read; “It's embarrassing to think that baked clay tablets five or 6000 years ago are still legible,” he said.

Fixing those problems will mean “rethinking our ecosystem writ large”, he said, with new legal structures and international agreements as well as technology to make sure we are able to rely on our digital environment, he said. That might mean writing a new “digital social contract” that calls for people to be more accountable for the way they interact with the world online, for instance.

We should also work to “improve people’s intuition” about how to use technologies safely, and allow them to exert more agency in protecting themselves, he said. “We need some more critical thinking and willingness to think critically, especially about the information that we get”, a problem he said had been exacerbated by the wide availability of large language models.

But he said that he was not as worried about the power of artificial intelligence as some other technologists. While computing had brought “astonishing” new capabilities, much of the panic about AI was the result of “imbuing them with more than they actually are”, in part because it is trained on human text and so often looks as if it is speaking in the same way we do.

Mr Cerf was speaking at a meeting organised by the Royal Society and a range of other organisations to celebrate 50 years of the internet. He said that those early days of internet was often characterised by an optimism about whether the system would be abused.

“When we started doing this work, we were just a bunch of engineers, and we just wanted to make it work enough to get something like of this scope and scale to work,” he said. “And I don't think we were thinking very much about how the system could be abused by people who have your best interest at heart.”

He said that there had been a considerable amount of concern about security, such as encrypting web traffic so that it could not be intercepted as it passed across the internet. But there was less concern about safety, he said – so there was less thought about the fact that traffic could be carrying malware that would attack the computer it was sent to.

“So I think we need to be rethinking the ecosystem that we're creating. It's not this ethereal thing. It has real world consequences,” he said.

“It’s becoming a contested space in the geopolitical sense, where we have real concerns about national security, as well as personal security in the online environments.

“And I can assure you that at the very beginning, that was not at the top of the list. It was just trying to understand what happens if every computer could talk to every other.”

Wendy Hall, a British computer scientist at the University of Southampton who helped build some of the foundational systems of the web, told The Independent during the same event that she was optimistic about the future of the internet.

“The internet – the infrastructure of how computers talk to each other – has been around for 50 years,” she said. “And it’s survived everything, including Covid.”

“We all piled onto it in 2020, and it stayed up and running. And imagine what Covid would have been like without an internet or a web.”

But she agreed that AI could eventually become an issue, pointing to the importance of learning the lessons of the history of the early internet and web. Alongside her other work, Dame Wendy serves on a UN advisory body on artificial intelligence, which is aiming to encourage international governance so that those dangers can be avoided.

“AI is potentially more dangerous” than the web itself, she said. “I’m not someone who says we’ve got an existential threat next year, or in the short term – but if we let AI get out of hand, it’s going to be used by rogue actors.

“If we let AI get out of control, so it does things we can’t control – whatever that is – we have a problem.”

She pointed to the importance of ensuring that the technology is useful for everybody, making sure that the technology is available to those in the global south as well as richer countries, and keeping people safe from rogue AI actors. And she pointed to more far off dangers, which need to be worked on by the defence and security sector, to “keep us safe from potential AI wars in the future”.

But Dame Wendy said she was optimistic about the “tremendous things” that AI could achieve, including “how it will help us with health education, energy supply, food security” and more. She also said that she was hopeful that the world would come together to provide good governance – but that significant work still needed to be done.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks