Scientists discover shape-shifting material that could revolutionise robotics

When triggered the smart material can change its shape by up to 10 per cent

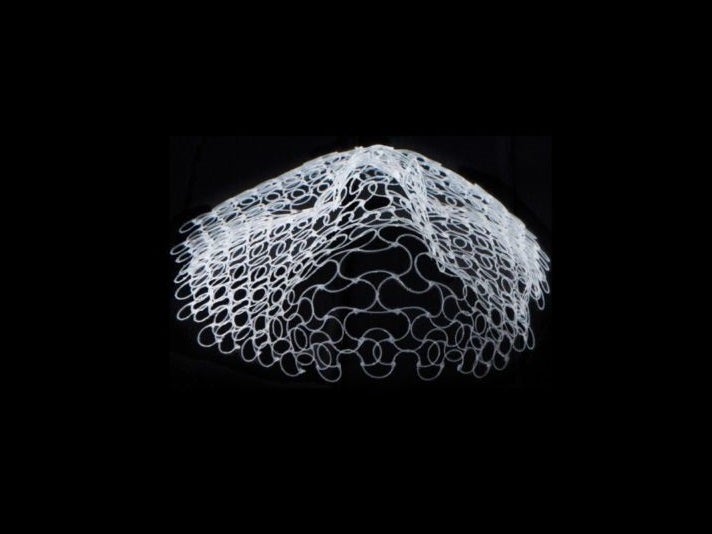

Engineers have discovered a new kind of shape-shifting memory material that they claim could transform everything from jet engines to robotics.

A team from Massachusetts Institute of Technology created the “smart material” using a special type of ceramic, which can withstand vast temperatures and intense wear and tear.

When triggered – either by temperature, mechanical stress, or electric or magnetic fields – the material can change its shape by up to 10 per cent.

Shape-memory materials made of metal have previously been developed, however their applications remain limited in high-temperature settings and at micro scales.

“The shape-memory materials that are out there in the world, they’re all metal,” said Professor Christopher Shuh from MIT’s Department of Materials Science and Engineering.

“When you change a material’s shape down at the atomic level, there’s a whole lot of damage that can be created. Atoms have to reshuffle and change their structure. And as atoms are moving and reshuffling, it’s sort of easy to get them in the wrong spots and create defects and damage the material, which leads them to fatigue and eventually fall apart.”

In order to create the shape-shifting ceramic, the researchers used “all the modern tools of science”, including computational thermodynamics, phase transformation physics, crystallographic calculations and machine learning.

Practical applications remain a way off, though the researchers claim the potential for a micro scale piston is vast.

“It’s very hard to scale down a hydraulic piston, it’s hard to make on the micro scale,” said Professor Schuh.

“[But] the idea that you have a solid-state version of that at very small scales – I’ve always felt there are a lot of applications for microscale motions. Microrobots in small places, lab-on-a-chip valves, lots of small things that need actuation could benefit from smart wearables like this.”

Details of the new material were published in the scientific journal Nature on Wednesday.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

0Comments