Scientists suggest they have the answer to the mystery of the narwhal's tusk

Gigantic tusks are extended canine teeth full of sensitive nerve endings

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

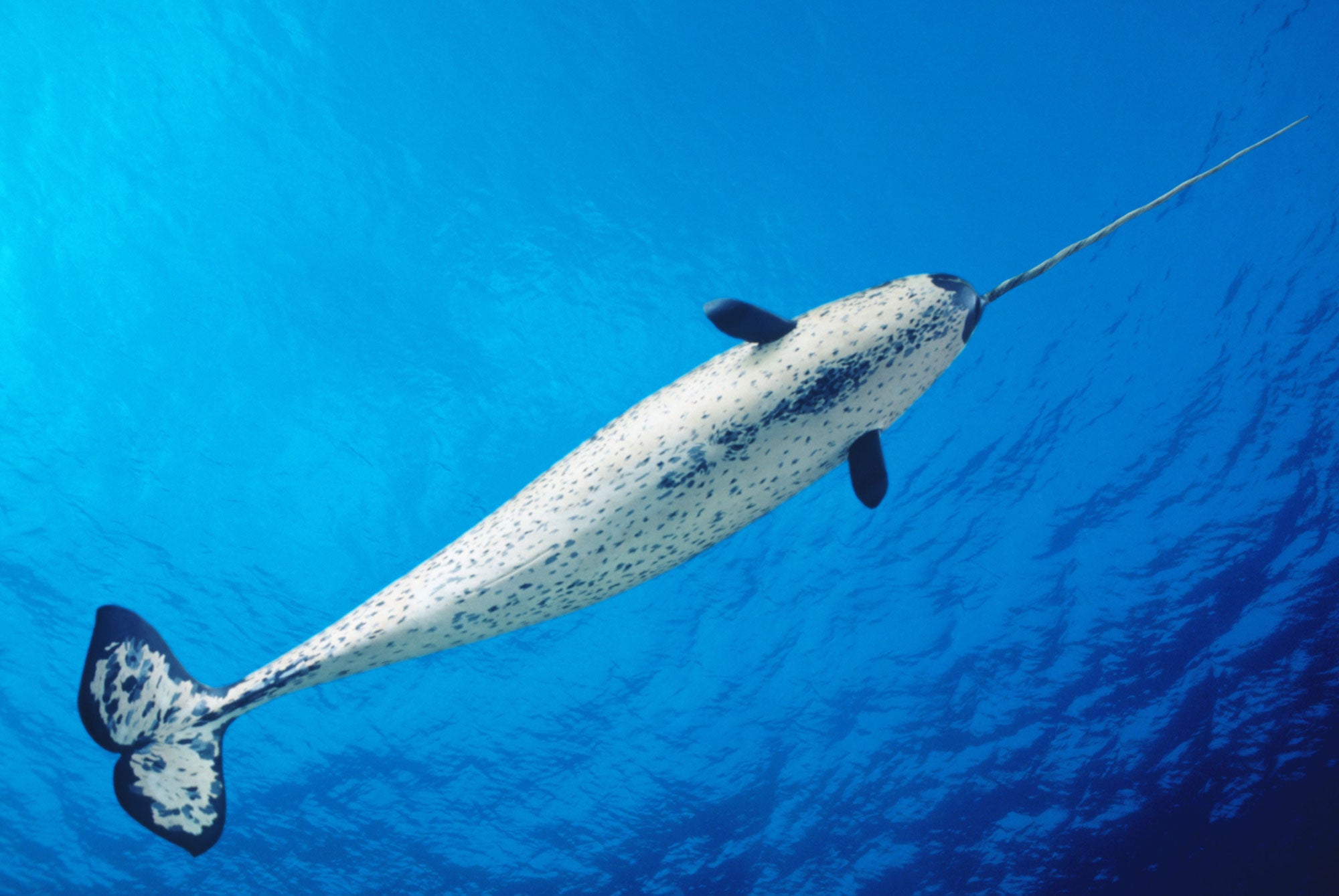

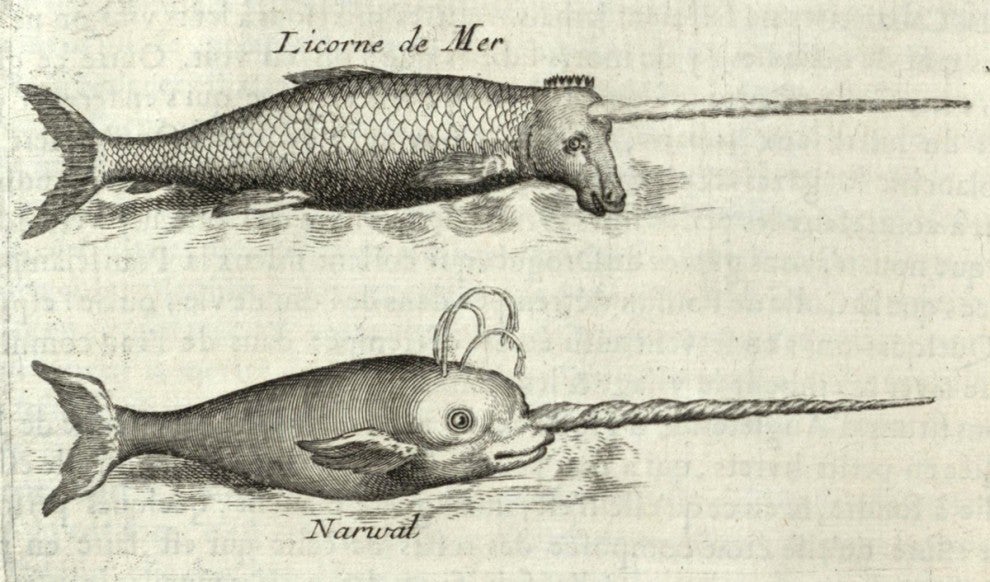

Your support makes all the difference.Narwhals are undoubtedly one of the more bizarre creatures on earth. A secretive species of whale found only in the Arctic Ocean, these animals are best known for their tusks – giant, spiralling protuberances that can grow to nearly nine feet long and are the reason the narwhal was known to previous generations as the ‘unicorn of the sea’.

However, the purpose of this tusk has so far eluded explanation. We know that it is actually a canine tooth that erupts through the lip of male narwhals (though female narwhals occasionally have smaller tusks) and that it always spirals into a left-handed helix, but for a creature that lives in such a harsh environment, the expenditure of so much energy into a useless ornamentation would be bizarre.

Charles Darwin thought that the narwhal's tusk was a secondary sexual characteristic, used to attract mates and establish social hierarchy like a peacocks’ feathers, while other biologists have suggested that it acts as a weapon, letting the narwhal spear prey and duel one another.

Now, a team of scientists from Harvard University led by marine dental specialist Martin Nweeia say they’ve cracked the mystery, and that the tusk is actually a massive sensory organ, used by the whales to measure the salt concentration of water and let the know whether icebergs nearby are melting (low salinity) or forming (high salinity).

Central to this theory is the composition of the tusk. Just like a human tooth, the narwhal's twisted canine is made up of distinct layers, with a permeable outer layer (the cementum) that channels seawater through the tough inner layer (the dentin) to a central, pulp core that's full of nerve endings and blood vessels.

In humans it’s this part of the tooth that reacts to substances like ice cream or coffee, but for us it's shielded by a hard, outer layer of enamel. In narwhals however, the entire design of this enormous tooth is geared towards getting seawater into contact with these nerves – a unique design that has yet to be found anywhere else in the animal kingdom.

Knowing this, Nweeia and his team tested the sensitivity of the tusk to saltwater, netting narwhals and fitting their tusks with a clear plastic 'tusk tube' that they filled with water of varying salinity.

By measuring the animals’ heart-rates they found that the narwhal's heart beats faster in response to high salt concentrations, presumably because this would indicate that the sea was freezing and that the animals were in danger of becoming entrapped by ice. When the liquid in the 'tusk tube' was changed back to freshwater the creatures’ heart rates dropped back down.

Despite this, other scientists have been wary of celebrating the research. Kristin Laidre of the University of Washington told the National Geographic that the scientists’ method of collecting data may have spoiled the experiment; noting that recently-captured animals are likely to have a varying heart-rate simply because they are stressed.

She also added that if the tusk was such an important sensory organ, it didn’t make sense for the females not to grow one too. After all, these are the members of the species that care for the young and so their survival is equally important for narwhal fortunes.

Nweeia himself admits that it's still an "incomplete puzzle" and that the tusk might be an evolutionary throw back instead of an evolved sensory organ. His research is now focusing on traditional knowledge, asking Arctic hunters about their experiences of creature to see if they can shed any light on its behaviour. As an animal that spends most of its time hidden from scientists under the ice cap, it's likely that the narwhal still has more secrets as yet undiscovered.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments