Google’s image recognising robots turned on themselves, making weird dreams that could show why humans are creative

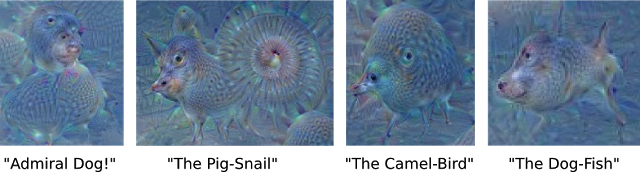

'Admiral dog!' and 'The Pig-Snail' could be clue to creative process for robots and humans

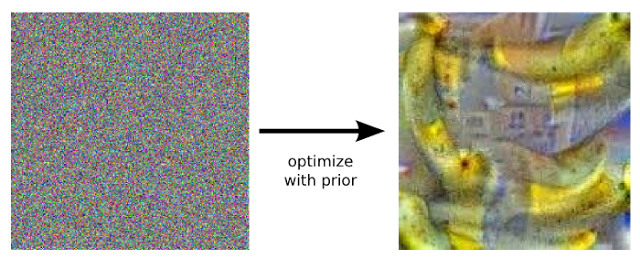

Computers have dreams, according to Google — and they’re often highly trippy, strange ones of dog-fishes and bananas.

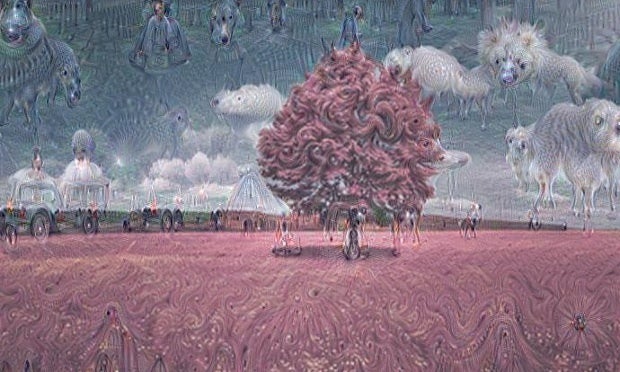

Google’s highly-powered, clever computers are normally used for image recognition — a technology that requires computers to think like humans, learning what things look like. But the company set them loose identifying small, subtle things, skewing the images to show a knight made of dogs or clouds that resemble a “pig snail”.

The search giant is just one of many companies who are working on artificial neural networks, which use highly-developed mathematical methods to simulate the way that human’s brains think. But by turning those computers upside down, they throw out the strange images.

Such computers work by being trained — showing them millions of examples and gradually adjusting the computer to teach it when it makes mistakes and what it should do instead. They are a series of layers, so that the image is fed into the first, which is then passed through the 10-30 layers which gradually build up an answer to what the image is.

The first layer might pick out the corners or edges in a very general way, for instance. But then it will pass that information on to the next layer, which might see that those edges belong to a door or a leaf. And then the last layers will put each of those bits together, putting the different things that have been recognised into an overall image like a forest of leaves or a building.

But to see what the robots might turn up, Google sent images back the other way — telling it what to see at the final layer, and allowing it to do the work to spot that in an otherwise unrelated image. By doing that, Google’s researchers found that the networks don’t just spot images, but can actually generate them, seeing things in pictures that aren’t really there.

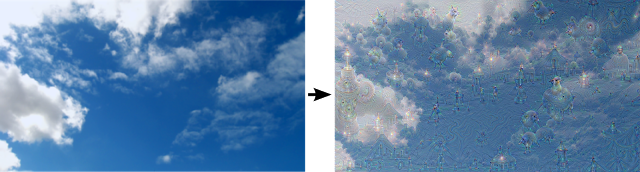

To push the machines further, Google told the robots to amplify and over-interpret images, so that whenever they thought they spotted something, they were told to make it more like that. So the robot might look at clouds, see one that looks like a bird, and then make it look even more like a bird — meaning that the robots would get into feedback loops, amplifying what they’d seen over and over.

The researchers hope to use the information found to understand more about how the algorithms work. So, for instance, researchers can find out what level of abstraction the robots are thinking of images at, and explore how much the network has learned.

And the information could eventually be used to understand more about humans, too.

“The techniques presented here help us understand and visualize how neural networks are able to carry out difficult classification tasks, improve network architecture, and check what the network has learned during training,” wrote three Google software engineers, Alexander Mordvintsev, Christopher Olah and Mike Tyka, in their post about the findings. “It also makes us wonder whether neural networks could become a tool for artists—a new way to remix visual concepts—or perhaps even shed a little light on the roots of the creative process in general.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments