The Independent's journalism is supported by our readers. When you purchase through links on our site, we may earn commission.

The Prometheoarchaeum microbe may hold the key to unlocking the human evolution

In the scientific hunt for the bridge between simple- and complex-celled life, says Carl Zimmer, the discovery of an odd microbe may reveal how life on earth took that all-important leap

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.A bizarre tentacled microbe discovered on the floor of the Pacific Ocean may help explain the origins of complex life on this planet and solve one of the deepest mysteries in biology, scientists reported last week.

Two billion years ago, simple cells gave rise to far more complex cells. Biologists have struggled for decades to learn how it happened.

Scientists have long known that there must have been predecessors along the evolutionary road. But to judge from the fossil record, complex cells simply appeared out of nowhere.

The new species, called Prometheoarchaeum, turns out to be just such a transitional form, helping to explain the origins of all animals, plants, fungi – and, of course, humans. The research was reported in the journal Nature.

“It’s actually quite cool – it’s going to have a big impact on science,” says Christa Schleper, a microbiologist at the University of Vienna who was not involved in the new study.

Our cells are stuffed with containers. They store DNA in a nucleus, for example, and generate fuel in compartments called mitochondria. They destroy old proteins inside tiny housekeeping machines called lysosomes.

Our cells also build themselves a skeleton of filaments, constructed out of Lego-like building blocks. By extending some filaments and breaking others apart, the cells can change their shape and even move over surfaces.

Species that share these complex cells are known as eukaryotes, and they all descend from a common ancestor that lived an estimated 2 billion years ago.

Before then, the world was home only to bacteria and a group of small, simple organisms called archaea. Bacteria and archaea have no nuclei, lysosomes, mitochondria or skeletons.

Evolutionary biologists have long puzzled over how eukaryotes could have evolved from such simple precursors.

In the late 1900s, researchers discovered that mitochondria were free-living bacteria at some point in the past. Somehow they were drawn inside another cell, providing new fuel for their host.

In 2015, Thijs Ettema, of Uppsala University in Sweden, and his colleagues discovered fragments of DNA in sediments retrieved from the Arctic Ocean. The fragments contained genes from a species of archaea that seemed to be closely related to eukaryotes.

Ettema and his colleagues named them Asgard archaea (Asgard is the home of the Norse gods). DNA from these mystery microbes turned up in a river in North Carolina, hot springs in New Zealand and other places around the world.

Asgard archaea rely on a number of genes that previously had been found only in eukaryotes. It was possible that these microbes were using these genes for the same purposes – or for something else.

“Until you have an organism, you cannot really be sure,” Schleper says.

Masaru K Nobu, a microbiologist at the National Institute of Advanced Industrial Science and Technology in Tsukuba, Japan, and his colleagues managed to grow these organisms in a lab. The effort took more than a decade.

The microbes, which are adapted to life in the cold sea floor, have a slow-motion existence. Prometheoarchaeum can take as long as 25 days to divide. By contrast, E coli divides once every 20 minutes.

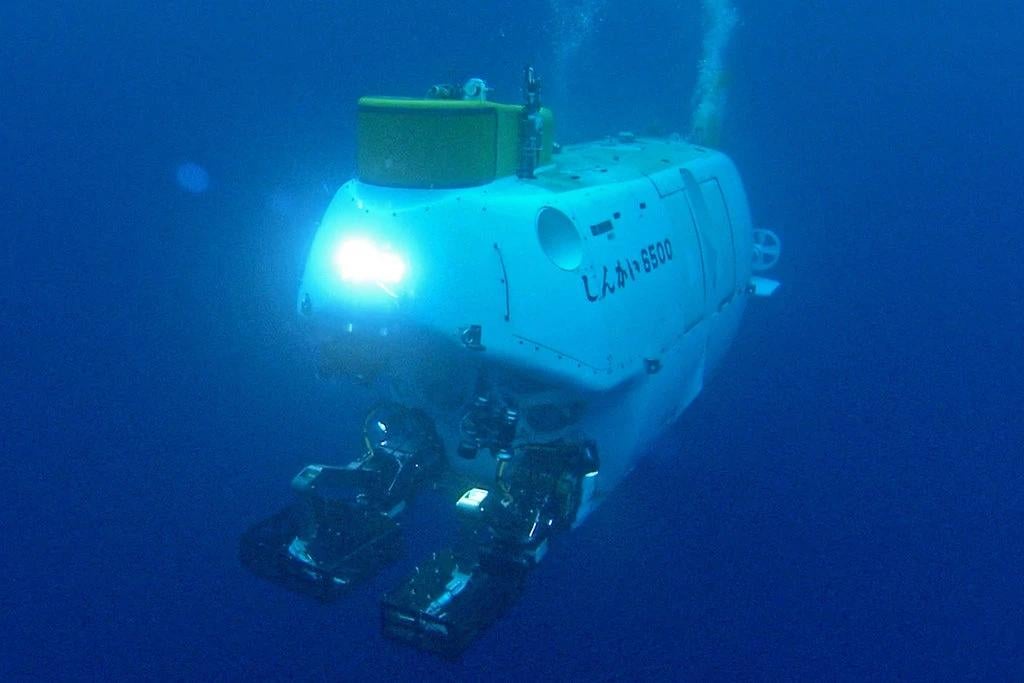

The project began in 2006, when researchers hauled up sediment from the floor of the Pacific Ocean. Initially, they hoped to isolate microbes that eat methane, which might be used to clean up sewage.

In the lab, the researchers mimicked the conditions in the sea floor by putting the sediment in a chamber without any oxygen. They pumped in methane and extracted deadly waste gases that might kill the resident microbes.

The mud contained many kinds of microbes. But by 2015, the researchers had isolated an intriguing new species of archaea. And when Ettema and colleagues announced the discovery of Asgard archaea DNA, the Japanese researchers were shocked. Their new, living microbe belonged to that group.

The researchers then undertook more painstaking research to understand the new species and link it to the evolution of eukaryotes.

The researchers named the microbe Prometheoarchaeum syntrophicum, in honor of Prometheus, the Greek god who gave humans fire – after fashioning them from clay.

“The 12 years of microbiology it took to get to the point where you can see it down a microscope is just amazing,” says James McInerney, an evolutionary biologist at the University of Nottingham who was not involved in the research.

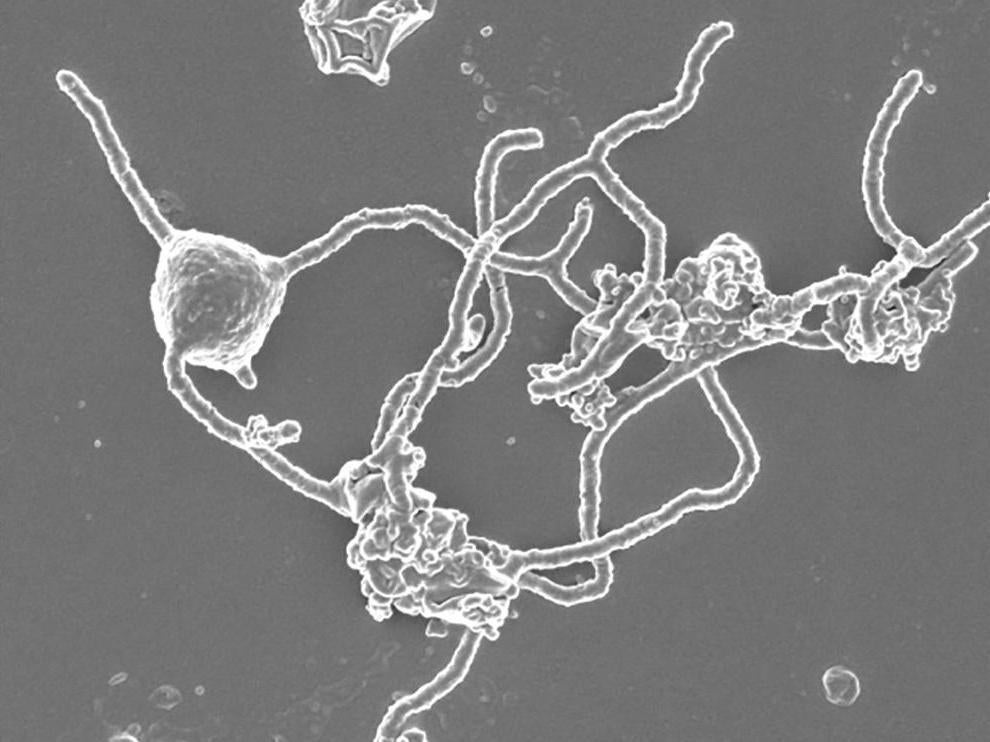

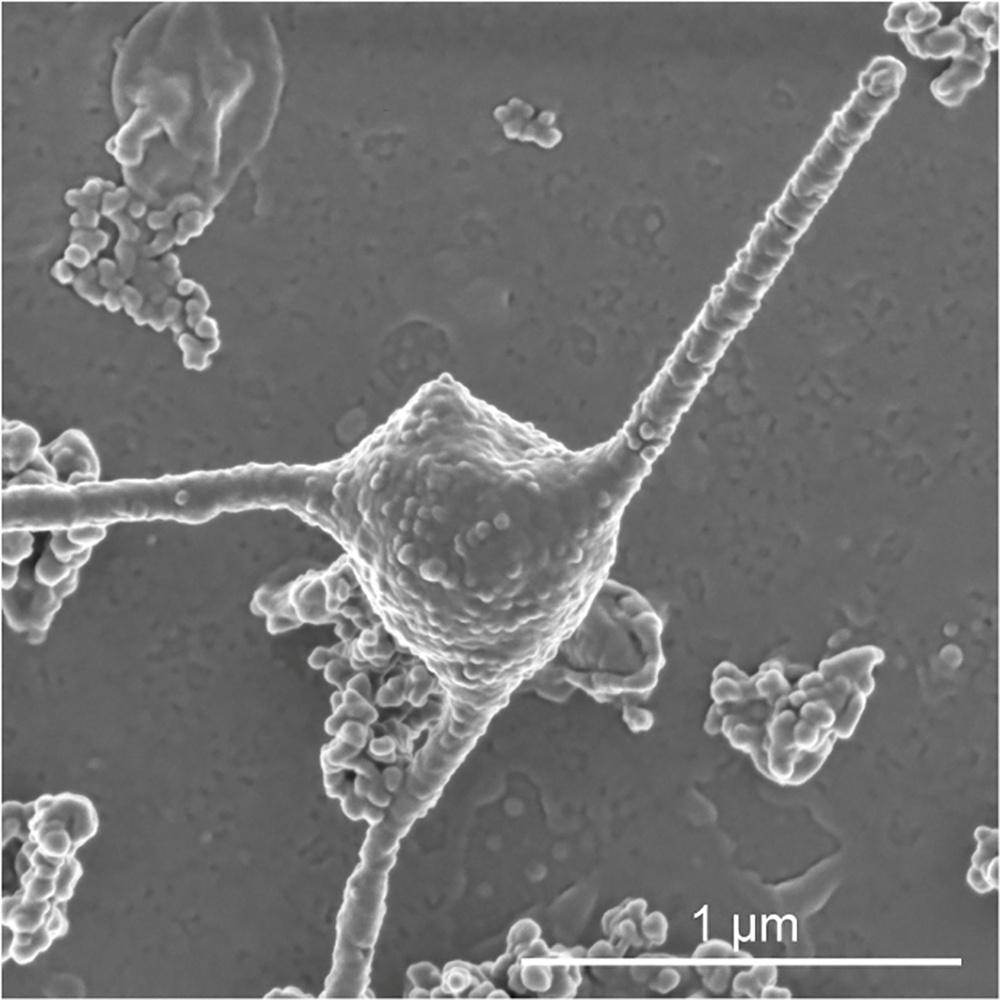

Under the microscope, Prometheoarchaeum proved to be a strange beast. The microbe starts out as a tiny sphere but, over the course of months, it sprouts long, branching tentacles and releases a flotilla of membrane-covered bubbles.

It proved even stranger when the researchers examined the cell’s interior. Schleper and other researchers had expected that Asgard archaea used their eukaryote-like proteins to build some eukaryote-like structures inside their cells. But that’s not what the Japanese team found.

“On the inside, there’s no structure, just DNA and proteins,” Nobu says.

This finding suggests that the proteins that eukaryotes used to build complex cells started out doing other things, and only later were assigned new jobs.

Nobu and his colleagues are now trying to figure out what those original jobs were. It’s possible, he says, that Prometheoarchaeum creates its tentacles with genes later used by eukaryotes to build cellular skeletons.

Schleper wanted to see more evidence for this idea. “There are very nice arms on other archaea,” she observes. But those other species aren’t using proteins so similar to ours.

Before the discovery of Prometheoarchaeum, some researchers suspected that the ancestors of eukaryotes lived as predators, swallowing up smaller microbes. They might have engulfed the first mitochondria this way.

But Prometheoarchaeum doesn’t fit that description. Nobu’s team often found the microbe stuck to the sides of bacteria or other archaea.

Instead of hunting prey, Prometheoarchaeum seems to make its living by slurping up fragments of proteins floating by. Its partners feed on its waste. They, in turn, provide Prometheoarchaeum with vitamins and other essential compounds.

Nobu speculated that a species of Asgard archaea on the sea floor dragged bacteria into a web of tentacles, drawing them into even more intimate association. Ultimately, it swallowed the bacteria, which evolved into the mitochondria fueling every complex cell.

McInerney is sceptical that Prometheoarchaeum could provide a clear picture of how our ancestors took in mitochondria 2 billion years ago. “This is an organism alive today in 2020,” he says.

As Nobu’s team continues to study Prometheoarchaeum, they’re also hunting for its relatives in their sea floor mud. Those microbes may turn out to be even closer to our own ancestry – and may offer even more unexpected clues.

“We hope this will help us understand ourselves better,” Nobu says.

© New York Times

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments