Have we fallen out of love with e-readers?

While Amazon gets ready to launch a new Kindle, Caroline Corcoran is one of a growing number of people who are going back to books

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

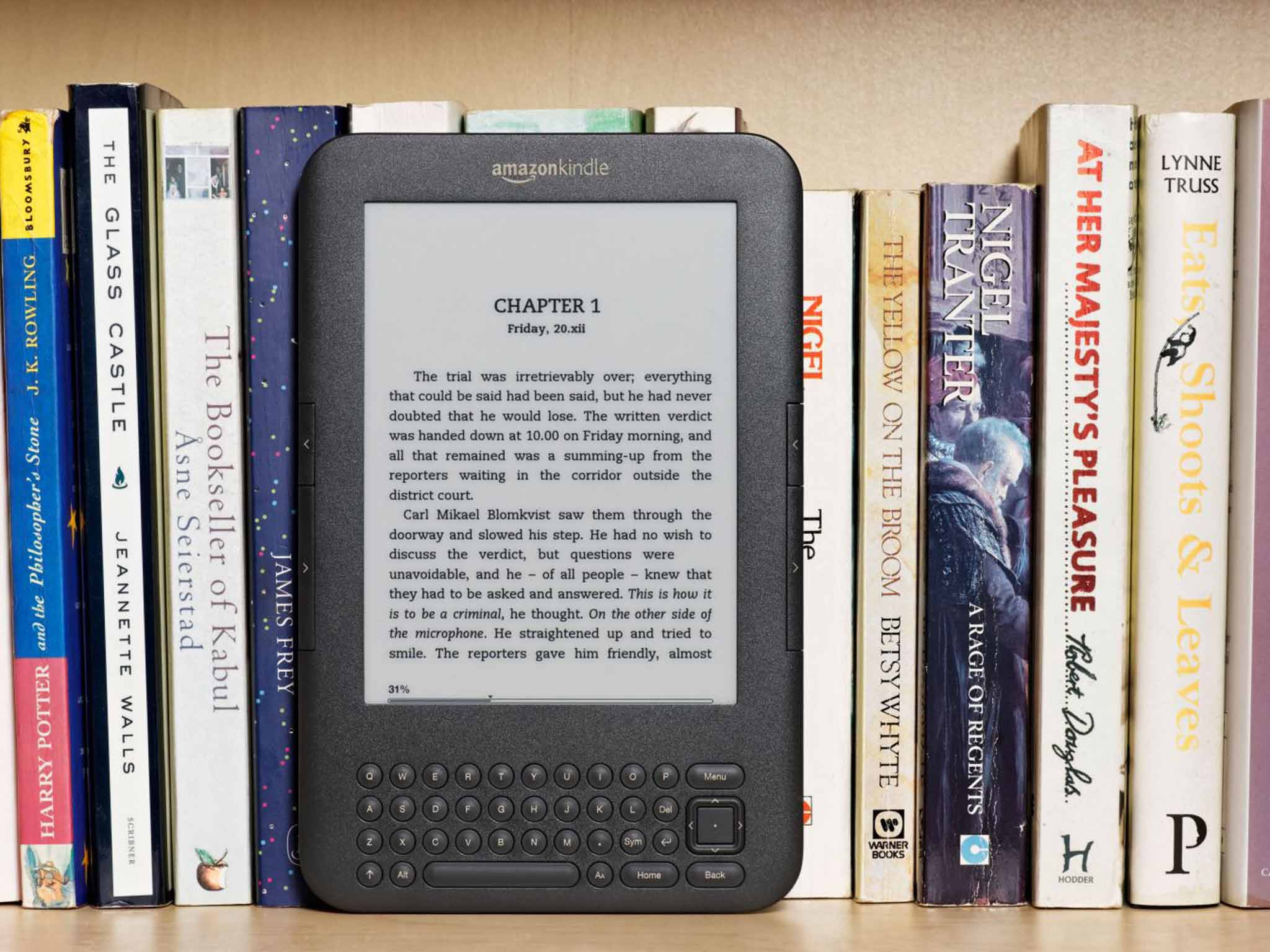

Your support makes all the difference."Print is where words go to die." So went the theory in 2007 when Amazon launched the Kindle. In fact, so sure was the world that books were dead that when Ikea redesigned its ubiquitous Billy bookcase in 2011, it was thought to be so that it could accommodate knick-knacks rather than "archaic" paperbacks.

But while it's true that e-books show no signs of disappearing – the new Kindle Voyage launches next month hot on the heels of the "Kindle Unlimited" subscription service that came to the UK last month – neither does print.

Recently, I realised that I had become so addicted to the speed of new book buying on my Kindle that I had barely bought anything in print in the past year. I had read Americanah and The Luminaries and tens of others on my e-reader, and I was sad that such great books were missing from my bookshelves. Worse than that, though, was a feeling that plots had started to blur, even with books that I had loved. The only way I could explain it is that they had never had a physicality. Not like the black and gold cover of The Secret History, or its weight when I picked it up from my bedside table.

So I decided to go back to books. On my first trip to Waterstones, I left with a hardback of the new Howard Jacobson that there is absolutely no way I can take on the bus. But I don't care – somehow a story like that should have weight, and it feels so luxurious to get into bed and prop up that beast of a dystopia on my knees.

In 2013, British consumers spent £2.2bn on print, compared with just £80m on e-books and last November, statistics by the Association of American Publishers showed that adult e-book sales were up just 4.8 per cent in a year, while hardcover book sales had risen by 11.5 per cent. Nielsen BookData analysis showed e-book sales in May and June last year fell by 26 per cent from 2012.

So have Kindle converts returned sheepishly to the book shop? And if so, why? The theory that the e-book reading experience simply isn't rich enough is a popular one. There is no "book smell"; no rustle of pages that can't be turned quickly enough.

One study showed that in a group reading the same book, e-readers had a lower plot recall, which was credited to a lack of "solidity". When we can't see the pile of pages growing on the left and shrinking on the right, the book is, apparently, less fixed for us.

Scott Pack, publisher at HarperCollins imprint The Friday Project, isn't surprised. "I retain a very physical memory of a book for some time after reading it," he says. "I can recall whether a particular scene or quote appeared on the left- or right-hand page, towards the top or bottom, and sometimes the page number, too."

In September this year, The Bookseller conducted research that found nearly three quarters of 16- to 24-year-olds preferred print to e-books and when asked why, the sentence "I want full bookshelves" cropped up, bringing to mind Tracey Emin and Damien Hirst's recent "shelfies" at the London Art Fair. What better route into people's minds than via their bookshelves? Piled up Lonely Planets, a well-thumbed Maya Angelou... our personal libraries give an insight into who we are. And if our bookshelves stop being updated, we may be eternally identified by our university penchant for Mills & Boon, even if most of what we have read in the past five years is contemporary American dystopia.

"I believe the reader of 2020 or 2030 will have two libraries, print and digital, with different types of books and publications in each," agrees Scott Pack. "While I have no qualms about trying out a debut author on e-book or loading up some holiday reading on to my Kindle, when it comes to my favourite authors I have to own the print edition, and I remain a sucker for a beautifully designed and printed book."

Somebody had better tell Ikea to redesign that Billy bookcase again.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments