One man hears Wi-Fi wherever he walks

Despite going deaf, Frank Swain can hear something other people can't

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.A man who is going deaf can now 'hear' Wi-Fi wherever he walks.

London-based science writer Frank Swain, 32, was first diagnosed with early onset hearing loss when he was in his 20s. In 2012, he was fitted with hearing aids.

Mr Swain says he was inspired to hack his hearing aids from the first day he received the devices.

Two years later, and after receiving a grant from UK innovation charity Nesta, Mr Swain and sound artist Daniel Jones have produced Phantom Terrains, a new tool that makes Wi-Fi signals audible.

The tool runs on Mr Swain's iPhone and picks up details about nearby signals, such as the router name, signal strength and distance.

Each detail is given its own sonic tone which are streamed to his phone and picked up by a special pair of Bluetooth-connected hearing aids. It means Mr Swain will always be able to hear Wi-Fi as long as he carries his phone with him.

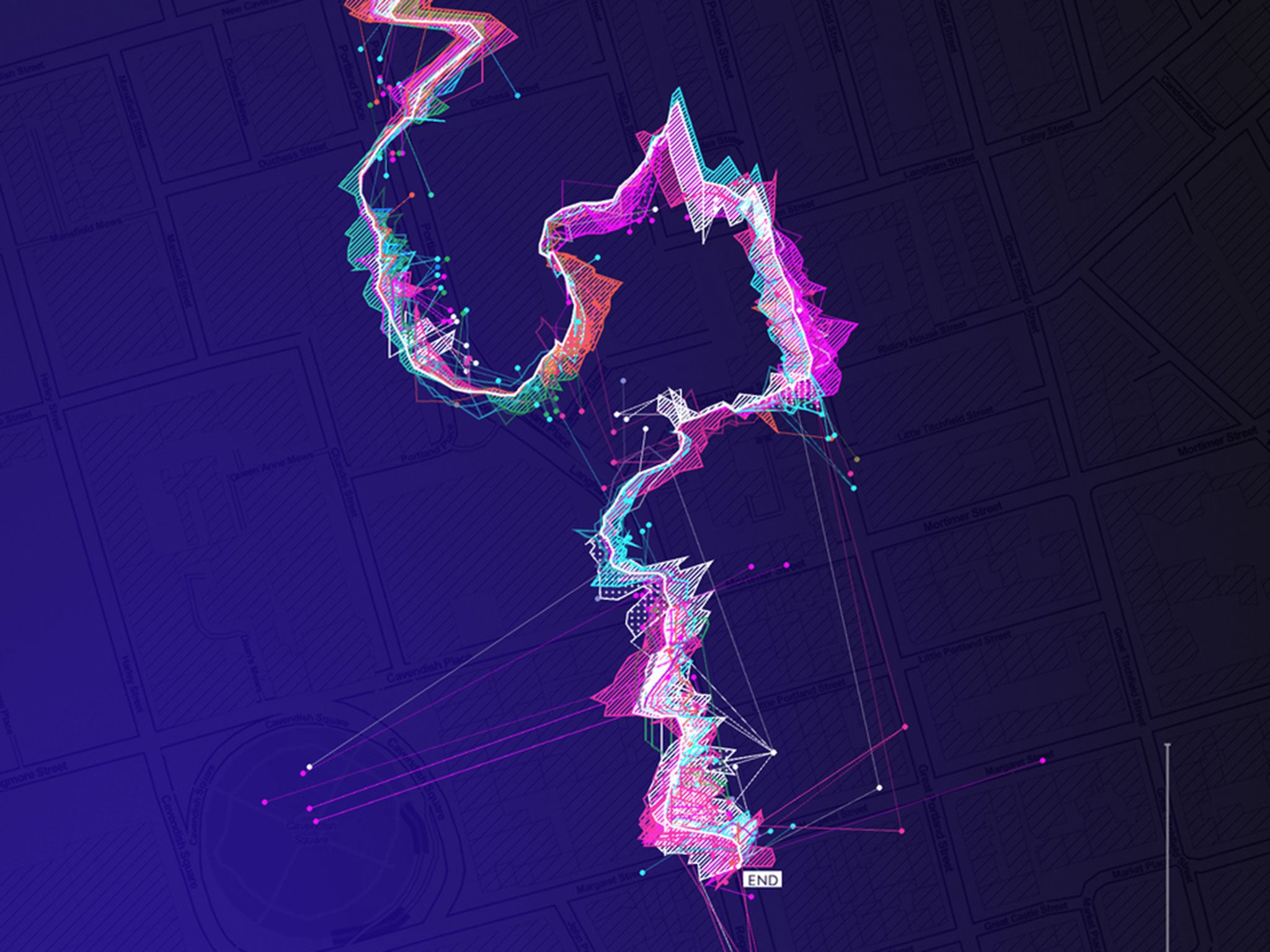

Mr Swain produced a map and audio to demonstrate what the internet sounds like from his walk around the BBC Broadcasting House in central London .

Speaking to The Independent, Mr Swain explained: "The information is turned into sound on the phone. Distant signals are rendered as clicking beacons like a Geiger counter, whilst the strongest signals have their network ID turned into a looped melody.

"This audio is then streamed wirelessly over a Bluetooth connection to a pair of Starkey Halo hearing aids. These hearing aids are designed so that audio sent by Bluetooth can be blended with the normal output of the devices.

"In effect, I hear the Wi-Fi sound mixed into my normal hearing."

In the advent of voice activated systems such as Siri and Google Glass, he believes everyone will soon want to wear an earpiece connecting them to their smartphone.

He said: "We're reaching a new stage of how we interact with our devices. It's an excellent time to think about what tools we can build when we're in constant conversation with the machines around us."

On an individual level, he says the project has helped to change his attitude to hearing loss. "It was a big blow to learn I was going deaf at such a young age, but through this project I've seen that actually I can use the situation I'm in to my advantage, and explore abilities that nobody else gets to experience," said Mr Swain.

"I don't feel like I've lost something any more, instead I feel like I've gained something."

You can read more about Mr Swain's project in his essay for New Scientist.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments