Let the Dreamachine free your mind

In the Sixties, they believed it could enhance your creativity. Now it's back, and Matthew Bell tunes in, turns on, and... manages not to fall asleep

A werewolf with blood-red eyes is roaring towards me. Dandelions are doing cartwheels by the sea. No, I'm not trying to write poetry, I'm just having a very odd dream. Except that it's three o'clock in the afternoon and I'm not even asleep. Ooh, tessellating Moroccan tiles are flashing past my eyes! I am experiencing the Dreamachine, a 1950s invention designed to free the mind, and I think I'm going to be sick.

"Invention" is possibly a bit generous: Heath Robinson wouldn't think much of what is, after all, just a giant cheese grater on a turntable. On the box, it says "Metal Table Lamp, Made in China". Get it out and it does look like the sort of tat you trip over at Habitat: a knee-high stainless-steel cylinder with holes punched into the side. But plug it in, twiddle a nob, and the outer cylinder starts spinning round fast, throwing shapes all over the walls. Then you just close your eyes and let your imagination do the rest.

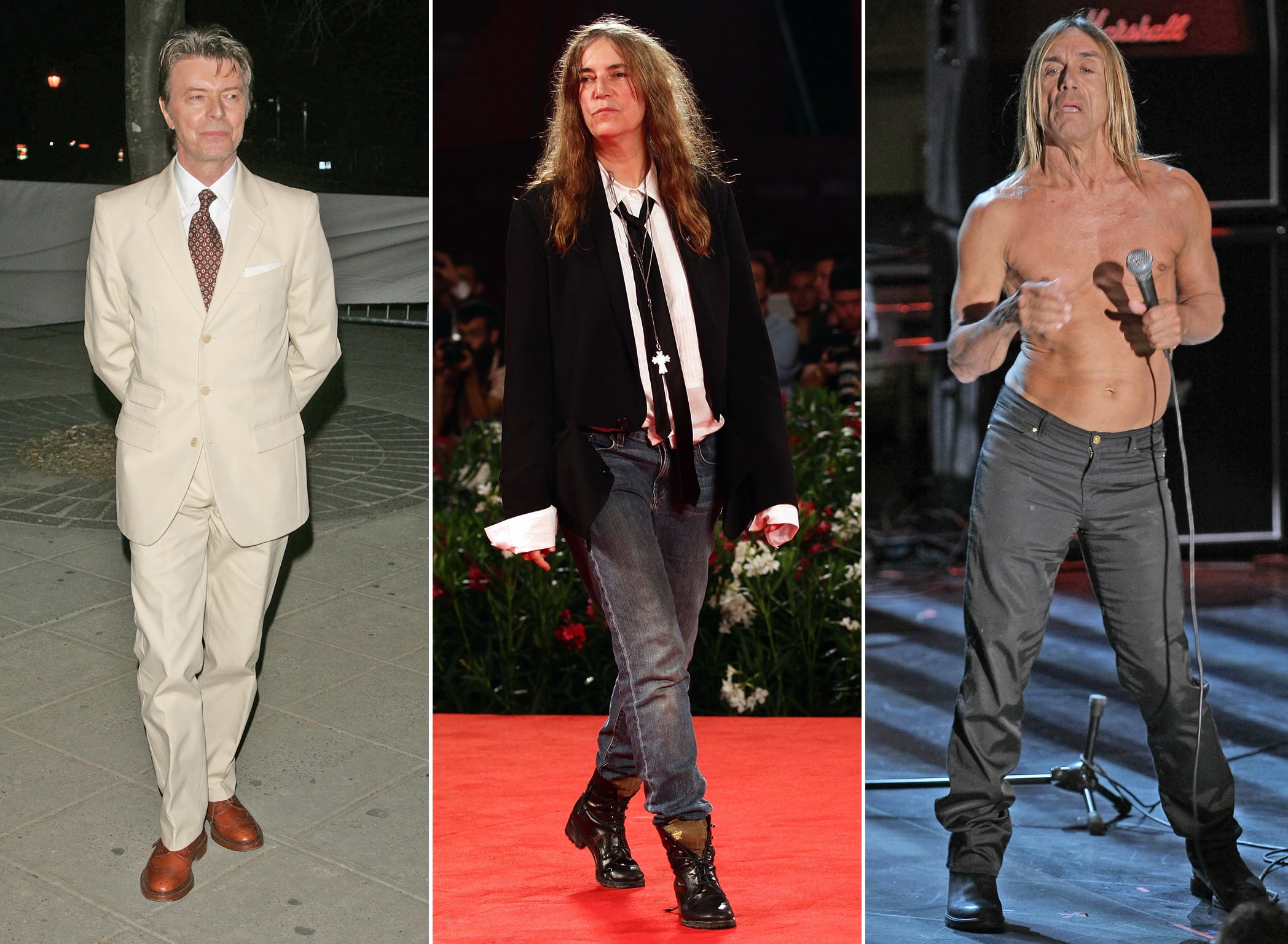

This was once a toy for Beat poets. Patti Smith used one, Kurt Cobain is said to have had a 72-hour bender with one, and David Bowie and Iggy Pop tried it too. Now, Canadian artist Johnny Smoke, 36, has resuscitated the design and, thanks to backing from John Weitner, a venture capitalist, has ordered 650 Dreamachines to be knocked up in a factory in China. As of this weekend, anyone with a spare £250 can buy one from Hackney's Apiary Studios.

The original "Dreamachine" was created by Brion Gysin, the experimental painter and poet. His great friend William S Burroughs, author of Naked Lunch, called him "the only man I ever respected". Gysin got the idea in 1958, after experiencing a "natural high" by chance. Travelling on an evening bus from Paris to Marseille, he closed his eyes as the vehicle entered an avenue of trees, and the flickering light "swept him out of time", he told Burroughs, into "a transcendental storm of colour visions".

He wanted a way to replicate this high, so with Ian Sommerville, a Cambridge maths graduate, he set about creating a stroboscope. This was no hippyish flimflam: the idea was to send out flashes that would be in tune with the brain's alpha waves. So the rotation speed and number of holes in the cylinder is very specific: 78 revolutions per minute, sending out 8 to 13 flashes per second.

But is it safe? Stroboscopic light can do funny things to your mind, and the effect has been likened to taking LSD. One in 4,000 people could suffer an epilectic fit. On the Thomas Beecham principle of trying anything once, except incest and folk dancing, I carried out a semi-controlled scientific experiment. Well, I got into my finest Budd pyjamas and got ready for beddy-bye. Then I cleared the flotsam from my mind, sat cross-legged in front of the machine, and flicked it on. Gysin liked to say it was the first art object to be viewed with your eyes closed. I'm glad you're not supposed to keep them open, as even with them shut you feel dizzy pretty quickly. The blood in your eyelids makes everything look red and black, and the speed of the flickering is like watching a wall of dead tellies. But relax into it, and soon figures start to emerge: kaleidoscopes of repeating shapes explode and morph into each other, like in the opening sequence of a Bond film. Tangerine trees and marmalade skies – oh look, there's the girl with kaleidoscope eyes. Inexplicably, I got a lot of Nordic animals: elk, reindeer, that kind of thing. I also started to get a headache. My parents might be reading, so I won't say it reminded me of an acid trip.

Apparently, it helps you to write better, though I haven't noticed. According to the novelist Margaret Atwood, who owns a Dreamachine, it can be helpful if you have writer's block, or a problem to be solved. "Unless, of course, you simply nod off, which can also be refreshing."

Truth is, I think I would have preferred a nap. You're supposed to give it an hour, but 10 minutes was quite enough. There are only so many werewolves I want to see popping up out of my imagination. The beauty of this high, unlike most others, is that it's perfectly legal and you can end it at the flick of a switch. Did it free up my imagination? Not really. Do I feel a little bit sick? Yes. Would it make a good Christmas present for a hippy aunt? Definitely. But if this is what the Sixties was like, thank Shiva I wasn't there.

The dream that died

The hallucinatory effects of flashing lights on the brain have been studied since the 19th century, but the first "Dreamachine" was created by artist Brion Gysin and scientist Ian Sommerville in 1961. Sommerville came up with the idea of mounting the apparatus on a 78rpm record player. Both men were influenced by reading The Living Brain, by William Grey Walter.

During the 1950s, Gysin had been in Tangier, Morocco, where he opened a restaurant called the 1001 Nights. When he lost the business in 1958, he moved to Paris and moved into a cheap boarding house which became known as the Beat Hotel, where the poets hung out.

While living at the Beat Hotel, Gysin constructed his own model of a Dreamachine, which he continuously refined for production. He took out a patent and pitched it to various businesses, but no manufacturer would take it on. Gysin did succeed in exhibiting it at the Musée des Arts Décoratifs. And he also persuaded eminent arts patrons such as Peggy Guggenheim and Helena Rubinstein to display it in their galleries in Paris and Venice, though no sales resulted.

Gysin later remarked that when he told electronics manufacturers that the Dreamachine actually made people "more awake", they lost interest. "They were only interested in machines and drugs that made people go to sleep."

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments