Robert Solow: Nobel Prize-winning economist who linked tech advances to growth dies aged 99

His work laid groundwork for understanding how technology accounted for economic growth

Robert Solow, a Nobel laurete who won the prestigious prize in 1987 for his work analysing how technological growth drives economics in developed nations, has died on Thursday at his home in Massachusetts. He was 99.

Solow taught at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) and the economic analysis approach he pioneered along with fellow Nobel laureate Paul A Samuelson has emerged as an important tool in policymaking.

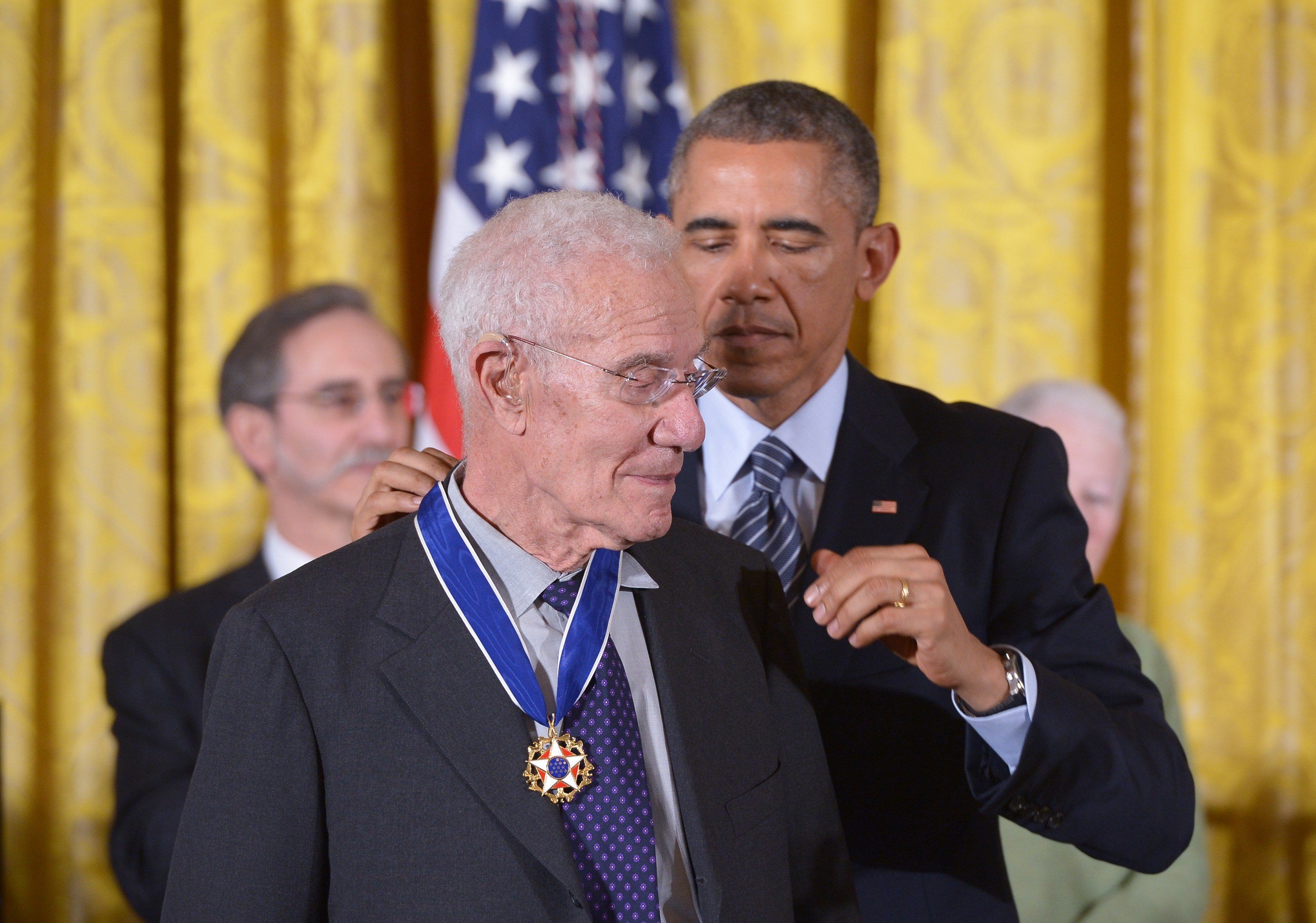

He received a number of prestigious awards, including the John Bates Clark Medal as the finest American economist under 40 in 1961, the National Medal of Science in 1999, and the Presidential Medal of Freedom from Barack Obama in 2014.

Studies into how already developed countries can continue to grow both in terms of production and welfare standards have been central to the work of economists for many years.

In the 1950s, Solow developed a mathematical model illustrating how various factors contribute to sustained national economic growth.

His Nobel prize-winning work yielded a significant mathematical tool for economies to expand production, and led to the development of a field known as growth accounting.

The American economist’s mathematical model describes how increased capital stock in a country generates greater per capita production.

“Solow’s growth model constitutes a framework within which modern macroeconomic theory can be structured,” said the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences, which awards the Nobel prize, adding that his model “had an enormous impact on economic analysis.”

“The interesting thing that came out of my work was that the change in technology – the progress of science, engineering and technology – accounted for half, at least, of all the growth we had in the economy,” he told the Chicago Tribune in 1987.

Prior to Dr Solow’s Nobel prize winning theory, it was thought that increases in capital and labour played the main roles in the growth rate of developed economies.

His work laid the groundwork for better understanding how technology accounted for economic growth in the US, finding that technical progress accounted for as much as 80 per cent of 20th-century American growth.

“I discovered to my great surprise that the main source of growth was not capital investment but technological change,” Solow said in a 2009 interview.

The Nobel laurete’s body of research has helped persuade governments to channel funds into technological research and development to boost economic growth.

Solow was born in Brooklyn, New York, on 23 August 1924 as the first of three children.

He attended public schools in New York City and served in the US Army during the Second World War, returning to earn an undergraduate degree in 1947, followed by a master’s degree and PhD by 1951, all from Harvard University.

Solow then spent his career teaching statistics and econometrics.

“I was given the office next to Paul Samuelson’s. Thus began what is now almost 40 years of almost daily conversations about economics, politics, our children, cabbages and kings,” the Nobel laureate wrote in a biography.

He is survived by his two sons, a daughter, eight grandchildren, and three great-grandchildren, according to the New York Times.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

0Comments