Planet that rains rocks and has winds faster than the speed of sound discovered by scientists

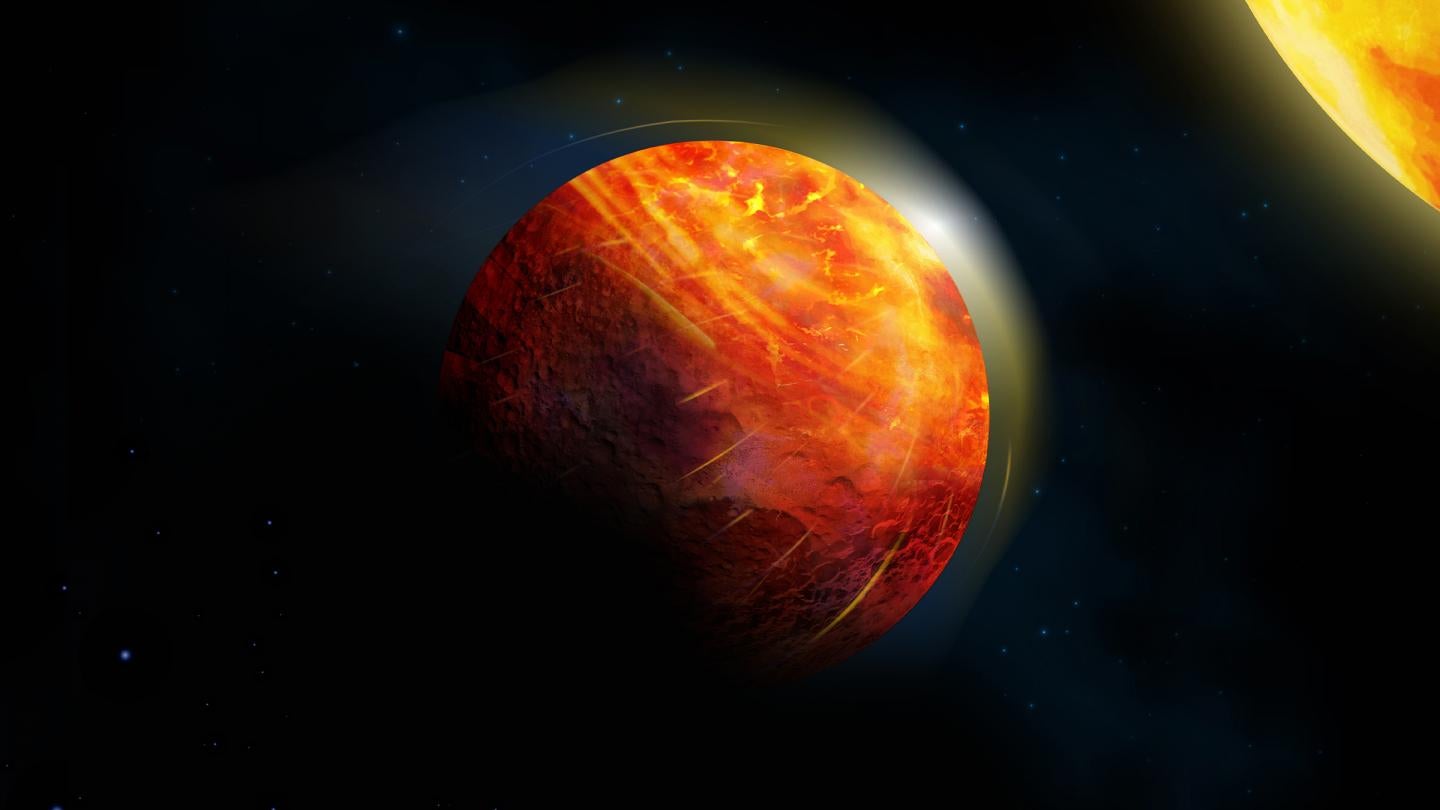

Scientists have found a planet where it rains rocks, the winds whip faster than the speed of sound and there is an ocean of magma more than 100km deep.

Researchers have found extreme “lava planets” before. They are worlds so close to their host star that the surface is made of oceans of molten lava.

But the newly-analysed planet known as K2-141b is unusual even among those extreme worlds. Its surface, ocean and atmosphere are all made up of rocks, which fall like rain and melt into its huge seas.

Two thirds of the planet is stuck in perpetual, blazing daylight from the orange dwarf star that K2-141b orbits around. Because it is so close to its sun – with years that last less than a third of a day on Earth – it is locked in place gravitationally, meaning the same side of the planet always faces its star.

On the dark side, temperatures are less than -200 degrees C. On the other, daylight side, it is about 3000 degrees C, hot enough to vaporise rocks into a thin atmosphere.

It’s that atmosphere that undergoes precipitation, working on similar principles to rainfall on Earth. Just as water evaporates into the atmosphere and then falls back down as rain before beginning again, so does the sodium, silicon monoxide, and silicon dioxide on K2-141b, with the rocky atmosphere being pulled across to the night side by supersonic winds and allow it to drop back down to the surface.

Researchers used computer simulations to understand what conditions might be like on the planet, which is roughly the same size as Earth but much closer to its Sun. The planet is more than 200 lightyears away, and was discovered in 2018.

Researchers used existing data about the world and analysed it using computer simulations that let them understand what the planet’s atmosphere and weather cycle could be like. Their findings could be tested in the future by new technology that will allow much more detailed observations of the atmosphere and composition of distant planets.

"The study is the first to make predictions about weather conditions on K2-141b that can be detected from hundreds of light years away with next-generation telescopes such as the James Webb Space Telescope," said lead author Giang Nguyen, a PhD student at York University.

The findings are reported in a paper, ‘Modelling the atmosphere of lava planet K2-141b: implications for low and high resolution spectroscopy’, published in the journal Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

0Comments