Why can’t sci-fi writers predict the future any more?

Arthur C Clarke, HG Wells and Aldous Huxley were so good at gazing into the crystal ball... so has the future already been written or do current authors lack the edge in a rapidly innovating world, asks Steven Cutts

For a lot of people, science fiction is about a lot more than hi-tech adventure. It is a conscious attempt at foresight, a way to anticipate the risks and joys of the life that awaits us. Aside from the quality of their writing and pace of tier narratives, it’s possible to judge a sci-fi writer by their ability to foresee the things that are yet to come, and at least some of them were really very good at it.

As far as prediction goes, there are two types of sci-fi writers. Those who are really good at it and those who aren’t very good at it at all, but are good at copying. Quite a few of the first group were British, with HG Wells being a credible candidate for the best of them all. In the early years of the 20th century, Wells managed to knock out so many groundbreaking novels that seems to have defined about half of the major science fiction concepts yet plundered by the movies.

Last year saw the release of another televised version of Aldous Huxley’s masterpiece, Brave New World. Exactly how faithful to the actual novel this new and entirely American production has been is a matter of opinion, but if you find yourself baulking at the sheer ambition of the series, try to remember this: the source document was written in 1931. Brave New World predates not only the publication of 1984 but the whole of the Second World War. In fact, if we look at any attempts that have been made to televise Brave New World, the thing that hits you the hardest is that there is simply nothing the actors, art directors and modern day screenwriters can do that competes with the original concept.

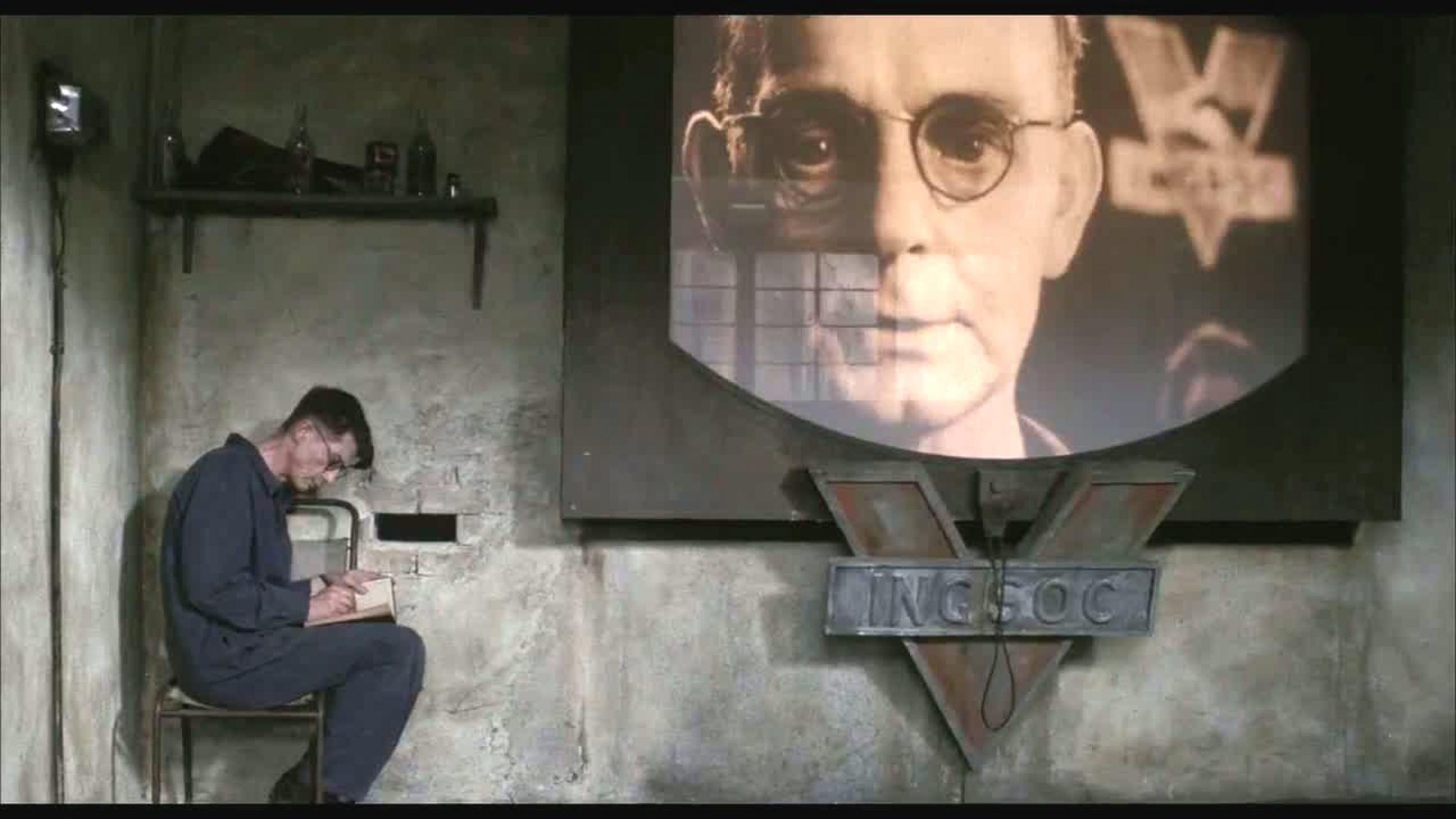

As visionaries go, Huxley wasn’t ordinary. He was frightening. To the scientifically literate among us, the date on the dustjacket reads like a misprint. It is 50 years ahead of its time. It is as if we have wandered into a kindergarten and found a three-year-old child who can play the lead violin for the London Philharmonic. In a mere 64,000 words, Huxley invented an entirely new branch of science fiction, one that the world of film and television continues to exploit. As a school master at Eton, he had already influenced another posh boy, Eric Arthur Blair, who would later write under the pen name George Orwell, and between them these two writers would establish the ground rules for dystopian science fiction that very few have yet been willing to challenge.

But Orwell died young and, like Huxley, his writing covered more than one field. Even his darkest creation – 1984 – is as much a literary novel as it is sci-fi. After the Second World War a generation came of age that simply expected rapid technological development and found themselves exhilarated by all that it meant.

If you watch the Danny Boyle version of Steve Jobs there’s a notable black and white prologue where Arthur C Clarke chats to a television crew and predicts the future. The sequence dates back to the early 1970s and Clarke hits the nail on the head with such precision that he actually makes you feel uncomfortable. He has successfully anticipated the whole of the internet, email and portable devices. As a teenager, I used to talk a lot about computers and telephone lines and how someday the two of them would be interlinked and enable us to change our lives. Most of the kids around me just didn’t buy into this kind of thing. The idea that millions of people might chose to work from home on a laptop was simply too fantastical and at first sight I guess I was something of a visionary. Looking back, I just read a lot of books by Arthur C Clarke as a 12-year-old and remembered what he said.

Clarke was the sort of man who erred on the side of optimism. Futurism isn’t just about predicting the future, it’s about other things too. For a lot of writers, it’s about some desperate nightmare they can’t get out of their head and they want to warn the world about an evil that is yet to come.

Some years ago, I had a staunchly Catholic friend who wanted to write a knockout sci-fi vision of the future with a topical theme. The novel would discuss a future where overpopulation had robbed the Earth of all remaining natural resources and mass starvation was about to set in. Ambushed in the course of confession, he admitted the entire story line to his parish priest and received a predictable scalding from on high. The Catholic church has long been keen on big families and it was never going to stand for the suggestion that their own policies might cause disaster for mankind. I suggested using a pen name and not telling the clergy what he was actually doing, but that wasn’t good enough. He couldn’t be certain that God wouldn’t find out and a few days down the line, he found himself forced to press “select all" and “delete” on the best part of 150,000 words. Doubtless he’s still out there, writing about an army of Ian Paisley clones trying to take over the White House.

Which is interesting because it reminds us that there are all kinds of factors that can distort a writer’s ability to predict the future. One major error for the sci-fi writer is being too obsessed with what is happening today. During the 1950s, atomic power was all the rage and almost every sci-fi writer on the planet described a future that was powered by the atom. Later on, when Green politics took off, they started to play down the atom thing and place more emphasis on the luddite view that in the end, no good can ever come out of progress. No matter how much our material wealth might increase, the fumes and the dust that come with it will soon overwhelm us and we’ll all be desperate to go and live in an oil painting by Constable. Later on, DNA entered the fray and references to DNA were splattered over almost every sci-fi manuscript on the planet. After a while they got boring and the sci-fi writers seemed to go back to AI and killer robots from whence they had once come. Killer robots make for good onscreen action and there’s a reasonable opportunity for the film-related merchandise. In many ways, the arrival of the present has facilitated this reversion to AI. Computers are advancing so rapidly that most of us are practically expecting a robot insurrection and the writer doesn’t have to waste time on elaborate exposition.

Sadly, no matter how hard they try to look forwards, most modern writers are looking backwards. To come up with an entirely new, thought-provoking sci-fi concept is far beyond them. Not so the writings of HG Wells, which were absolutely littered with new and original story lines. What’s changed is the interpretation and the icing on the cake. When Wells first sat down to write TheWar of the Worlds it may well have been an allegory of colonial conquest, but when Hollywood approached it in the early 1950s, it soon became an allegory for Reds under the bed and a collective anxiety that the American scientists might be about to lose their technological edge.

“All our weapons are useless.” Or are they? In Wells’ vision of the future, most but not all of our weapons were useless in the fight against the all-conquering Martians. For others, the situation can get a lot darker than that. To a certain extent, it always seemed to me that it depended more on the personality of the writer. To the American novelist Philip K Dick, the future is always a glass that is half empty but to a man like Arthur C Clarke it is always half full. Picking up where Huxley and Orwell broke off, Clarke’s vision of the future is usually upbeat. In Arthur’s book, any sufficiently advanced technology is indistinguishable from magic to a less advanced society. But Dick was different. Dick seemed to preach caution and in some respects, this probably made for a better read. Let’s face it, your central character has to have something to fight against and if all the problems in the world have already been solved, what will he have to do all day?

This isn’t just about science, it’s about fiction too. We’re trying to shift some copies here.

Remember that drama is based on conflict and a future that is devoid of conflict is hardly fertile breeding ground for fast-paced action. There has to be something to worry about.

And for a lot of writers, worrying seems to be the main motive for writing. Some of the authors are arts graduates that never got on with the science crowd at university. Realising that their own degrees were unlikely to lead to secure jobs, they decided to get their own back by rubbishing everything that science has ever done and predicting death and disaster as soon as some dreadfully clever new bit of kit is unveiled to the public.

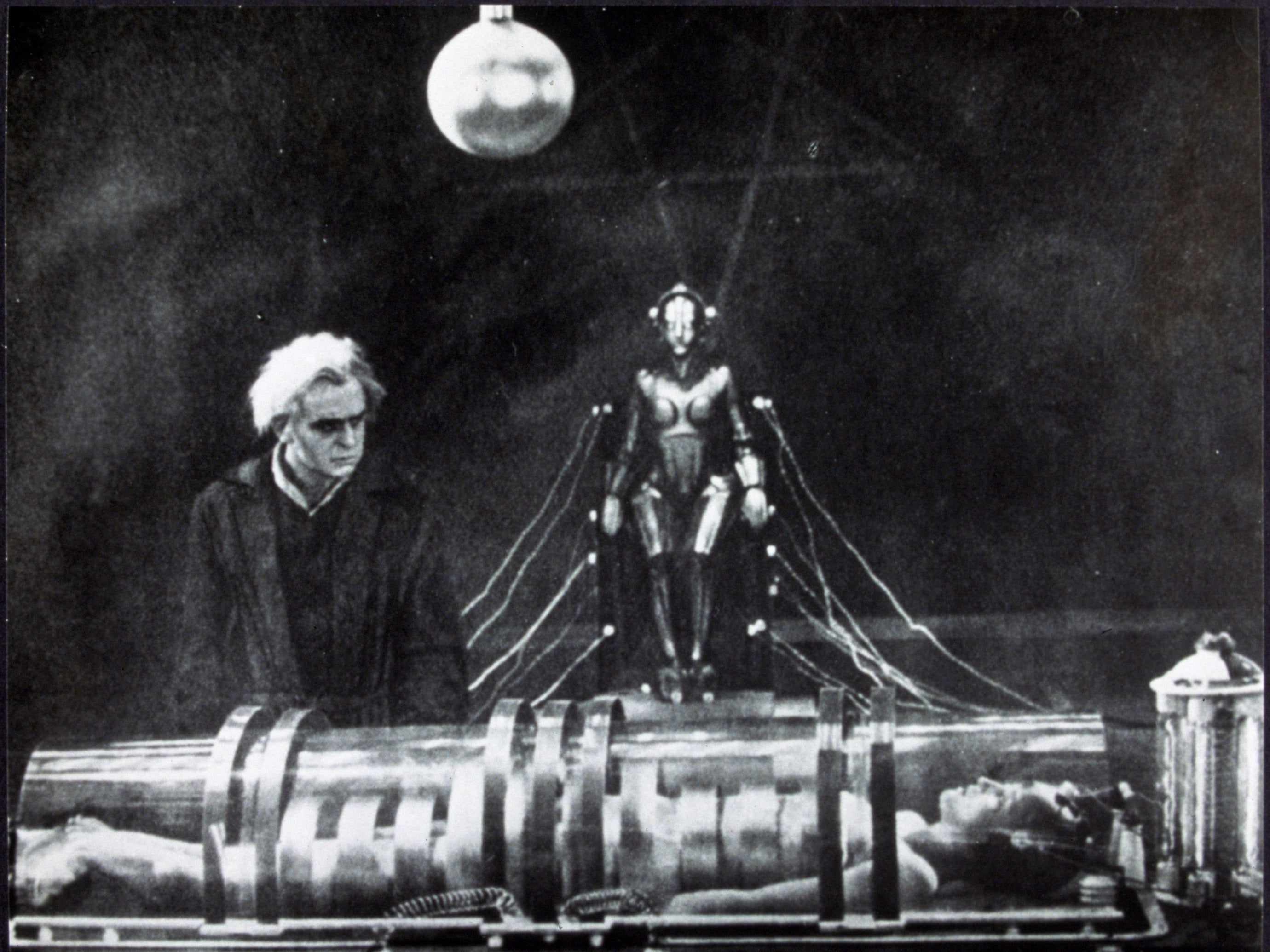

When Fritz Lang made his landmark sci-fi masterpiece Metropolis, it was the most expensive movie ever produced although interestingly it was heavily reliant on flashcards (Metropolis predates recorded sound). A true visionary, Lang was able to portray one of the first human-like robots on screen and even got as far as turning his gadget into a living, breathing woman before the final reel. How the heck did Lang and his friends think of turning the robot into a sentient being? Well, I guess there is Pinocchio, Frankenstein and probably quite a few other sources for him to fall back on but it’s still ahead of its time.

But Metropolis reveals a fundamental problem with sci-fi as a visual medium. The visual side of things ages much faster than the concepts. If you look at colour paintings from the 1950s you can see a vision of rockets that were expected to explore outer space, you can almost always guess the date of its creation, just by glancing at the art. No matter how good the art design ever gets, our love of the present is impossible to shake off.

Slavery and class warfare are still integral parts of our collective consciousness, even though you can be forgiven for thinking that it’s largely a thing of the past. Doubtless this sort of thing will crop up again in the future so we might as well watch a movie like Blade Runner. From a scientific perspective, it doesn’t really make any sense. A society so advanced that it could genetically engineer its own people would be unlikely to require an organic workforce and all the problems that come with them. They could build industrial robots to perform almost any task at hand and with this in mind, quite a lot of sci-fi novelists have gone down the luddite path and predicted a future where the weak and undesirable are forced out of the ballroom and asked to do the dirty work.

Again, this is unlikely to happen. Think about it. As a kid, I caught my first glimpse of Gordon Gecko on an empty beach, calling his friend with a hefty 1980s cell phone. I remember thinking that that one implement did more to convey his prosperity than any of the other visuals in the film. Cell phones were a new thing and in some respects a recognised marker of excessive wealth. Now there are more mobile phones in Britain than there are people and – somehow – they have become the visual motif of the chav, the kind of implement that many of us might choose to ignore in polite conversation. By its very nature, modern tech has become accessible.

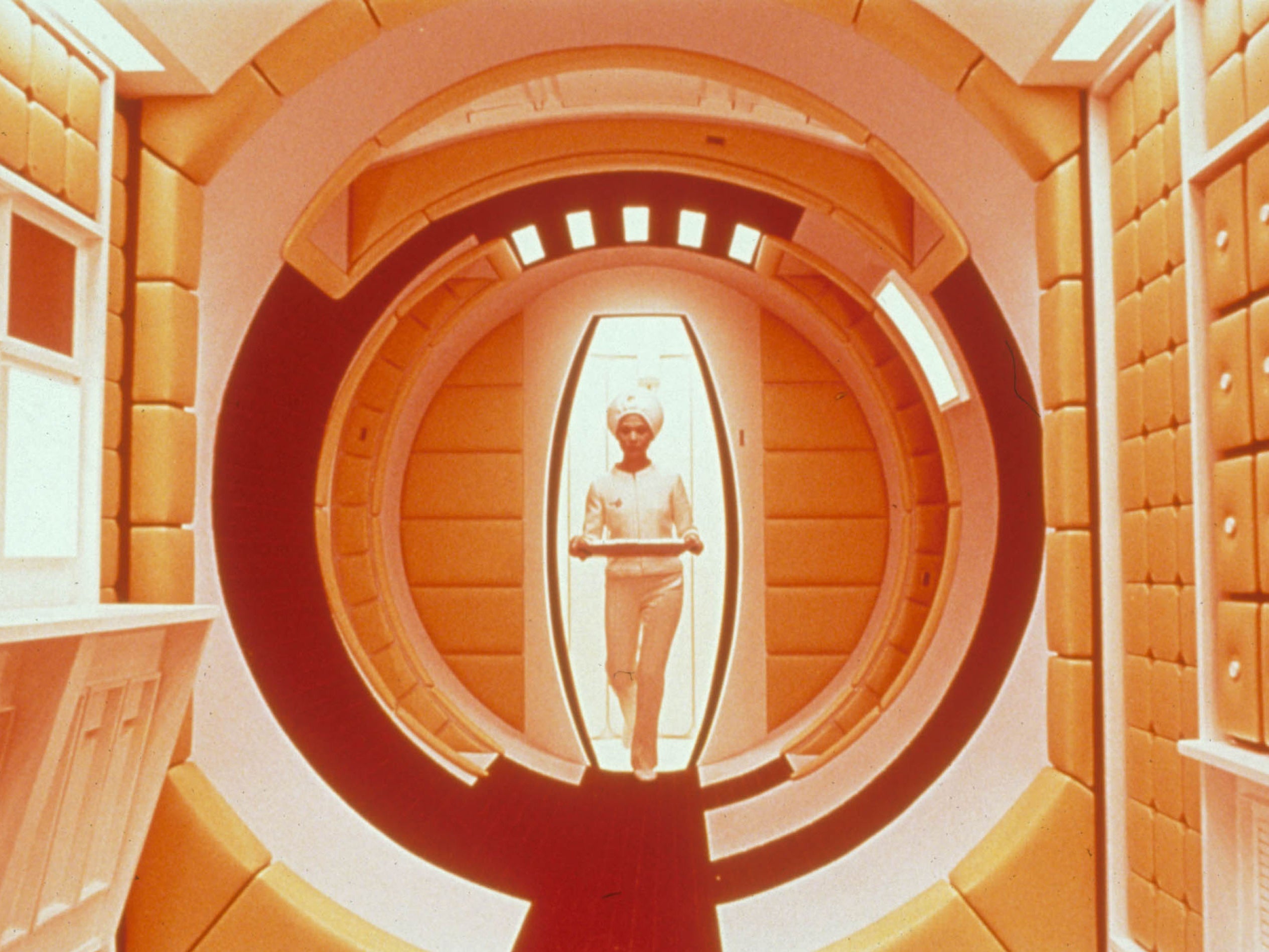

At times, even the likes of Stanley Kubrick and Clarke get it wrong. In the world of 2001: A Space Odyssey, HAL is an iconic player. When astronaut David Bowman goes to turn him off, his electrical circuits seem to occupy half the volume of the ship. If anything, he is a zero-gravity mainframe transported 30 years into the then future. By the late 1960s, computers had become quite grandiose objects, often occupying a remote and spacious building. Both the writers and the set designers were unable to envisage a future in which the all important, godlike character of HAL could be contained in the breast pocket of a human being. The mindset of the present overrided their vision of the future as, I suspect, it so often does today.

The likes of HG Wells were good at prediction. Brian Aldiss would later describe Wells as the Shakespeare of Science Fiction. His record is so good that he’s almost impossible to beat and the big question is – how the heck did he manage all that? Well, besides from being very clever, quite a few of the top science fiction writers turn out to have a formal scientific education. It’s worth mentioning that Arthur C Clarke got a first class degree in physics from King’s College London. Huxley taught at Eton and his half-brother would later win the Nobel Prize for Physiology. Although Wells had a difficult childhood and is largely self taught, he would go on to study biology at the Royal School of Science.

In our own era, Michael Crichton – whose work would later influence our own generation – studied medicine at Harvard and managed to come up with one idea that was so strong that he was able to recycle it again and again. Crichton had a reasonably convincing impact on the world of modern sci-fi, but the suggestion that he was as good or as original as Huxley, Wells or Clarke is hopelessly naive.

Has it all been done already? Or do our current writers just lack the edge? Are they being stifled by some kind of alternative political correctness, or are they being simply outpaced by the frantic speed of innovation in the real world?

We start to see one of the fundamental differences between the true visionaries of the sci-fi world and the people who are just ordinary. Ordinary people look at the world around them and try to find what is new and what is current. When they brave to describe the future, it usually turns out to be more or less the same as it is now. If you look at some of the lower budget episodes of Doctor Who, the set designers have usually found a bit of kit that seemed high-tech at the time and wrapped it in silver baking foil. Later on, they may attach it to a collapsible plastic pipe. Readers who are old enough to remember the Eighties may remember a whole host of futuristic dramas that were commissioned by the BBC. Most of the characters were bored and unemployed. The crimes of the Thatcher years would surely be eternal and our suffering would never end. Many years later, the future arrived and it turned out that there were more people in work than ever before. Be warned, the future doesn’t have to be a linear extrapolation of the past, it could be something completely different.

Steven Cutts is a science fiction writer. His novel ‘The Village on Mars’ is available on Amazon

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks