AI developing faster than laws aiming to regulate it, academic warns

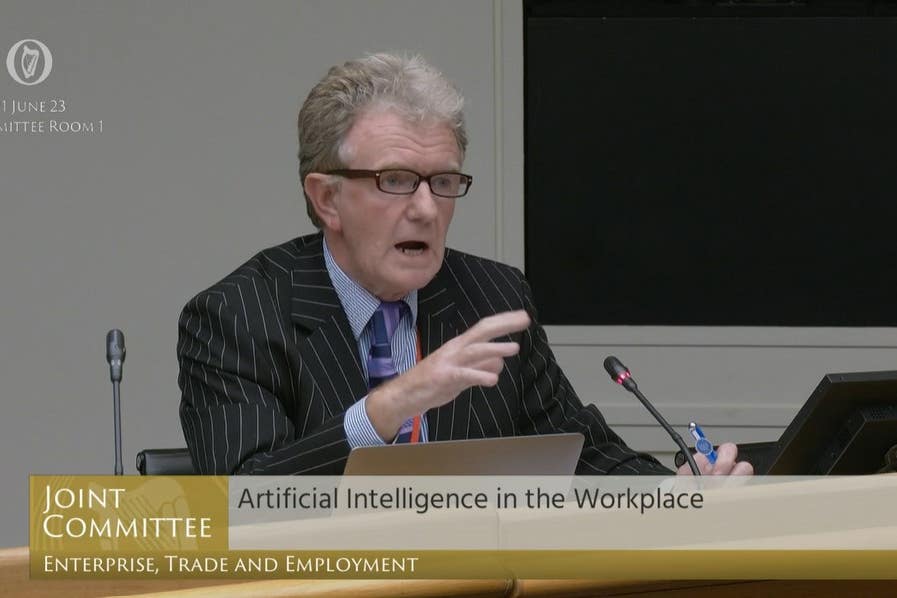

Professor Gregory O’Hare said AI offers ‘profound opportunities’, but could also be used for Machiavellian purposes.

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Artificial intelligence (AI) is developing at a faster pace than laws can be drafted in response, an academic has warned.

Although the technology has been around in some form for some time, the rate at which it is changing and improving is the new, key challenge, senators and TDs were told.

The Oireachtas Enterprise Committee heard that AI can offer “profound opportunities” to help people, but can also be used to reduce white-collar employees’ salaries and even prompt diplomatic incidents.

Professor of AI at Trinity College Dublin Gregory O’Hare cited cases including technology beating a world chess champion in 1997, as well as fake AI-generated images of Donald Trump being arrested and the Pope wearing a designer puffer jacket, as he outlined landmark moments in the development of the “disruptive technology”.

He said there have been many previous “false dawns and unrealised promises” about the technology’s potential, and that ChatGPT has gathered 100 million users in two months and is the fastest-growing technology in history.

He said white-collar professions like the law, academia, marketing, architecture, engineering, journalism and the creative industries will all be “profoundly affected”, and cited a recent study which estimated that two-thirds of all US occupations will be affected by AI.

“In terms of the point around wages, I think there is certainly an opportunity for employers to reduce salaries,” he said.

The Irish Congress of Trade Unions (ICTU) argued that unions should be involved at an early stage in any initiatives looking to address concerns around AI.

Dr Laura Bambrick, of the ICTU, said the EU AI Act is not suitable to regulate AI and is “more than disappointing” from workers’ point of view, stating that the amendments tabled offer some comfort but “don’t go far enough”.

“It only requires software providers to self-assess their own technology between low- and high-risk before putting it on the market, and did not include any rules on the use of AI in the workplace,” she said.

The velocity of AI technology is, alas, fast exceeding the rate at which the law around AI can be framed

Prof O’Hare said he believes the current legislative framework proposed to regulate AI is not “in a position to be able to respond with the speed that we need”.

He added: “The velocity of AI technology is, alas, fast exceeding the rate at which the law around AI can be framed.”

Cork East TD David Stanton said that statement is “quite scary”, and “science fiction is actually becoming science fact”.

He suggested the topic is so serious and developing at such a pace that it could warrant setting up a dedicated Oireachtas committee to discuss it.

During the session, committee chairman Maurice Quinlivan said he used ChatGPT to double-check that the three guests had not used ChatGPT to write their opening statements, with one TD remarking he was “using AI to check for AI”.

Prof O’Hare said it is difficult to assess how AI comes to a particular conclusion, even for experts.

“Not only is there typically not a set of algorithmic steps that one, even with a trained eye, could scrutinise, AI, and in particular deep AI, does not have an algorithmic basis.

“So, even were it to be the case that someone like myself, a professor of artificial intelligence, were I to look at a particular AI application that was using deep learning, I would have great difficulty in being able to establish, on the surface, how it actually arrived at its deduction and its recommendation or conclusion.”

It knows no political boundaries, it knows no geographic boundaries, no socio-economic boundaries. This is something that demands potentially a global position

He added that, while it is crucial to engage with all stakeholders involved, it will take “some considerable time”, and the rate at which AI is developing “does not afford us that level of time”.

Responding to the suggestion that the use of AI should be slowed down or halted to allow for consultation, he said: “We’re talking about something that knows no boundaries.”

“It knows no political boundaries, it knows no geographic boundaries, no socio-economic boundaries. This is something that demands potentially a global position. So Ireland needs to find a way and a voice into that global discussion.”

Ronan Lupton SC, of the Bar Council of Ireland, said that although AI has been around for some time, “where we’re moving to now, at the moment, is a sphere in an environment of extreme pace”, which is the “key challenge”.

He said AI could help people with speech disabilities to communicate, but also warned of the dangers of misinformation.

He said that newsrooms, instead of sending a draft article to a solicitor to check for defamation or other legal issues, are now using artificial intelligence technologies instead, which he said is “an interesting development”.

Prof O’Hare agreed with the potential of AI to help people with disabilities and said it is “very important that we do not throw the baby out with the bathwater”.

“This technology has profound opportunities, absolutely profound opportunities.”

But he suggested that, because the technology has been put out “into the wild”, it could be used for “sinister” means which could have financial or political implications, such as boundary incursions – and even wars.

“The question is will it always be used for good purpose, or is there a significant chance that it will be used for Machiavellian purposes?” he said.