The UAE’s plan to terraform Mars could also transform its own desert nation

The space agency hopes to build a city in the Martian desert by the end of the next decade, writes Adam Smith

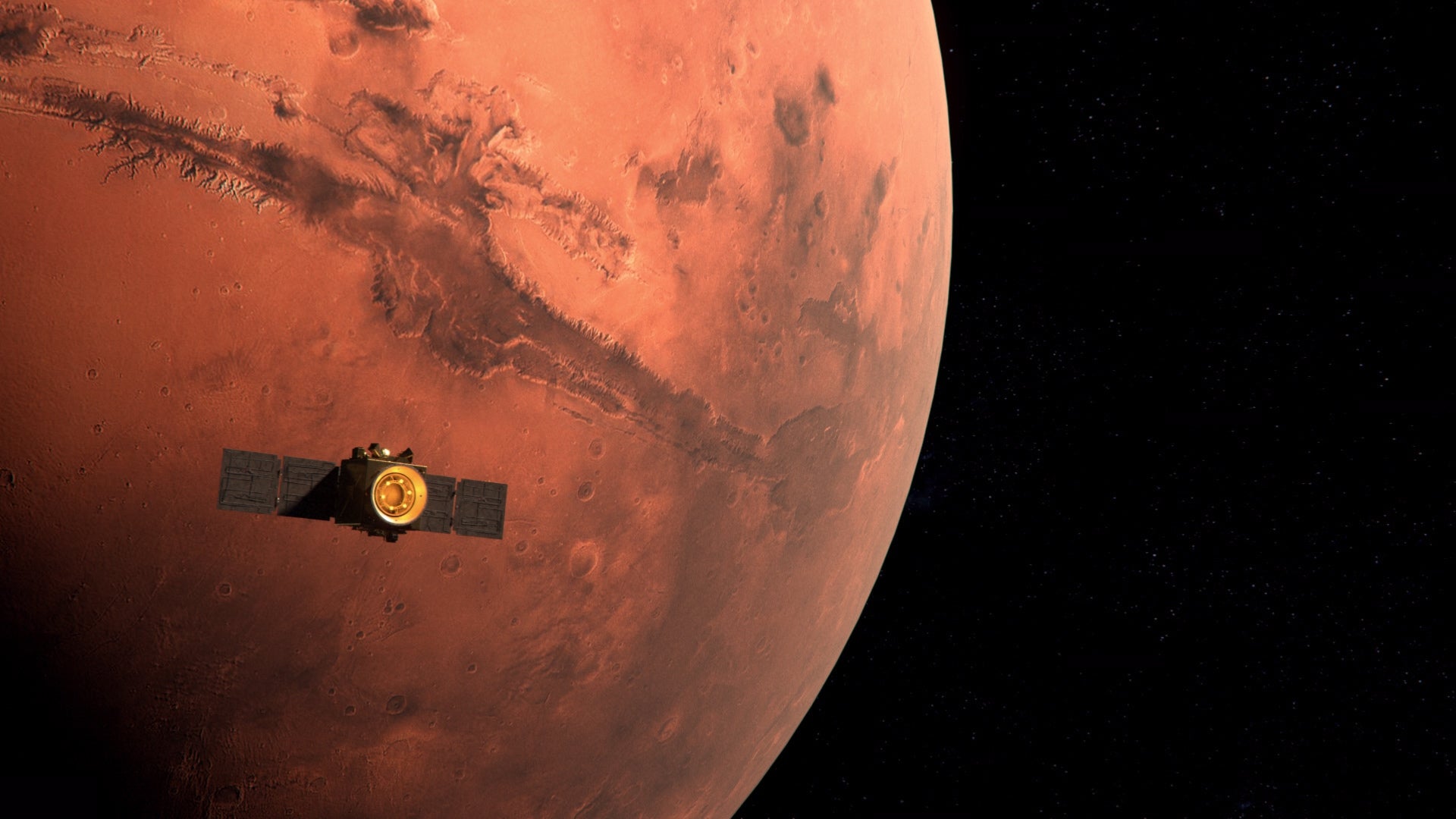

The astonishing launch of the Hope Probe, a car-sized spacecraft set for Mars, was a key moment in the history of Arab space flight.

Despite the United Arab Emirates Space Agency (UAESA) only being in existence for seven years, the success of the mission made the UAE the first Arab country and the fifth on Earth to reach the Red Planet, and only the second to ever reach Mars’ orbit on its first attempt.

The success of the mission has set the UAE towards loftier goals. In 2028, a new Emirati interplanetary mission will make a close approach to Venus before journeying to the asteroid belt located 448 million kilometres from our Sun.

These missions open new possibilities for humanity to explore the stars, but the benefits for the UAE specifically are twofold: the idealism of space exploration gives the UAE the perfect rhetoric to attract more business, while terraforming the Red Planet could lead to technological revelations that could transform the desert that the country is built upon.

UAESA is not like other space agencies. Nasa was established in 1953 to compete with Kosmicheskaya programma SSSR, the Soviet space program that would officially become Roscosmos in 1992. The two nations’ battle over the cosmos during the Cold War is well known, but in the heat of the desert cities like Dubai were still developing – only establishing its first telephone company and the first hotel in 1959.

In the 1960s, with the discovery of oil reserves, that would all change. The city’s population grew by 300 per cent by 1975, and eventually develop it into the metropolis known today. The age of black gold cannot last forever, though. Climate change, the result of years of dependency on fossil fuels, will force us to change the way we harvest energy or die.

The UAE, conscious of the writing on the wall, now wants to diversify its economy and sees the pioneers of a new, privately-owned, space age as a key opportunity. The elevated dreams of space exploration and the slick marketing of global capitalism turn out to slot together neatly.

However, to encourage businesses to invest in space the UAE needs a dream to sell: it found one in what it calls Mars 2117. This program, announced in 2017, claims humans will have liveable environments, and 60,000-strong colonies, on Mars within the century.

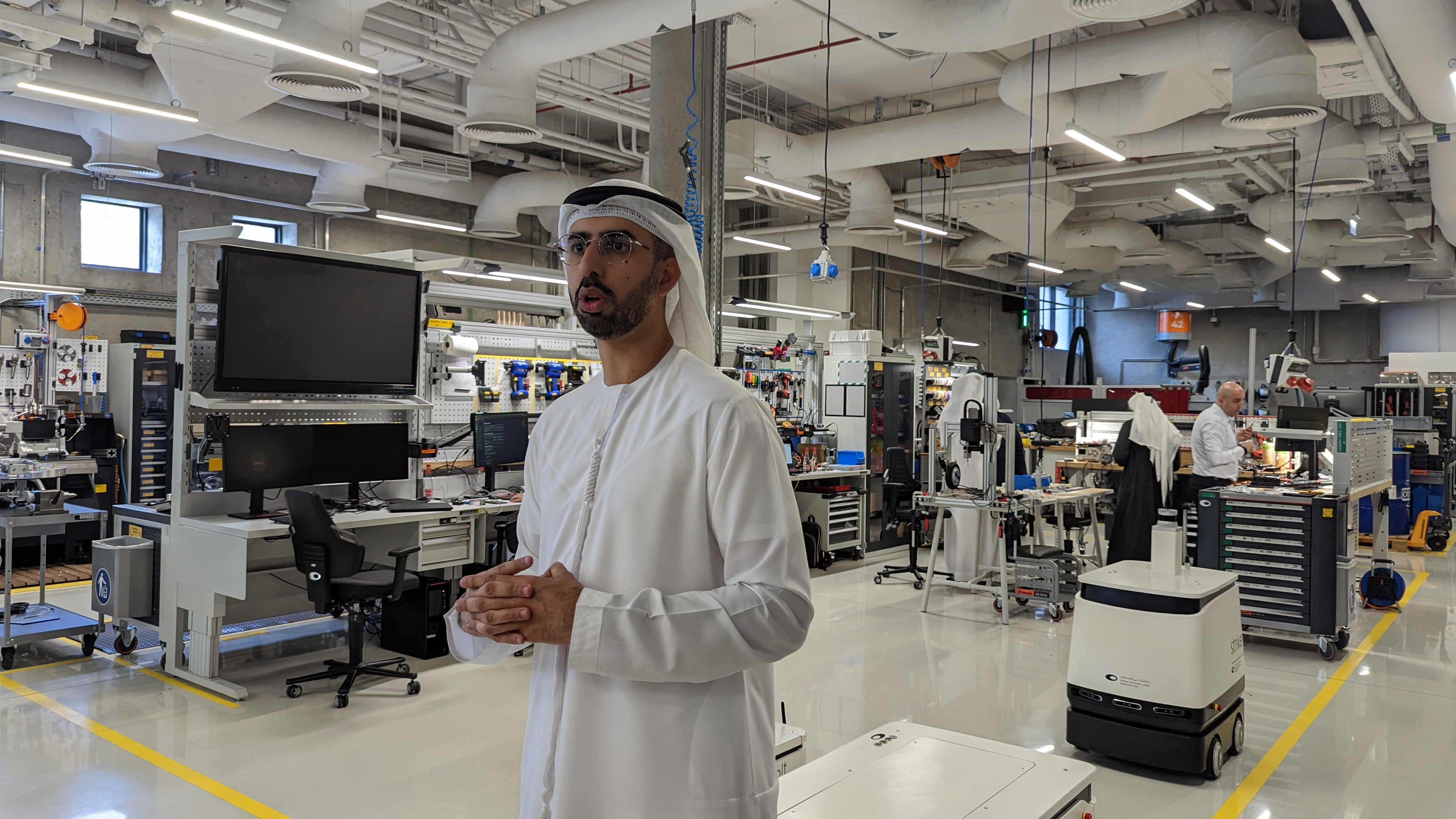

“If we are going to dream about Mars, let’s not have a mediocre dream, let’s dream big, and if we achieve 10 per cent of it, it’s going to be very impressive”, Omar Al Olama, the UAE minister for AI and remote working, told The Independent. “Many futurists, many studies prove that the coming economy is going to be a space economy and it’s a multi-trillion-dollar economy that will give us access to resources … we know that we will have to play in it at one point of time? Why not start now?”

The UAESA’s philosophy, similar to SpaceX and Blue Origin, might be summarised by Facebook founder Mark Zuckerberg’s infamous motto “move fast and break things”. When developing the Hope Probe, Sheikh Mohamed bin Zayed bin Sultan Al Nahyan gave specific requirements, Omran Sharaf, Emirates Mars mission project director recalls. It needed to reach Mars before December 2021, it needed to be built for $200 million, and it needed to be completed in six years.

In contrast, other nations generally build these missions over 10 to 12 years, with a larger budget, and with considerably more than zero experience in sending spacecrafts to Mars.

There was a last requirement, Mr Sharaf says he was told: that the job was “not to deliver a mission around Mars”. It was “to lead a disruptive change that I would like to see in multiple sectors that are critical and core to the future of the UAE … scientific and technical capabilities to address these [economic] challenges”.

In this light, it is easy to view the UAE’s interest in space as primarily an economic one. “The Mars 2117 strategy is more about addressing challenges we have on Earth, especially more specific to the UAE. We talk about water security, food security, energy security,” Mr Sharaf says. “If you have a human living there, in that harsh environment, there’s a lot of that technology you can actually use to serve your challenges here on Earth, especially on the desert.”

The timeline for these endeavours is less clear, however. “You can’t come up and say, ‘I’ll come up with this discovery [by this date], it’s very difficult”, Mr Sharaf said. “You can predict certain trends and build on them, but to be very specific that’s a very difficult thing to do”. The uncertainty is reminiscent of Elon Musk, who predicted a Mars landing as early as 2024, revised it to 2026, and now suggests 2029 as a potential date.

The UAE’s promotional website for the mission is more definite. It envisions that the city will be built by robots, that the first humans will land by 2037, the first settlement completed by 2039, and the first building constructed using only materials from Mars in 2064. Other experts remain sceptical. “This is really beyond my time horizon”, Jonathan McDowell, an astronomer at the Centre for Astrophysics, told The Independent when asked for his predictions on the project. “I think you need a science fiction writer.”

But success will not be measured not by how close humans come to the stars; instead, it will be by the businesses that come to Dubai for this new push into space, and the young Arabs that are inspired to build businesses of their own.

“With the Venus mission, and the asteroid belt, the success will be the startups. How much of those startups are able to work [and] gain capacity in the private sector”, Mr Sharaf says. “We want the future Elon Musk for the UAE, we want a future Bill Gates, we want a future [Warren] Buffett.”

This is not only an attitude taken by the UAE. In the United Kingdom, which has not independently launched a satellite since 1971, the space industry has increased by 300 per cent since 2010 and generates an estimated £15 billion every year. The global small satellite market alone is worth approximately £400 billion, and the UK is aiming to take 10 per cent of that market by the end of the decade.

For the Emirates, there is a sense that space is the next logical continuation for a country where the native people were merchants and manufacturers, where the next horizon to sail towards is in a ship that travels upwards. Would the country take the same approach if it did not have an environment so similar to Mars, but instead was wet and cold? “I think our approach would be different because the priorities will be different, and when the priorities are different, the budgets are different”, Mr Sharaf said.

Behind any idealism of an interstellar future for humanity, though, remains the practicalities of the work necessary to create it. In theory, every person and startup on Earth has access to a breathable atmosphere, accessible water, nourishing food, and a global economy ready to support them. In reality, nearly 2.37 billion humans do not have access to adequate food, 2.2 billion people do not have safely managed drinking water services, and more than 700 million people — 10 per cent of the global population – live in poverty.

In the UAE specifically, the multi-billion-dollar Expo 2020 – which the country announced to attract global tourists and investors – has been criticised widespread labour exploitation and racial discrimination, something the country has struggled with for years.

“The way they treat the staff is like slaves, I mean modern day slavery,” one unnamed Indian worker told London-based human rights group Equidem. The government has denied such allegations.

Building one grand carnival like Expo 2020 is absurdly miniscule compared to the challenge of terraforming a whole other planet. “The sales pitch for going to Mars is that it’s going to be cramped, dangerous, difficult, very hard work and you might die,” Mr Musk has said. “That’s the sales pitch. I hope you like it.” For too many, however, this is still the sales pitch for living on Earth – and people have pushed back against what they see as joy-rides for the super-rich while everyday people still struggle to afford the basics.

The counterargument is that a rising tide lifts all ships. “I read a very interesting article,” Mr Al Olama says, “that argues a middle class person anywhere on Earth today lives a better life than John D. Rockefeller lives in his prime … he would have died to have a watermelon in the winter.

“There are certain things you can enjoy today that to him was a dream. The future is always actually better off than the past. That divide is something that is a result of capitalism.”

Similarly, the first passenger airline was not started until 1914; now there are tens of millions of flights every year. Space travel, currently restricted to the rich and powerful, may also become more common in the same way if people wait long enough.

But they might be waiting a long time. Britain’s standard of living has had the worst fall since the 1950s, and the share of global wealth owned by billionaires’ has risen from one per cent to over three per cent since 1995. In the space industry, and a world with international collaboration, governments are still unable to solve global crisis like the space debris that risks keeping us trapped on the planet, and legislation for other plants could still fall into the same pitfalls of those on Earth. The thing about a rising tide is that you can only survive it if you have a ship – or a spaceship.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks