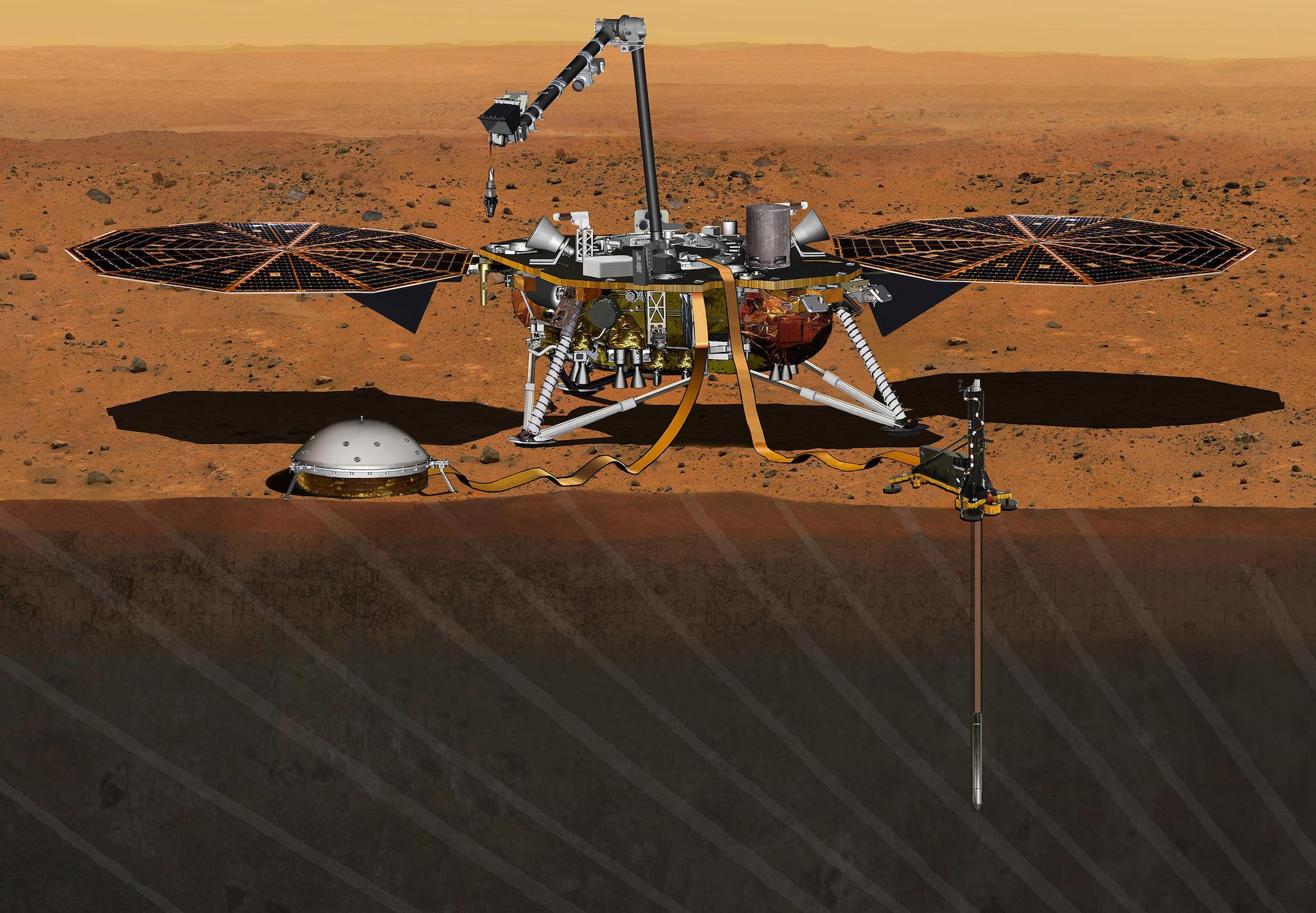

Nasa's Mars InSight mission to dig into red planet to answer its deepest mysteries

Getting onto the surface is incredibly difficult – let alone digging through and into it

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Nasa is about to launch a rover to dig deep into Mars.

The engineers behind the mission hope that it could find life and the answer to other mysteries about how the planet was formed.

The InSight mission will set off six years after Nasa last sent one of its robot travellers to investigate the red planet. And it will continue the same work, digging into the surface to try and learn more about what is hidden beneath.

It will take the first measurements of “marsquakes”, for instance, and will look into why the planet seems to wobble a little as it spins around. It is not looking for alien life, but the information it finds could be important to understanding whether the planet would be able to support it.

The lander’s instruments will allow scientists “to stare down deep into the planet”, said the mission’s chief scientist, Bruce Banerdt of Nasa’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory.

“Beauty’s not just skin deep here,” he said.

But Nasa hopes that the mission does not run into some of the same problems as other visitors to Mars: only 40 per cent of missions launched there have actually been a success. Engineers are, however, ready for exciting surprises, noting how little we know about Mars and how likely it is we could be surprised when we drill deep into its surface.

The $1bn (£7.5m) US-European mission is the first dedicated to studying the innards of Mars. By probing Mars’s insides, scientists hope to better understand how the red planet – any rocky planet, including our own – was formed 4.5 billion years ago.

Mars is smaller and geologically less active than its neighbour Earth, where plate tectonics and other processes have obscured our planet’s original makeup. As a result, Mars has retained the “fingerprints” of early evolution, said Mr Banerdt.

In another first for the mission, a pair of briefcase-size satellites will launch aboard InSight, break free after liftoff, then follow the spacecraft for six months all the way to Mars. They won’t stop at Mars, just fly past. The point is to test the two CubeSats as a potential communication link with InSight as it descends to the red planet on 26 November.

These Mars-bound cubes are nicknamed WALL-E and EVE after the animated movie characters. That’s because they’re equipped with the same type of propulsion used in fire extinguishers to expel foam. In the 2008 movie, WALL-E used a fire extinguisher to propel through space.

InSight is scheduled to rocket away from central California’s Vandenberg Air Force Base early Saturday. It will be Nasa’s first interplanetary mission launched from somewhere other than Florida’s Cape Canaveral. Californians along the coast down to Baja will have front-row seats for the pre-dawn flight.

No matter the launching point, getting to Mars is hard.

The success rate, counting orbiters and landers by Nasa and others, is only about 40 per cent. The US is the only country to have successfully landed and operated spacecraft on Mars. The 1976 Vikings were the first landing successes. The most recent was the 2012 Curiosity rover.

InSight will use the same type of straightforward parachute deployment and engine firings during descent as the Phoenix lander did in 2008. No bouncy air bags like the Spirit and Opportunity rovers in 2004. No sky crane drop like Curiosity.

Landing on Mars with a spacecraft that’s not much bigger than a couple of office desks is “a hugely difficult task, and every time we do it, we’re on pins and needles,” Mr Banerdt said.

It will take seven minutes for the spacecraft’s entry, descent and landing.

“Hopefully, we won’t get any surprises on our landing day. But you never know,” said Nasa project manager Tom Hoffman.

Once on the surface, InSight will take interplanetary excavation to a “whole new level”, according to Nasa’s science mission director, Thomas Zurbuchen.

A slender cylindrical probe, dubbed the “mole”, is designed to tunnel nearly 16ft (5m) into the Martian soil. A quake-measuring seismometer, meanwhile, will be removed from the lander by a mechanical arm and placed directly on the surface for better vibration monitoring. InSight is actually two years late flying because of problems with the French-supplied seismometer system that had to be fixed.

The 1,530lb (694kg) InSight builds on the design of the Phoenix lander and, before that, the Viking landers. They’re all stationary three-legged landers; no roaming around. InSight stands for “Interior Exploration using Seismic Investigations, Geodesy and Heat Transport”.

InSight’s science objectives, however, are reminiscent of Nasa’s Apollo programme.

Back in the late 1960s and early 1970s, the Apollo moonwalkers drilled up to 8ft (2.5m) into the lunar surface so scientists back home could measure the underground flow of lunar heat. The moon still holds seismometers left behind by the 12 moonmen.

Previous Mars missions have focused on surface or close-to-the-surface rocks and minerals. Phoenix, for instance, dug just several inches down for samples. The Martian atmosphere and magnetic field also have been examined in detail over the decades.

“But we have never probed sort of beneath the outermost skin of the planet,” said Mr Banerdt.

The landing site, Elysium Planitia, is a flat equatorial region with few big rocks that could damage the spacecraft on touchdown or block the mechanical mole’s drilling. Mr Banerdt jokingly called it “the biggest parking lot on Mars”.

Scientists are shooting for two years of work – that’s two years by Earth standards, or the equivalent of one full Martian year.

“Mars is still a pretty mysterious planet,” Mr Banerdt said. “Even with all the studying that we’ve done, it could throw us a curveball.”

Additional reporting by agencies

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments