The big draw: Pixar power

When Pixar gave artists serious computer power, they reinvented cartoons. But just how good can animated films get? Rebecca Armstrong meets the studio's top talent to see for herself

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.In 1997, when Mark Walsh was an eager student graduating from a California arts college course in animation, he was dreaming of a job at Disney. "When I applied, they said you have to work your way up – and that it would take 10 years before I'd do any real drawing," says Walsh, now 32. Fortunately for him, there was another company emerging at the time, and Walsh heard they were hiring. The firm of just 200 was no rival to Disney's vast set-up, but it had one success under its belt and was looking for talent.

"The company was called Pixar," Walsh says. "And if I took the job there, I'd be an animator right away. But there was a problem – Pixar only did computer animation, and I wasn't a computer person. Of course, I took the job, even though it took me about six months to figure out what a computer was." Ten years on, Walsh is now the chief animator at Pixar, the "small company" that Disney bought two years ago for $7.4bn.

Given that Pixar's CEO at the time was Steve Jobs, the force behind Apple, it's hardly surprising that the studio was at the cutting edge of computer animation and has remained there ever since. As anyone who's seen Toy Story, A Bug's Life, Finding Nemo or Monsters Inc knows, the hi-tech revolution has revitalised the animation industry. Not to say that there's much wrong with Snow White, or Bambi, or The Jungle Book; it's just that the new ones are, well, different.

"As computers get faster, it increases what we can do," Walsh says. "One thing is being able to have more detailed backgrounds, which were too expensive to do in Toy Story and A Bug's Life, but which we can now do in every scene."

Computers also mean that Pixar can make its films ultra-realistic. For Monsters Inc, staff set themselves the task of animating each of Sully's three million strands of fur. And this realism will only increase as processing power does.

"Our movies still run at 24 frames per second, but now that we don't use film we could make it 48 or 64 frames a second, and at that speed it will start to look more like reality," Walsh says. "In the future, films will have super-high frame rates so that they will look real."

For most of the last century, animated films were made up of drawings that were photographed and then copied on to transparent acetate sheets called cels, which were painted and then re-photographed individually on to motion-picture film. But since the mid-Nineties, animators' drawings have been either scanned or drawn directly on to a computer screen.

Pixar's first film, the Oscar-winning, $354m-grossing Toy Story, released in 1995, was the first feature-length computer-animated film. But Walsh, who has worked on A Bug's Life, Toy Story 2, Monsters Inc, The Incredibles and Ratatouille, explains that there's a lot more to making a computer-animated film than simply double-clicking on the right icon.

"The phrase 'computer animation' makes it sound as if the computer does all the work. It doesn't. The computer is a tool – basically, a really expensive pencil. It can animate for you if you want something to look like a robot, with everything moving very evenly and then stopping abruptly, but at Pixar, every frame is hand-finished the same way as if we were animating with clay or paper."

What computers do allow Walsh to do is explore artistic avenues that are almost impossible to create on paper. "Computers give me the chance, as an artist, to try things that would be hard for me to draw; small twitches in the eye or the flick of a tongue that are difficult to draw on a small scale, but on a computer are quick."

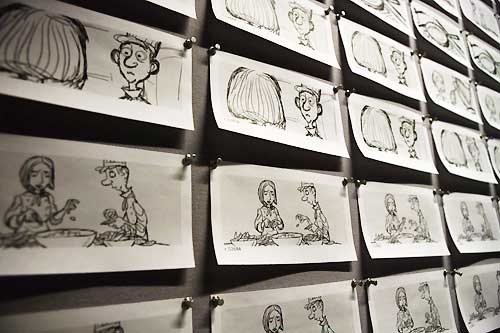

The entire process, however, still required hundreds of specialists. "To begin with, the story is written in script form, then it is turned into a storyboard. After that, we'll cut it together to make a temporary movie. At this stage, it's still very low-tech". The computer is hardly used until the second half of the animation process. "The first half is done the same way it was in 1937 for Snow White – on paper. The computer and virtual-reality models happen after the drawing is done, and a clay sculpture of each character is made, to ensure that it will work in three dimensions," Walsh says.

There are two reasons for still relying on paper and clay – they're fast and cheap. "As soon as you get into animating on computer software, it requires technicians, it requires artists who are specifically talented on a computer – and it requires computers themselves, which are much more expensive than a block of clay or a pencil and paper."

Once the drawings are complete, the actors who lend their voices to cartoon rats and virtual fish record their lines. "The actors are very gracious; they let us videotape them, and some come and meet the animators," Walsh says. This interaction can help the film. "Sometimes you'll use aspects or mannerisms of the actor. Ellen DeGeneres played Dory in Finding Nemo and, while Ellen doesn't look anything like a fish, she does have a shorter upper lip and you can see her teeth when she talks. We used that in her character."

Next, a team of computer-literate people take the drawings and turn them into three-dimensional models in virtual reality. "Technicians will put controls into each model and work out the maths needed to make sure the elbow is in the right place; if it's not, a character's arm will look like it's broken," Walsh says.

Despite working in a creative industry, Walsh and team are careful not to let their imaginations run too wild. "At Pixar, we try to start off everything with reference – even if we're going to be painting a bowl of fruit in the style of Picasso, we'll look at a real bowl of fruit so we have something to base it on. All the movies have extensive research done on them – in the five years it generally takes to make a film, I'd say an entire year is spent researching." For Ratatouille, Walsh spent a year studying the movement and behaviour of rats. He says he now thinks the rodents are "cute. And very intelligent."

He is hugely enthusiastic about the speed at which technology is allowing animation to develop. "Ratatouille is state of the art, but our next film, Wall-E, will be even better. Five years from now, Ratatouille will look as dated to us as Toy Story does now. I find it very inspiring."

One downside is a problem most computer users suffer – hardware and software that's out of date all too soon. "To resurrect the Toy Story characters for the third Toy Story [due in 2010] we had to find an old machine somebody still had," Walsh says. "It was being used as a coffee table. If they hadn't saved it, we'd have lost the original Buzz and Woody animations."

Asked about the best way for young animators to learn the craft, Walsh advises low-tech experimentation first: "I started with notebooks and a pencil, which is the cheapest way to do animation at home." Among programs, Animation Master is a good starting-point; for more advanced artists, Maya is a winner. "But even Flash gives you the experience of creating something that moves."

However, he warns against substituting flashy software for developing your skills. "A lot of people are really excited that so much technology makes things accessible these days. For example, you can record your own music with Home Studio on a Mac. But it doesn't make your song any good; you still have to know how to write a song – or, in animation, to draw a picture. I recommend that would-be animators go out and observe people." Or, indeed, rats.

Pixar, it seems, is limited only by its imagination – and that works pretty fast, too. At a lunch in 1994, when Toy Story was almost complete, four Pixar bigwigs came up with a bunch of ideas and scrawled a few characters on napkins. They were to become A Bug's Life, Monsters Inc, Finding Nemo and Wall-E. The first three each earned hundreds of millions of dollars at the box office.Wall-E looks set to be another hit for the Pixar animators.

Ratatouille is out on DVD on 11 February. Wall-E goes on general release in July

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments