How our Stone Age ancestors tried to colonise western Europe 10,000 years earlier than previously thought

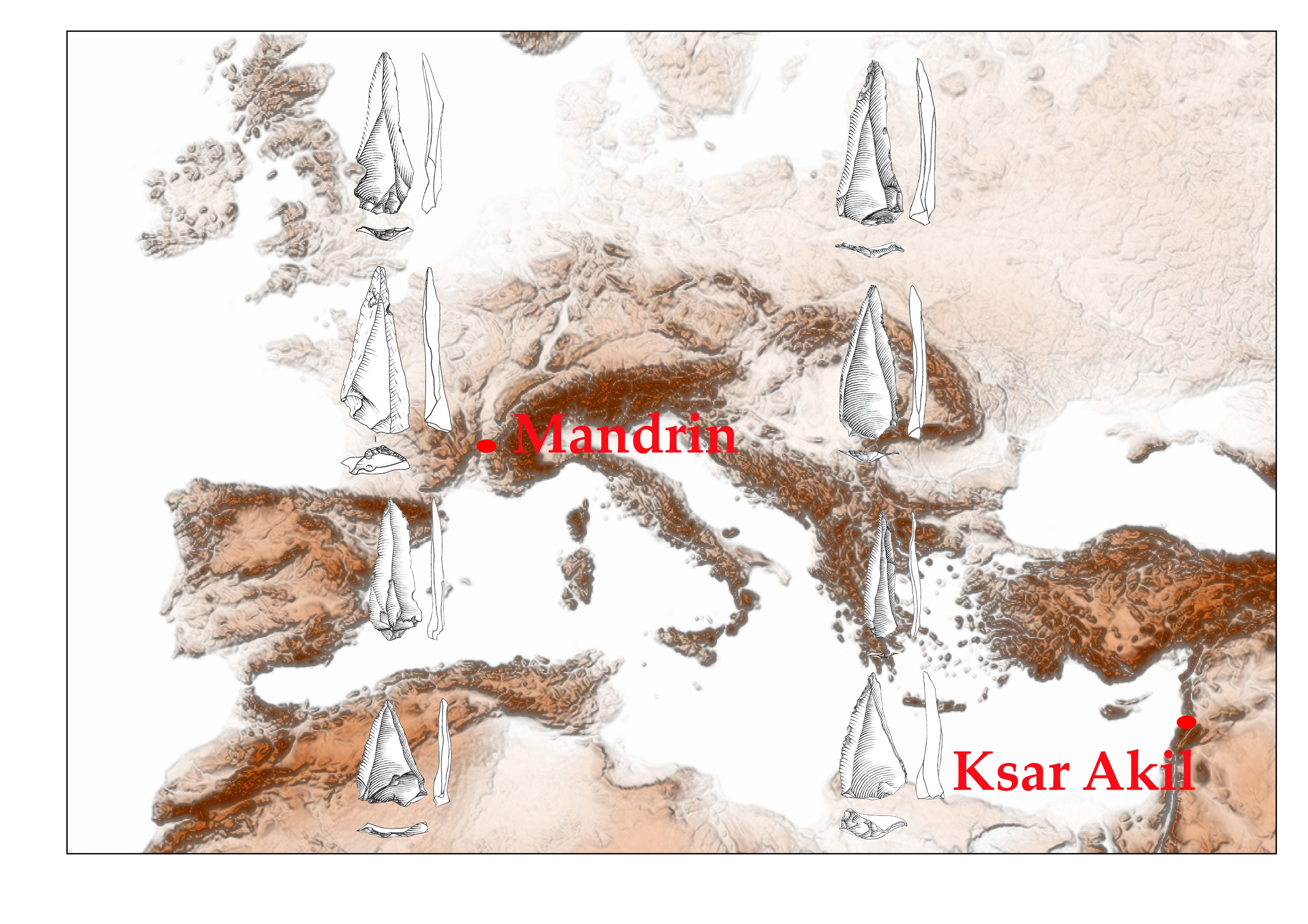

The nature of the flint tool technology found in the cave has led the archaeological investigators to conclude that the colonists or their parents or grandparents had travelled to France from the Middle East

Anatomically modern humans – our species, Homo sapiens – reached western Europe some 10,000 years earlier than previously thought.

But the discovery has also revealed a previously unknown tragic episode in human prehistory.

An international team of archaeologists and other scientists, investigating a cave in southern France, has discovered clear evidence that Homo sapiens reached western Europe 54,000 years ago – but that their attempted colonisation seems to have ended in tragic failure.

The evidence so far suggests that they only succeeded in surviving in the area for around 40 years.

The definitive proof of Homo sapiens’ presence there is a recently analysed child’s tooth found in the cave. Published today by the academic journal, Science Advances, it was found in association with flint tools believed to have been made by Homo sapiens hunters.

Until this remarkable discovery, Homo sapiens activity at this early date was only known from Africa, the Middle East, Southeast Asia, Australia and possibly Greece.

Archaeologists have long been puzzled by the apparent absence of anatomically modern humans (our species, Homo sapiens) in western Europe prior to around 43,000 years ago. But now the new discovery reveals, for the first time, that our species did in fact attempt to colonise the region, but failed (and did not ultimately succeed until some 10,000 years later).

The investigation into what befell the colonists 54,000 years ago is still at an early stage.

At present, all that is known is that Homo sapiens colonists travelled by sea (or by foot along now long-submerged coastal lowlands) from the eastern Mediterranean to the mouth of France’s River Rhône. They then travelled by foot or by raft (or perhaps dugout canoe) some 80 miles up the River Rhône to its confluence with the River Ardèche.

At the time, temperatures at that precise latitude would probably have been too cold for them during the autumn and winter months. It is therefore likely that during those colder times of each year, they lived nearer to the Mediterranean coast. Analysis of material found in the cave suggests that the colonists visited it every year for around 40 years (residing there in the spring and summer).

The archaeological evidence shows that the whole area was mainly inhabited by Neanderthals (a now extinct species of cold-adapted humans). Indeed, the evidence from the cave reveals that Neanderthal humans lived in the cave before Homo sapiens had arrived in the area and after the Homo sapiens’ colonisation had failed.

It is likely that economic competition with the Neanderthals (and possibly even physical hostility from them) was partially responsible for the Homo sapiens colony’s failure. But demographic and climatic factors may also have played a part.

The size of the Homo sapiens colonist population was almost certainly very small – perhaps just a few dozen (or at most a few hundred) individuals, potentially insufficient to guarantee sufficient reproductive success and survival in a climatically harsh and perhaps physically hostile environment.

Additionally, the era in which the colonisation occurred was one of intense and rapid climatic fluctuations – so their ability to compete with the cold-adapted Neanderthals might also have been adversely affected by deteriorating climatic conditions.

The discovery is of huge international importance in four main ways.

First, it brings European prehistory more into line with the prehistory of much of the rest of the world. It shows that anatomically modern humans (our species, Homo sapiens) at least tried to colonise western Europe at a date closer to their well-known colonisation of Asia and Australia.

Second, it shows that the belief that Homo sapiens always triumphed over the Neanderthals is wrong. Ultimately, tens of thousands of years later, they did – but the new evidence from the French cave proves that originally they did not.

Third, the evidence from the cave demonstrates archaeologically for the first time in western Europe that Homo sapiens cohabited an area with Neanderthal humans.

And last but not least, the discovery strongly suggests that Homo sapiens was using sea craft and river craft to carry out their attempted colonisation. This resonates with the already known fact that our species had used seagoing craft to travel between southeast Asian islands and also to reach Australia by around 50,000 years ago (ie very roughly in the same era as the attempted Rhône colonisation 54,000 years ago).

The nature of the flint tool technology found in the cave has led the archaeological investigators to conclude that the colonists or their parents or grandparents had travelled to France from the Middle East – most likely by sea.

“Our ongoing investigations show that the Homo sapiens flint tools in the cave are identical to tools made by Homo sapiens people in what is now Lebanon, Syria and Israel. This suggests that the colonists or their immediate ancestors had originated in the Middle East,” said the archaeological investigation’s lead researcher, the French prehistorian, Dr Ludovic Slimak.

The finds in the French cave mean that archaeologists will now need to fundamentally re-evaluate our species’ interaction with Neanderthal humanity. The dramatic story of how Homo sapiens became the sole surviving human species now appears to have been much more complex than previously thought.

The discovery, published today in the American Association for the Advancement of Science’s Journal, Science Advances, has involved archaeologists and other scientists from more than 20 institutions in eight different countries. Led by Dr Slimak, a CNRS (French National Centre for Scientific Research) Palaeolithic archaeology specialist, based at the University of Toulouse Jean Jaures, the investigation has deployed new cutting-edge techniques to reconstruct a detailed chronology of Neanderthal and Homo sapiens use of the cave, Grotte Mandrin, north of the French city of Avignon.

Three British institutions – London’s Natural History Museum and Oxford and Manchester Universities – have participated in the scientific operation.

“The international team’s research is likely to change the chronological focus of future archaeological investigations into the arrival of our species in western Europe,” said a leading UK Palaeolithic specialist, Dr Alastair Key of the University of Cambridge.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

7Comments