Hypersonic weapons: a missile so fast you won’t even see it coming

Coming soon to a war zone near you, terrifyingly fast weapons with no warning, writes Steven Cutts

In 1942 something unthinkable happened. The Japanese army captured Singapore. For the British empire it was the single most devastating defeat ever suffered and, in an historical sense, it was the beginning of the end for the European empires.

Critical to the success of the Japanese operation was the ability of their long-range naval attack aircraft to sink two of Britain’s greatest battleships. For the British it was a truly shattering event. Years later, Winston Churchill would describe his feelings on that day saying that the news struck him almost physically. Lacking any kind of credible air cover, the Royal Navy had attempted to defend itself using tripod-mounted antiaircraft guns fired on visual. The Japanese would loose only a small number of their 88 on their attacking aircraft, no where near enough to save the British from disaster.

Later on in the Second World War, the Americans would do better than this, deploying carrier-based fighter planes whose sole purpose was to protect their fleet against Japanese aircraft. The introduction of the proximity fuse further enhanced their security. Incredibly, the Americans had invented a radar-controlled anti-aircraft shell that detonated at the point of closest approach to its target, boosting the effectiveness of anti-aircraft fire by a factor of five. It was a technology that the British would later borrow in their attempts to shoot down the infamous V1 flying bombs in the closing stages of the war in Europe. It is perhaps best known for its success against the Japanese kamikaze pilots of the mid-1940s.

Realising that defeat was inevitable, senior Japanese officers decided to order their pilots to deliberately crash their aircraft into enemy shipping. This phenomenon has no parallel in the English speaking world and many allied sailers were shocked at this change in tactics. From the point of view of the Japanese high command, it was, however, logical. It had already been recognised that each fully trained Japanese pilot was unlikely to be able to fly more than one or two attack runs against the allied navies before being shot down and there was no guarantee that either of these attack runs would score an actual hit on their enemies. In the circumstances and to the Japanese mind of that era, the logical thing to do was to simply suicide dive your aircraft into the enemy fleet. Such a policy didn’t even need the Japanese to sacrifice their more expensive, high performance aircraft. Many kamikaze pilots set out in substandard, low-cost trainers, although a direct hit on an American aircraft carrier might prove catastrophic for US forces.

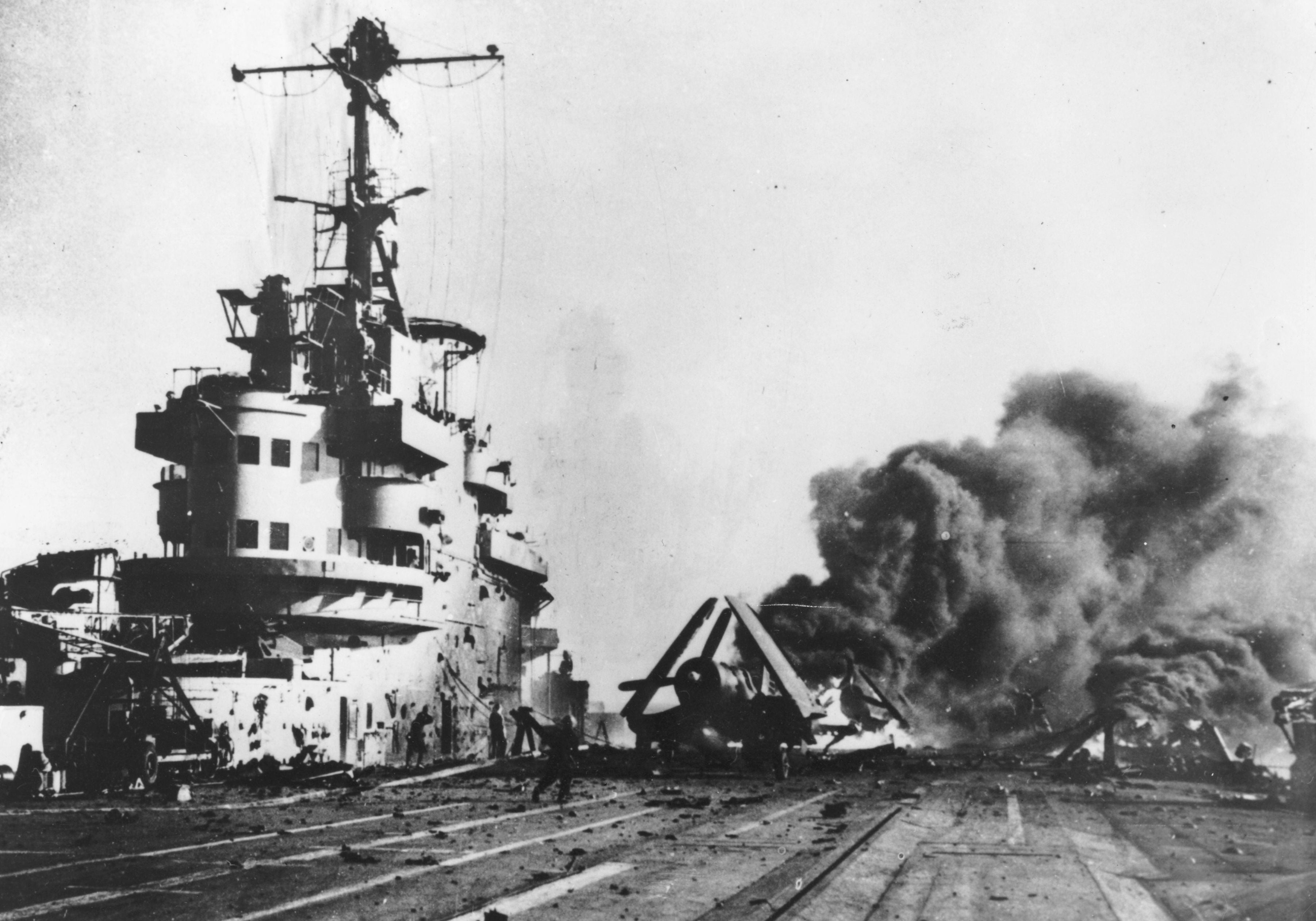

Unfortunately for the Japanese, the American air defence proved much tighter than the Japanese had expected. Only one in five kamikaze pilots hit their targets with the rest being destroyed by fighter defence or ship-based anti-aircraft guns. Nevertheless, 500 allied ships were hit by kamikaze. My own uncle’s ship, HMS Illustrious,survived several hits in succession.

Not all allied vessels were so lucky. In all, 50 Allied ships were sunk, although many more would catch fire and have their performance severely reduced. It’s worth remembering that the Japanese had another 3,000 aircraft adapted for kamikaze service in anticipation of an amphibious landing against the Japanese mainland; although in the event, such an invasion never occurred.

Second World War propeller-driven fighter planes represented a manned missile that charged towards the target at around 300 to 350 miles per hour. In attempting to shoot down these missiles the allies had several problems. One is the relatively small profile of a single-engined one-man aircraft – in practice it’s easier to score a hit on a large aircraft such as a four-engined Lancaster bomber or the American B17 than it is to score a hit on a single-engined aircraft purely due to the small cross-sectional area of the Japanese Zeros. The second is the relatively short period of time that an anti-aircraft gunner has to see the attacking aircraft and open fire. In particular, even the most vigilant of anti-aircraft gunners need to be forewarned as nobody can maintain their concentration for weeks on end on the deck of a ship at sea. The introduction of radar made this task much easier but it remains a basic fact that the faster an enemy aircraft approaches, the less time is available to score a hit on the incoming manned missile.

Most Japanese pilots dived at the Allied vessels to further increase their closing speed and momentum. Nevertheless it is remarkable that the Americans were able to achieve an 80 per cent hit rate. Had the Royal Navy been able to achieve this just two years earlier, the British could have survived the air attack on their fleet and gone on to intercept and destroy the Japanese invasion force that would later capture Singapore.

In effect, air power had transformed naval warfare. This phenomenon would continue through the second half of the 20th century with the introduction of the radar-guided missile. By the late 1960s, French scientists had begun work on a new anti-shipping missile that would become the Exocet. In time they would make a name for themselves selling the Exocet missile to a number of naval and air powers around the world. The weapon scored three hits on the Royal Navy during the Falklands War. The realisation that a third world country could knock out a British destroyer with just one missile was a lesson that sent shockwaves through the entire British government. The Royal Navy had itself already purchased the weapon and senior officers in that organisation must have been aware of its potential.

President Putin in Russia has also made repeated claims that his own armed forces are now in possession of a hypersonic missile that could knock out an American or British aircraft carrier

Part of the reason the British were so vulnerable to the Exocet was the lack of airborne early warning. The radar on an individual ship can only see about 20 miles out to sea. If an enemy aircraft or missile approached at high altitude it will be visible on radar at a much greater range and much earlier than this. Similarly, if the defending force has mounted radar on an aircraft flying at high altitude then an approaching threat can be identified long before it makes contact with the fleet. Modern American AWACS guarding US Navy carrier groups can see more than 300 kilometres out to sea and call up supersonic fighters to intercept the approaching enemy long before it comes within range.

The absence of airborne radar and also the relatively small number of subsonic British harrier jets protecting the taskforce enabled the Argentines to approach and launch their missiles without any visible opposition.

In this scenario the enemy flies towards the fleet at relatively high altitude and picks up the potential target on radar. Remember that a ship at sea is a large slow moving target that has nothing to hide behind. In contrast, the attacking aircraft is a fast moving, small target that can change direction in an unpredictable manner and with great speed. It can also change altitude, dropping to sea level as soon as it has seen its potential, using the Earth’s curvature to hide itself from a ship that it knows to lie ahead. The Exocet missile is then fired blind and instructed to fly forwards with its own on board radar activated. The attacking aircraft then turn around and fly back to their bases while the Exocet approaches its target at an altitude of around 2 metres. After a minute or two, it picks up the enemy ship on radar and proceeds to home in with great accuracy.

Since the end of the Second World War and in the course of 35 years of progress, man had figured out how to build a kamikaze aircraft with no wings where a computer chip rather than a human being plotted its own destruction.

One of the few defensive manoeuvres the British could do in these circumstances was to turn the ship away from the path of the missile. Since all ships are essentially oblong in shape, a ship that attempts to sail in line with the path of the incoming missile is less likely to be hit than one that remains perpendicular to it. The technology of the time also allowed for the use of “chaff”, which is essentially strips of tinfoil that are fired like confetti at either side of the ship in order to reflect radar waves and create additional targets in the mind of the missile. Sometimes this works, sometimes it doesn’t, as the crew of HMS Glamorgan discovered to their cost. They were hit in the closing stages of the battle for the Falklands. In their case a ground-launched Exocet struck the rear of the ship, destroying the onboard helicopter and causing a secondary explosion in the process. Glamorgan was the only British ship to survive an Exocet attack, although 47 Royal Navy sailers were killed. The British had to use so much seawater to extinguish the fire that Glamorgan narrowly avoided sinking with the weight of it. A few weeks later, the vessel sailed back into port to a heroes welcome.

Nevertheless, the Exocet had once again demonstrated an ability to deliver a knock-out blow against a sophisticated opponent. Export orders began to soar and a few years later, the American warship USS Stark was hit in the Persian Gulf by an air-launched Exocet. As with the royal navy vessels in the same class, the Stark was virtually burnt out. This time the Americans had equipped her with a radar and computer-controlled gun that was capable of firing an astonishing number of bullets at the missile during the last few seconds of its approach. On that occasion, and for reasons that were not entirely clear, the gun system was turned off.

One quite important issue to remember in this discussion is that the technology in the Exocet missile was state of the art during the 1980s and only available to a handful of very advanced nations. Today you can buy much better components from the RS Catalogue and quite a few countries have done just that. It is not at all clear how long a fleet of surface vessels could survive in any future war. Even if counter measures were capable of shooting down as many as 80 per cent of incoming Exocet like missiles, an enemy that was equipped with large numbers of such missiles would take a terrible toll of an attacking fleet (at the beginning of the Falklands War, the Argentines had six air launched Exocet missiles).

But military technology is never static and a number of countries are now developing the next generation of anti-shipping missiles capable of being launched from land, sea or air.

The acknowledged leader in this field is China. President Putin in Russia has also made repeated claims that his own armed forces are now in possession of a hypersonic missile that could knock out an American or British aircraft carrier in less than an hour from the moment war is declared.

Most experts agree that a hypersonic missile is one that is capable of flying in excess of Mach 5. Remember that orbital velocity is around Mach 25 although in practice, Mach numbers aren’t a great way to measure the speed of a missile since the speed of sound is effectively an engineering parameter that changes with altitude. In effect sound travels much faster at sea level than at high altitude.

Remember that a kamikaze pilot had a closing speed of between 200 and 400 miles per hour. Now try to imagine a similar unmanned system with a speed of 5 x 700 miles per hour. In the face of a hypersonic missile, the crew under attack would have almost no time at all to respond. As in the Second World War, the defending forces need to be alerted to the possibility of attack and have their defensive systems on standby in order to have any realistic chance of scoring a hit on such a small target. Even in the last few seconds of final approach, a hit on the incoming missile is unlikely to be effective since the resultant debris would continue to hurtle forwards and penetrate the hull of the target vessel.

The tech required to build a hypersonic missile is far from trivial. Recently the British government announced a plan to build a rival hypersonic system, although the UK budget will be small time in comparison to our major rivals. On the other side of the pond, the Americans have flown a few hypersonic test flights within the Earth’s atmosphere, sometimes working in conjunction with their allies in Australia. The total number of flights known to have been performed by their rivals in China is much greater and there is no question that the Chinese are now ahead in this field. Not to be put down, the South Koreans are now also known to be developing their own, indigenous hypersonic missile.

This flurry of activity in the Indo-Pacific region has been brought into sharp relief by the announcement that both Britain and America are about to collaborate with Australia to build nuclear-powered submarines for the Australian Navy. Such a system would dramatically enhance the ability of the Australian Navy to counter any Chinese attempt to advance upon Australia in a future war at sea. While the Chinese are predictably enraged, this trend is already well established, with Vietnam purchasing several state of the art diesel electric submarines to counter any future intrusion of its own waters by the Chinese surface fleet. While China’s numerical superiority in people is undisputed, there are now a number of small to medium sized regional powers that could potentially challenge its hegemony in any future shooting war in the region. These include Taiwan, Japan, South Korea and the increasingly resurgent player that is Vietnam.

That being said, it is unlikely that Taiwan could hold out for any length of time against a full scale Chinese attack unless it was receiving substantial American support. Support of this kind would be critically dependent on the willingness of the Americans to put their fleet in harms way.

Aware of this, Beijing has already introduced early hypersonic long-range missiles along its coastline, some of them with a considerable operational range. The US Navy has reciprocated by changing its pattern of ship deployment and recognising that it would be necessary to operate much further out to sea than previously necessary in any full scale conflict.

Hypersonic flight isn’t easy, especially if you want to use it to score a hit on a target, which by its very nature is loitering at sea level. The air resistance experienced by a missile will increase according to the square of its speed, thus if we had a missile travel at 100 miles an hour at sea level it would experience a significant amount of air resistance and need to be continuously powered forwards by a rocket motor in order to maintain its momentum. However, if the missile designers wanted to increase its speed 10 fold to 1,000 miles per hour, then this would be associated with a 100 fold increase in air resistance. This kind of strategy would also generate immense heat on the surface of the missile due to friction. Beyond Mach 5, most materials used in aviation would already be melting.

Engineers who are experimenting with futuristic scram jet-powered hypersonic missiles usually do so at very high altitude where the air is very tenuous and very high speeds are more credible. Remember that for a satellite in orbit around the Earth travelling at Mach 25 there is effectively no atmosphere anyway since it is already in outer space and therefore there is no drag.

China is now systematically projecting its naval and air capability into the Indo-Pacific region and has no intention of stopping

In contrast, an anti shipping missile is bound to experience enormous drag, especially in the last few seconds before impact. It may also be exposed to unpredictable and high wind speeds during final approach that could influence its accuracy. On a more positive note, the fantastic speed associated with this kind of flight creates a cushion of ionised air in front of the missile that will actually reduce its radar visibility making it even harder for the crew of the ship to see the missile coming. Clever use of the aerodynamics might also enable the hypersonic missile to change course during the final approach to its target creating confusion within the enemy navy.

While a very large vessel such as an American attack aircraft carrier might need to be hit several times in order to be actually sunk, remember that it could effectively be disabled by only one hit. This would especially be the case if secondary explosions on the target caused a large fire. During the closing stages of the Second World War, the USS Princeton was hit by one Japanese iron bomb dropped on visuals by a Japanese pilot who had every intention of surviving his mission. The ship caught fire, 800 hundred US sailers died and the Princeton was lost.

Thus far, there are basically two approaches to the design of a hypersonic weapon system. Some of them are fired vertically upwards like ballistic missiles. These rise up above the atmosphere and proceed to re-enter the atmosphere relatively close to their targets and aerodynamically try to steer towards their targets, although air resistance will tend to slow down the projectile, simply by diving the missile will also tend to maintain or even increase its speed. One question that needs to be asked at this stage is how the attacking force can be sure that there will be a suitable target in front of them, given that the launch site could easily be a thousand miles from the target.

Bare in mind that there are now shoe-box size reconnaissance satellites built from off the shelf components and available for several hundred thousand pounds that will tell you the exact location of almost any surface vessel anywhere in the world. At sea and in the face of modern satellite reconnaissance, there is simply nothing for a ship to hide behind, not even the vastness of the ocean itself.

A second hypersonic missile concept is centred around the use of jet engines or possibly the so-called ram or scram jet engine that achieves active propulsion during the closing stages of flight, not just during the initial rocket propelled boost stage.

Both systems could be pretty deadly especially if they proved to be accurate. It is clear that they would need to carry a war head since the debris itself would carry enough kinetic energy to break through any known hull. Remember that the Exocet missile that hit HMS Sheffield did not explode on impact. Unspent rocket fuel in the motor simply continued to burn in the hold of the ship causing a fire that the crew were unable to extinguish.

During the Falklands War the British learnt many bitter lessons about modern air and naval warfare. Part of the problem they faced was that nobody had fought a war of that kind for several decades and it wasn’t clear at the time how well the various weapons systems would perform. In the event, several British anti-aircraft missiles proved to be woefully ineffective and handheld anti-aircraft machine guns served as a last line of defence against supersonic jets. This kind of improvisation isn’t going to effective against the emerging missile capabilities of a country like Russia or China. China is now systematically projecting its naval and air capability into the Indo-Pacific region and has no intention of stopping. It’s hard to say for sure what the outcome of any future conflict in this region would be but as in the Falklands War it is likely that there would be a number of unpleasant surprises for the various protagonists involved. Without naval superiority, China’s long-held ambition to retrieve Taiwan would be fraught with danger and it is not clear what degree of vulnerability its own surface fleet would be shown to have to the not insubstantial forces that would seek to resist Chinese domination.

In effect, what we are seeing now is the emergence of a new Cold War in a new hemisphere. Exactly how such tensions may play out is hard to say. Very high defence spending could prove to be one of the few factors that could restrain Chinese economic growth in the next few decades and it may well be possible for Beijing to achieve all of its foreign policy objectives by soft power alone.

For the Americans, the ability to knock out Chinese hypersonic missile facilities on the ground and before they get airborne will be absolutely crucial. Reconnaissance satellites in Earth’s orbit have been built so that they can pick up on the infrared signal from a conventional ballistic missile and give significant warning to the Americas. In principle this would enable them to launch their own missiles designed to actually shoot down the incoming offensive system mid-flight. As in the Falklands War, these missiles have never been tested in combat conditions and we remain completely uncertain as to how well they would function in combat. However, hypersonic missiles have a much smaller profile either to infrared sensors or to radar and they are designed to change course dramatically within the Earth’s atmosphere making it much harder to predict their path and target.

Assuming the hypersonic missiles were fired at the Americans or some other friendly fleet, how could they defend themselves? During the final moments before impact, directed energy weapons such as lasers are now being developed to shoot down the incoming missile although the time available for such action will be vanishingly small. Given the modern day reluctance to sacrifice American service men and women in combat, this task would probably be attempted using unmanned cruise missiles fired from a great distance before the US Navy capital ships could be placed in harm’s way.

Not to be outdone, the government of North Korea is believed to have launched a new hypersonic weapons system that has managed to raise eyebrows in the western intelligence agencies. Hwasong-8 appears to be a prototype for exactly the kind of near unstoppable anti-shipping missile the Americans have feared for so long. For those of us who remember the anxious moments of the 20th-century Cold War, it all sounds very familiar.

Renewed American investment in anti-missile counter measures and their own hypersonic missile tech now seems inevitable.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments