Will hip resurfacing be a renaissance in ceramic or just another fad?

It worked for Andy Murray, so why isn’t hip resurfacing offered to more people as an alternative to the replacement? Orthopaedic surgeon Steven Cutts explains

All my life, I’ve wanted a British player to win the Wimbledon men’s singles final. When I was very young, I remember Christopher “Buster” Mottram playing. He was England’s number one player who reached 15th in the world in 1983 – but he never won Wimbledon. Instead, for most of my life, usually when it came to the final, a couple of foreign players would stroll on to court and the audience would politely applaud before the pair did battle for the title.

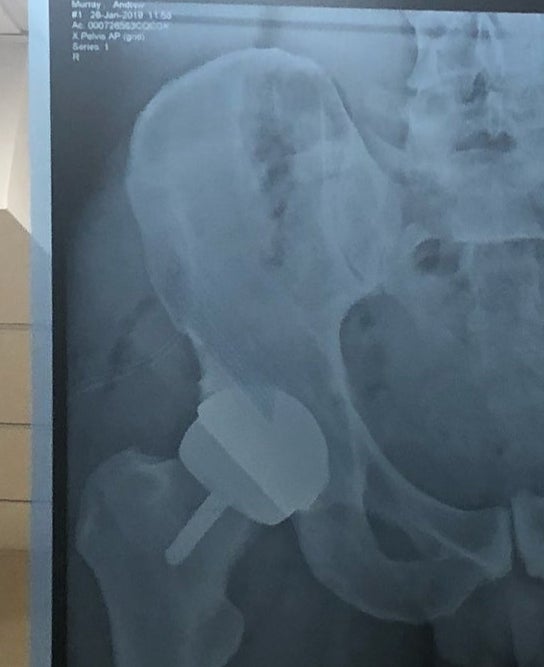

Then, after a 76-year hiatus, Andy Murray made us proud. It looked like we finally had a player in the top four when – quite suddenly – he started to develop hip arthritis. In another age, he might have been forced to give it all up but this was the early 21st century and Murray decided to take his chances on the operating table. Better than that, he asked a prominent London surgeon to give him a “Birmingham Hip Resurfacing”. It worked, and Murray is still in the game.

Is he still going to be grateful in 10 years’ time? Well, maybe that’s a question for another day, but it does illustrate what kind of result can be achieved – albeit in a performance athlete – using the hip resurfacing concept, and, incredibly, hip resurfacing as we know it today was actually pioneered in this country. So how then can the world of orthopaedics offer this same technology to a broader spectrum of patients?

The vast majority of hip replacements aren’t “resurfacing” but the idea of resurfacing is hardly new. The late Sir John Charnley – one of the founding fathers of the modern hip surgery – actually experimented with hip resurfacing in the 1960s before been beaten back by a poor choice of materials. He was using Teflon and they all fell to bits. In spite of this, Charnley managed to stage a comeback fight with a metal on plastic articulation. His prosthesis uses a lengthly stem, a polyethylene cup and an astonishingly small metal femoral head. They’re cheap, they’re easy to put in and they still work. Very, very well.

In fact, quite a few of the landmark products were developed in the UK, usually by small groups of highly motivated individuals working without government support. If we look at the results of the modern “Exeter” hip replacement, we see a device that emerged in the early 1970s and is still in use to this day. While the overall product is regarded as successful, the stem on the Exeter Hip replacement in particular does extremely well with one report suggesting a 97 per cent survival rate at 30 years.

Part of the challenge of inventing a new hip replacement is the quality of the competition. For the whole of human history, we had nothing that could replace the hip joint. Then, around 197, we were suddenly blessed by a mass of successful implants. In summary, when it comes to hip replacements, the bar is set very high and it’s not at all easy to convince a jobbing surgeon that it’s worth giving up on an iconic implant and switch to something new.

And yet there are people trying to persuade us to do exactly that, pretty much all the time. In this country alone, we now perform more than 100,000 hip replacements each year. If we’re looking at a 5 per cent failure at 20 years then we’re looking at 5,000 people who need complex and difficult surgery, often at a very advanced age. Quite apart from the human cost, the economic burden of revision surgery ought to be driving us to improve on our current results.

Given the sheer scale of the research budgets, it’s slightly surprising that historical products like the Charnley and the Exeter are still in use. Part of the problem is cultural. Within the industry, there is a strange dichotomy between people who are continuously fighting to get ahead of the competition and who live in fear of anything that might be seen as new. If we insert an unproven prosthesis into an unsuspecting patient then we are consciously denying them access to a more well established product that we know for sure has a 96 per cent chance of lasting 10 years. At the same time, we are also giving them something about which we have no knowledge whatsoever.

Few, if any, of our modern hip replacements are very much better than the devices that emerged in the early 1970s

Modern hip resurfacing technology emerged in the late 1990s in Birmingham. It was based on a “metal-on-metal” implant and for a number of years it was disdained by the British orthopaedic community. Then there was some sort of a bizarre tipping point. One day hip resurfacing seemed too new fangled for general use. Then almost the next day it was the best thing since sliced bread. It seemed every manufacturer in the world started to sell their own version of a metal on metal hip resurfacing. Most if not all of these implants bore a striking resemblance to the product popularised in Birmingham by Derick McMinn, an orthopaedic surgeon with a special interest in hip replacements. With the benefit of hindsight, they were overdoing it. Most of the copycat products would be dogged by early failures and promptly withdrawn from the market. The original Birmingham product proved to be iconic and is still used by some surgeons, admittedly on a much smaller scale than in the recent past.

The idea of a metal-on-metal joint surface was also tried in more conventional hip replacements and seemed to do well at first but, in time, it was eventually withdrawn in the face of mounting failures. Many orthopaedic surgeons were critical of the whole experiment but some were more forgiving. I bumped into a chap I had trained under in Leeds and he had this to say about the whole metal-on-metal fiasco: “Hindsights a gobby little bastard but he’s never around when you need him.”

Broadly speaking I would say that this statement is true. What’s good for Andy Murray ought to be good the rest of the population and at one stage about a quarter of the hip replacements in Australia were metal on metal devices of a type developed in Birmingham. We seemed to be on the threshold of a new era. I can still remember sitting in the Doctor’s mess at the Royal Orthopaedic Hospital in Birmingham chatting about buying shares in the hip resurfacing factory. The clinics were packed with satisfied patients and from our own perspective, we were awash with insider knowledge. If I’d ever had any money in the first place, I could surely have made even more money by buying shares in the sort of companies that made hip resurfacing. But it was not to be.

Medicine and big business are a difficult and sometimes febrile combination and in reality many orthopaedic implants have a similar trajectory to the metal-on-metal/hip resurfacing story. The early results look good. But then we reach an inflexion point where everyone leaps on the band waggon and then – at some ill-defined date in the future – there are rumours of failure.

Central to our collective anxiety about resurfacing is the issue of metal ions. Since both sides of the joint in a resurfacing were made of a special metal, the debris that stems from walking was quick to dissolve in the body. In time, the concentration of several metal ions begins to soar. Needless to say, the kidneys have something to say about this and turn out to be rather good at clearing our blood. But since each and every step that a hip resurfacing patient takes will generate additional debris, the background level of metal ions is never going to fall.

Remember that hip resurfacing was consciously marketed as a solution for younger patients. In the blink of an eye, large numbers of women of child-bearing age were soon living with massively increased levels of cobalt and chrome ions. As soon as one of them gets pregnant – and in time many of them would – what would be the impact on the developing foetus? In fact, there’s quite a lot of evidence that successful pregnancy can be achieved even in the presence of elevated metal ions, but as soon as the element of doubt enters your mind, the product becomes a no-no for 50 per cent of the young adult population. Worse still, a tiny number of patients seemed to develop a bizarre soft tissue reaction sometimes referred to as “pseudo-tumours”. It’s a phenomenon I first stumbled across myself in the early days of the hip resurfacing project and at the time, I just assumed it was freakish. It wasn’t and the Oxford Group would later publish a series of about a dozen of their own cases with the same problem.

Unless we want to be stuck with imperfect products forever somebody somewhere has to be willing to stick their neck out and accept the risks that inevitably come with innovation

Some people were aghast by the emergence of the pseudo-tumour phenomenon. Others, such as the world famous Sarah Muirhead-Allwood, were less surprised. As a junior registrar in Norwich in the 1970s, she had watched one of the earlier metal-on-metal joint replacements pass through exactly the same arc and recalled exactly the same soft tissue reaction occurring in a good number of patients. Between that era and the 1990s there had been dramatic advances in manufacturing technique and our results are much better than they used to be but in some respects, that just didn’t matter. We had simply revisited the same materials and obtained the same result.

A while ago now, I got talking to a prominent colleague at a conference in New Orleans. He gave me this, rather sobering assessment: “Every time you attend a medical conference they list a mass of new advances in the field. Hold that idea in your head right now and listen to my next sentence. Outcomes in orthopaedics haven’t changed at all in the last 40 years. What are the people at this conference actually talking about?”

Incidently, this isn’t true. There have been plenty of advances in orthopaedics in the last 40 years, but it’s almost true. Fractures don’t heal any faster now than they did in the 19th century. We still don’t have a disease modifying agent of a condition as common as osteoarthritis and few, if any, of our modern hip replacements are very much better than the devices that emerged in the early 1970s.

It would now be regarded as taboo to put metal-on-metal hip resurfacings into women at all and the indications for men are very narrow. And yet – in spite of everything, the resurfacing concept continues to appeal. Still undefeated, Derrick McMinn is developing a hip resurfacing concept using a plastic liner on the socket. Maybe if he eliminates the direct contact between two metal surfaces then the whole project could be rejuvenated. Another promising contender is the “Adept Hip Resurfacing”. The Adept is one of the products that tried to jump on the resurfacing bandwagon and – remarkably – it’s still in the game. Results in the major joint registries are similar to those achieved by the original “Birmingham”.

If you think hip resurfacing is a good idea and you’re worried about the metal ions why not do away with the metal thing altogether and make exactly the same product out of ceramic?

Ceramics have been used in orthopaedics for many years now and while some of the early products could let you down – they used to shatter when someone fell over – the more recent incarnations are much more effective. What would happen if we manufactured a hip resurfacing product where both sides of the joint are made of a ceramic? Answer: we’d end up with a product like the “ReCerf”, which was recently touted at the Bristol Hip meeting as the next best thing since the Birmingham Hip Resurfacing.

According to the manufacturers, ReCerf has already been put into over 500 people. It sounds great, but for those of us who have played this game before, these numbers don’t stack up. It’s going to take a lot more than two years of follow up and a few hundred cases to convince the modern orthopaedic community that resurfacing is worth another try. This sort of work is best done by enthusiasts in super-specialist centres where the patients have been lectured at length on the experimental nature of what they are about to take on.

Unless we want to be stuck with imperfect products forever somebody somewhere has to be willing to stick their neck out and accept the risks that inevitably come with innovation. In the 1960s this task was performed by the likes of people like Sir John Charnley. Yes, he got egg in his face with the Teflon but that didn’t stop him. He kept going and bequeathed us a classic.

More recently, McMinn and his co-workers have taken the same burden onto their own shoulders, and in expert hands and with carefully selected patients the Birmingham hip resurfacing still does very well. The thousands of people requiring hip revisions every year cannot be regarded as acceptable collateral damage forever, and we have to keep looking for something new. If we want something that can be implanted en masse by ordinary surgeons in ordinary hospitals – with significantly improved results – somebody somewhere is going to have to take risks again.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments