If we teach animals how to ‘talk’ we have a duty to listen

To find a way to communicate effectively with other species might be a noble aim, but it raises huge ethical problems. Christine Manby explains

On 4 July 1971, Hanabiko the gorilla – known as Koko – was born at San Francisco Zoo. Any gorilla born in captivity could reasonably expect a degree of public attention but Koko captured the imagination of millions as she grew to be one of the most prolific non-human users of American Sign Language thus seeming to offer a chance to “talk to the animals” in real Dr Doolittle-style.

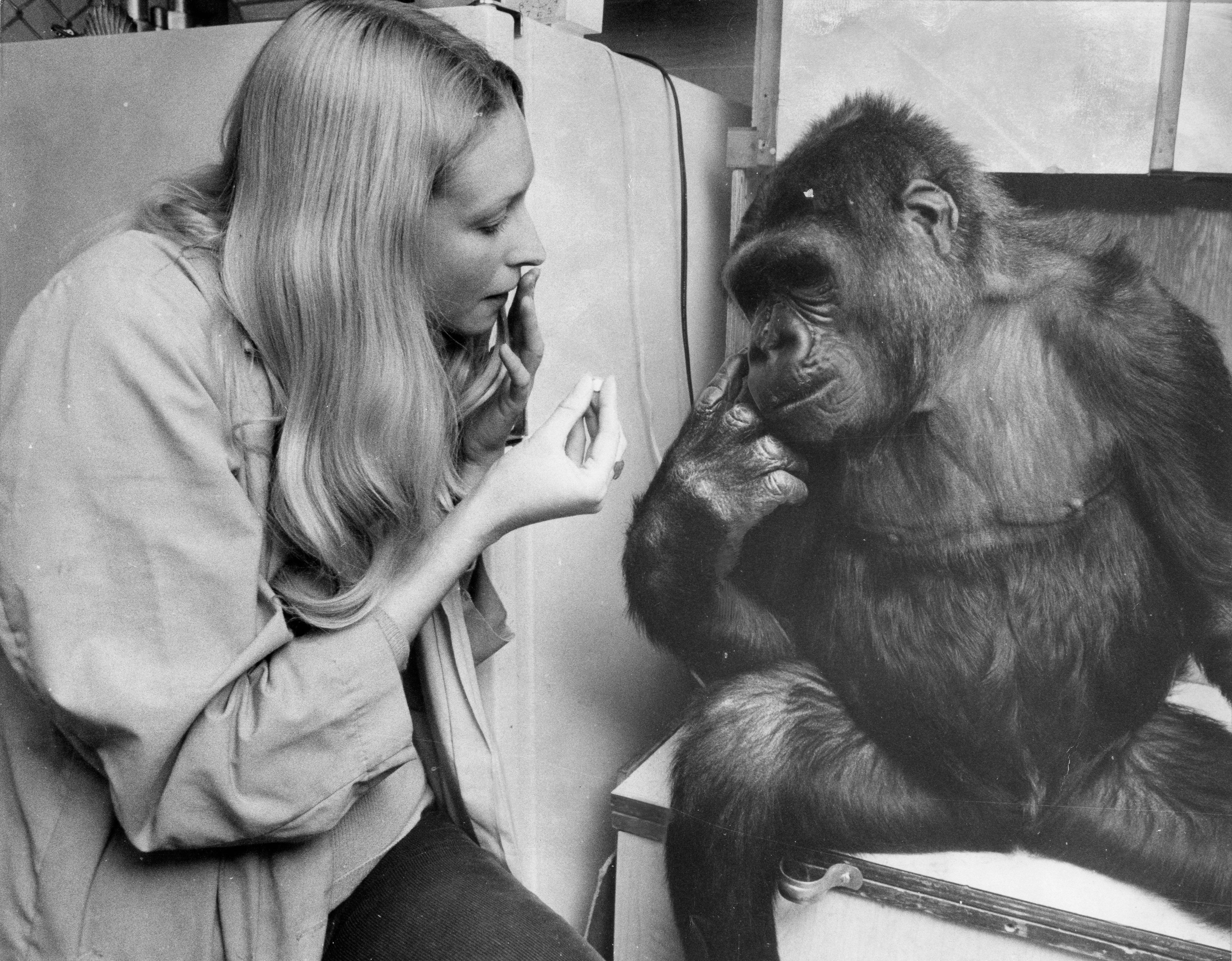

Koko’s first words were “food”, “drink” and “more” but animal psychologist Francine “Penny” Patterson, Koko’s keeper and sign language instructor, estimated that Koko came to have a vocabulary of more than a 1,000 signs. Having been exposed to spoken English since infancy, Koko could also understand more than twice as many spoken words.

During Koko’s life, which saw her move from the San Francisco Zoo via Stanford to the Gorilla Foundation, which Patterson set up in Koko’s honour, the gorilla was feted by the media, the scientific community and celebrities alike. She met Leonardo DiCaprio, William Shatner, Sting and The Golden Girls star Betty White. Koko was a big fan of American children’s television presenter Mister Rogers, having watched his show since she was an infant. She was thrilled to appear in an episode of Rogers’ Neighbourhood, where she taught the veteran entertainer to sign “I love you”. Eminent primatologists Diane Fossey and Jane Goodall visited Koko to ask her about her life in captivity. Flea from the Red Hot Chili Peppers taught Koko how to play bass guitar. For a while Koko even had her own pet cat, whom she named “All Ball”, demonstrating an unexpected ability to rhyme.

Koko could correctly use nouns, verbs and adjectives. She grasped abstract concepts. She could ask questions. She could also tell a lie, as she did when she tore a steel sink from a wall, then pointed at her cat and signed “she did it”.

Koko was able to express her feelings with eloquence too. In 2001, she met the actor Robin Williams. He visited Koko shortly after the loss of her gorilla companion, Michael. Patterson claimed that Williams made Koko laugh for the first time in six months. Many years later, when Koko heard about William’s death by suicide, she grew morose and signed, “woman cry”.

When she died in her sleep at the age of 46, Koko was mourned the world over as, in the words of the Gorilla Foundation, “an icon for interspecies communication and empathy”.

However, Koko was far from the only great ape to have learned to communicate via sign language. Research into the ability of apes to acquire human language began in the 1950s and reached its zenith in the Sixties and Seventies, when chimpanzees such as Washoe and Nim Chimpsky hit the headlines.

Washoe was born in West Africa in 1965. Captured by the US Air Force to be used in the US Space Programme, she was instead taken to the University of Nevada, where psychologists Allen and Beatrix Gardner began the process of teaching her to sign by raising her as a child in a trailer equipped with everything a human child might want or need.

Washoe came to know around 350 signs, which she was able to combine in simple sentences. When Washoe was homed with a younger male chimp, Loulis, whom she treated as a son, Loulis also came to sign by watching Washoe’s example.

Like Koko, Washoe was able to use signs to express more than her desire for a snack. Roger Fouts, who took over Washoe’s care when the Gardners left the training project, described a situation in which Washoe snubbed one of her caretakers, a woman named Kat, who had been off work while recovering from a miscarriage. If Washoe felt neglected, she would often send the guilty party to Coventry. To break the impasse, Kat signed “My baby died”. Washoe responded by looking into Kat’s eyes and making the sign for “cry”, in what Kat took to be a clear gesture of empathy.

How do you reconcile a tiny chimp in blue blankets, drinking from a bottle and wearing Pampers… And then, when he is 10 — stick him in a lab, in a cage, with nothing soft, nothing warm, with no people?

Roger Fouts was convinced that the complexity of Washoe’s communications showed such a high degree of emotional sensitivity that chimpanzees should have the same legal protections as human beings. In 1994 the Great Ape Project (GAP) was founded to this end, with the aim of achieving “the basic rights to life, freedom and non-torture of the nonhuman great apes”. GAP continues to fight for these rights all over the world.

Nim Chimpsky, Washoe’s contemporary in a Columbia University study led by Herbert S Terrace, was born in captivity. Nim was named as a jokey nod to Noam Chomsky, the MIT linguist who espoused the theory that real language is uniquely human. With Project Nim, Terrace hoped to prove otherwise. From the age of two weeks, Nim lived in a Manhattan brownstone with Columbia psychology student Stephanie LaFarge and her family. Nim was raised alongside LaFarge’s human children, and treated as a human child himself, even to the extent of wearing clothes.

LaFarge began the process of teaching Nim American Sign Language and by two years old, Nim had learned more than 150 signs. However, he had also become increasingly unmanageable. Nim was eventually removed from the LaFarge family home and returned to a compound at Columbia University, where his sign language training was continued by an ever-changing roster of caregivers.

Four years after Project Nim began, Herbert S Terrace assessed the chimp’s progress. Watching videos of Nim signing with his teachers, Terrace began to wonder if Nim’s “conversation” was really just imitation. Nim didn’t initiate signing and only rarely made a sign that hadn’t recently been modelled to him by a trainer.

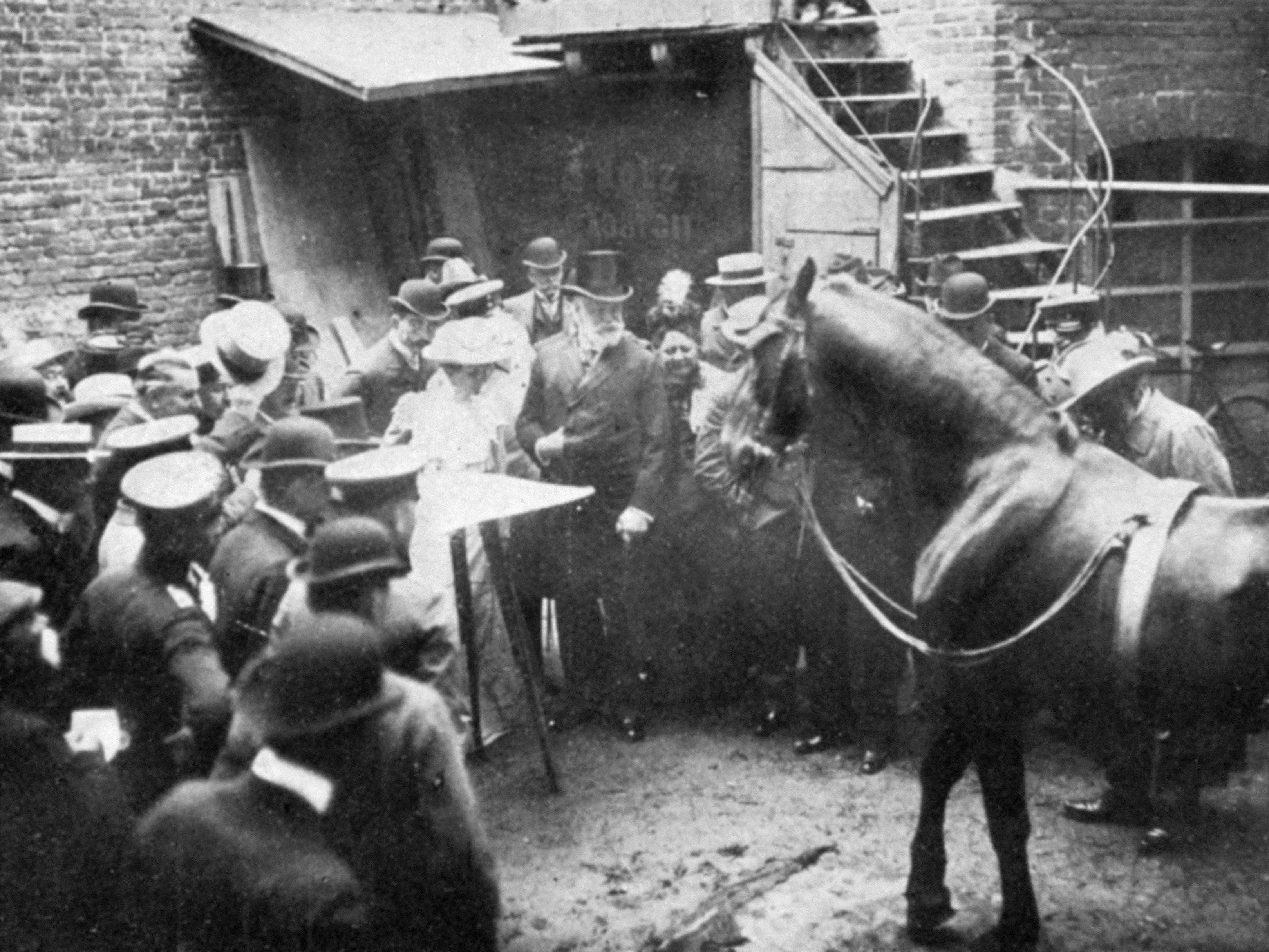

Terrace decided that what Nim’s hopeful trainers had considered to be evidence of the chimpanzee’s understanding of human language was just another manifestation of the “Clever Hans” effect. Clever Hans was a horse, who became a celebrity for appearing to be able to do simple sums by tapping out the answer with his hoof. Close study of Hans had shown that he wasn’t able to add numbers at all but was in fact responding to his owner’s body language. He stopped counting when something in his owner’s demeanour indicated that he’d reached the correct answer.

Regarding Nim, Terrace ultimately concluded that Chomsky was right. Nim was not using sign language to communicate ideas but merely repeating signs at random in the hope of getting a reward. Terrace subsequently ended the language project and Nim was sold to the Laboratory for Experimental Medicine and Surgery in Primates. In his short lifetime, Nim had gone from being treated as the cherished youngest child of a New York family to sharing a cage with other chimpanzees earmarked for hepatitis vaccine studies.

Fortunately, Nim’s celebrity meant that his plight came to the attention of the Fund For Animals, which rehomed him at its ranch. There Nim lived largely in isolation, confined to a pen due to his unpredictable displays of aggression. His carers reported that Nim continued to sign, when visited by anyone who could sign back at him, until his death at age 26 of a heart attack.

Reflecting on the experience of raising Nim as a human child, his surrogate mother Stephanie LaFarge came to believe that Project Nim was ultimately unethical, tricking the chimpanzee “into thinking he is a human being with no plan for protecting him”.

LaFarge’s daughter, Jennie Lee, who was 13 when Nim joined the family, went further. She told Elizabeth Hess, who interviewed her and her mother for Nim Chimpsky: The Chimp Who Would Be Human: “How do you reconcile a tiny chimp in blue blankets, drinking from a bottle and wearing Pampers… And then, when he is 10 – stick him in a lab, in a cage, with nothing soft, nothing warm, with no people? This is my brother. This is somebody that I raised – and that the system could let this happen was shocking.”

The sad life of Nim Chimpsky highlights the huge ethical problems of teaching animals in captivity human language. Since those days when psychologists such as Terrace thought it was acceptable to raise an ape as a human before returning it to life in a lab, the focus has shifted to studying the ways animals communicate in their natural habitats and in their own way. However, attempts to teach animals to “speak human” are still ongoing and perhaps it’s unsurprising that one of the biggest language acquisition studies currently in progress began with an Instagram account.

Californian speech therapist Christina Hunger became a social media sensation when she documented her attempts to teach her dog Stella, a Catahoula / Australian Cattle Dog mix, to “talk” using adaptive technology. Armed with a series of plastic buttons, that could be loaded with a pre-recorded word, Hunger set about teaching Stella to talk using the same language facilitation strategies she uses with human children.

Hunger began with just one button, on to which was recorded the word “outside” – a very useful word when house-training a puppy. Hunger pressed the button every time she opened the door and it wasn’t long before Stella was pressing the button to let Hunger know when she wanted to be allowed out.

It’s easy to see how a pet owner might over-interpret a pet’s utterances but to what extent might they also be failing to recognise when their pet is saying something really important?

Since Hunger first introduced Stella to the buttons that allowed her to say “outside”, “play” and “water”, the buttons on Stella’s communication board have grown to number 48. Furthermore, Stella can combine as many as five words at a time into sentences. On Hunger’s website, she writes that Stella is able to “ask and answer questions, express her thoughts and feelings, make observations, participate in short conversations, and connect (with us) every single day”.

Hunger’s Instagram account charting Stella’s progress – @Hunger4Words – currently has 800k followers and her book, How Stella Learned to Talk: The Groundbreaking Story of the World’s First Talking Dog, was an instant New York Times bestseller. Hunger’s method has since been adopted by hundreds of dog owners keen to know what their own dogs are thinking. Some of those dogs have become stars in their own right, such as Bunny, a “sheepadoodle / existentialist”, who has more than 6 million followers on Tik Tok and, according to her owner Alexis Devine, a vocabulary of 92 words.

Bunny caught the attention of Leo Trottier, developer of CleverPet, an interactive feeding console for dogs. Having followed Bunny’s progress on her speaking buttons, Trottier developed FluentPet, a recordable button system similar to that used by Hunger. Trottier also connected Bunny and Devine to Federico Rossano at the Comparative Cognition Lab at UC San Diego.

Inspired by Bunny’s adventures in human language, Rossano and his colleagues set up a research project to find out whether this new generation of animals might finally prove Chomsky wrong. The project was named “They Can Talk”.

As of this summer, They Can Talk has almost 3,000 subjects, including several cats and horses. It differs in one very important way from the great ape experiments. Unlike Washoe, Nim and Koko, Rossano’s subjects have not been removed from their natural habitats to take part. Dogs in particular have a long history of living alongside human beings. This co-evolution has given dogs an unusually deep understanding of humans and they have already adapted their behaviour to better communicate with and even manipulate their human hosts – think “puppy eyes”. Modern dogs display behaviours such as gesturing with their eyebrows, which are not seen in their closest relatives, the wolf.

Rossano’s team will have their work cut out, watching their many subjects on video and trying to ascertain whether the animals are really using language in a human sense or reacting, just like Clever Hans. As the project’s website explains, “non-human animals' abilities to recognise small changes in the physical state of a human ‘conversation partner’ can be a major confound in studies of non-human animal cognition”.

Equally, “on the other side of this interaction are the possible confounds that we humans can bring. Non-human animals respond to the behavioural signals of our expectations, and then to this we add our own considerable capacity for interpretation… using our decades of experience with words to transform a dog pressing the 'love you' button into an expression of human-like affection. When we combine eager-to-please dogs with our own meaning-making minds, it's easy to be fooled into concluding that something language-like is happening even when it might not be.”

It’s easy to see how a pet owner might over-interpret a pet’s utterances but to what extent might they also be failing to recognise when their pet is saying something really important?

In one of the early videos on the Hunger4word’s Instagram account, Stella the dog has heard a noise outside and is trying to persuade her owner Christina Hunger to investigate. Between barking and whining, Stella presses the button for “look” nine times in quick succession, before clarifying her request by pressing “come outside”. It’s clear Stella is excited; possibly anxious.

Hunger writes in the caption that accompanies the video: “I’m impressed that Stella is communicating with language during her more heightened states, not just when she’s calm and in a quiet space. This shows me that words are becoming more automatic for her to use. It’s similar to when a toddler starts using language to express himself during times of frustration instead of only crying.”

But while Hunger marvels at Stella’s skill on the buttons, Stella’s frustration that her mistress isn’t responding to her request – “come outside and look” – is clear. The video ends before we get to find out what it was that had made Stella so agitated. To anyone who has ever known a dog, Stella’s body language showed she wasn’t mucking around. She wasn’t pressing the “look” button for the hell of it or in hope of a tummy rub. She was in earnest.

When we talk about an animal’s facility with human language, whether it be expressed via signing or pressing buttons, we often say things like, “Lassie has the language ability of the three-year-old child”.

Perhaps therein lies the problem. We assume that the “language ability of a three-year-old child” reflects the cognitive ability of that three-year-old human. Perhaps it would be more accurate to say that an animal being taught to “speak” using a method that is utterly alien to their natural way of going through life, has the “ability to press buttons like a three-year-old human”.

Koko was clear about the main message: man is harming the earth and its many animal and plant species and needs to ‘hurry’ and fix the problem

When an adult dog tells you to “look outside”, the words have a very different meaning to when a three-year-old child tries to attract your attention with the same words. Imagine meeting a tourist who doesn’t speak your language. If they came to you and said, “look outside” while expressing their agitation in every other way they knew how, would you dismiss their urgency on the grounds that they didn’t have the vocabulary to say “Lassie asked me to tell you she’s stuck down the well”?

An adult dog has an adult dog’s ability to detect a sound that a human ear won’t even pick up. Likewise it has a sense of smell several thousand times better than a human’s. There’s also evidence to suggest that dogs are better at reading human body language than we are. All this points to a dog’s ability to hear, smell and sense potential dangers in ways we humans can’t.

There is no doubt that to find a way to communicate quickly with other species (and maybe at some point with non-human creatures from other worlds) is in many ways a noble aim, but it has to go beyond giving those non-human creatures the right vocabulary. It must involve a degree of learning on the part of the human too. What if “They Can Talk” ran alongside a project entitled “We Can Hear”, in which pet owners received a briefing in the superhuman capabilities of their animal and intensive training in the particular natural body language of its species?

In 2005, Koko the gorilla was the subject of two law-suits by three former employees of the Gorilla Foundation, who alleged that they had been pressured into revealing their breasts to the gorilla in response to her signing “nipple”. They claimed they were told this was a way to bond with Koko and that their employment would suffer if they refused. The law-suits were settled out of court but it seems likely that it’s a matter of time before a household pet in a study such as Rossano’s presses someone’s buttons in more than a literal sense. How can we accurately decode the information animals are giving us without having an understanding of their own innate social rules?

What if ‘They Can Talk’ ran alongside a project entitled ‘We Can Hear’, in which pet owners received a briefing in the superhuman capabilities of their animal and intensive training in the particular natural body language of its species?

Author Felice Fallon found inspiration in Koko the gorilla’s story for her debut novel, Interviews with an Ape (Penguin). Her fictional gorilla narrator, Einstein, learns to sign by watching two deaf children who work at the circus where he is kept after being separated from his family by poachers. Fallon interweaves Einstein’s story with that of other animals, including an Orca in captivity in a theme park, a pig in a factory farm and a foxhound in a laboratory, with the humans who touch their lives. Without sentimentality, she shines a light on both animal and human misery, reminding us that many humans lead lives we would not wish on a gorilla, a pig or a dog.

Fallon’s hero Einstein ends up in a zoo, based on the zoo in Baghdad, where a kindly keeper realises his secret. When the zoo is devastated by war, Einstein’s being able to sign ultimately saves his life. He becomes the first animal Goodwill Ambassador to the International Union for the Conservation of Nature (while Einstein is fictitious, the IUCU is not). He addresses one of his keepers: “You ask how we are alike, and I will tell you that in every essential aspect we are exactly alike. We want to be safe, to raise our young, to have enough to eat and a place to call home. We are animals just like you. Nothing more and nothing less, and we have as much right to these things and to be here on this earth as you.”

Einstein’s eloquence is the product of a human imagination but it eerily echoes a video speech made by Koko the gorilla to the COP21 summit, an UN-led Climate Change conference held in Paris in 2015.

Sitting in front of a grey backdrop, Koko signs: “I am gorilla… I am flowers, animals. I am nature. Man Koko love. Earth Koko love. But man stupid… Stupid! Koko sorry. Koko cry. Time hurry! Fix Earth! Help Earth! Hurry! Protect Earth… Nature see you. Thank you.”

The nature of the video’s construction – individual signs are strung together with careful editing – is problematic but the Gorilla Foundation’s press release of the time claimed that Koko had been informed about the issues to be discussed at the summit and was genuinely concerned. The press release said: “Koko was clear about the main message: Man is harming the Earth and its many animal and plant species and needs to ‘hurry’ and fix the problem.”

When it comes to teaching animals to “talk”, perhaps there is only one real question. Are we ready to hear what those animals might want to tell us?

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks