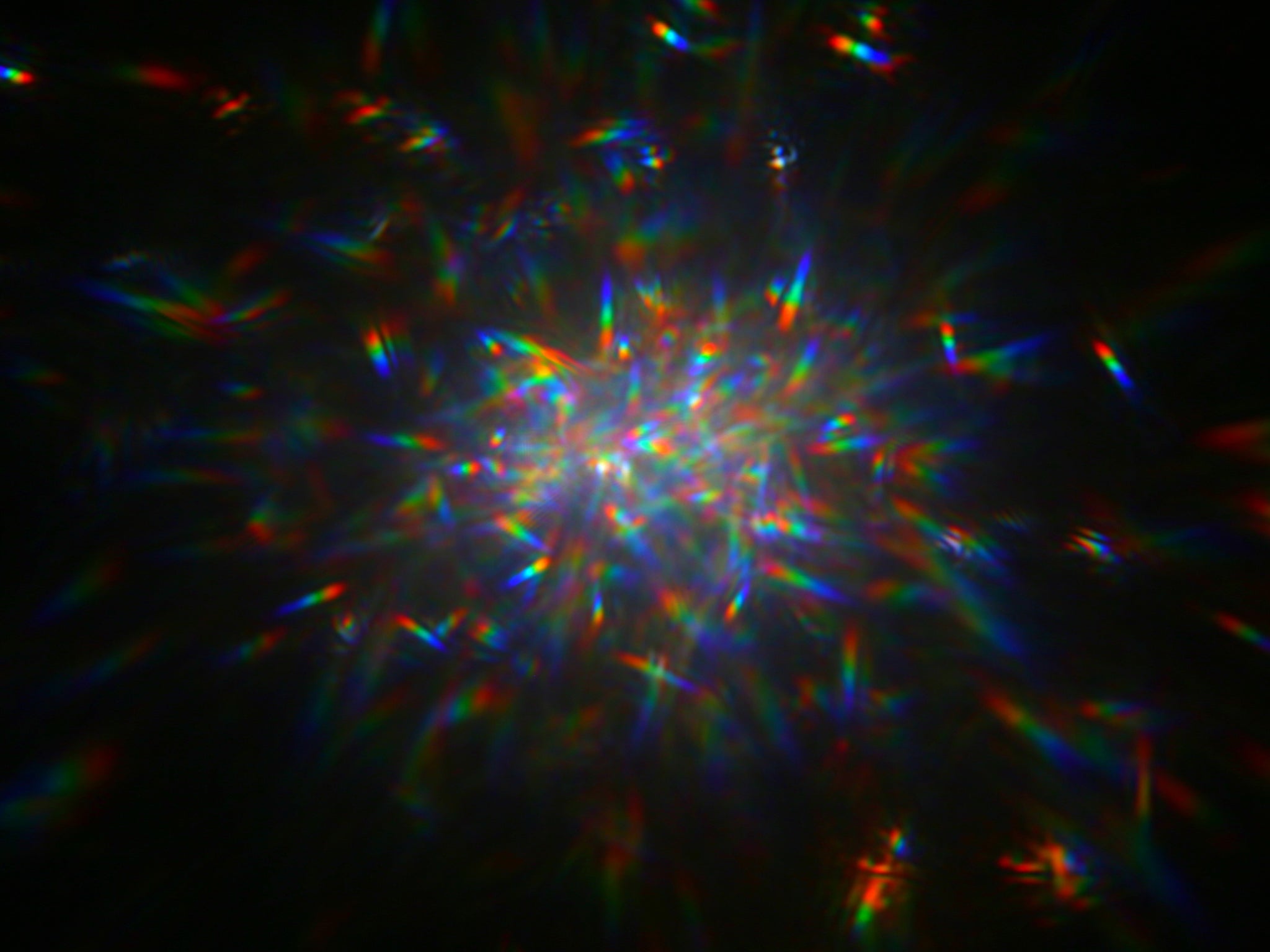

Glitter could power the telescopes of the future, says Nasa, as it launches 'Orbiting Rainbows'

The ‘Orbiting Rainbows’ system could replace the huge and expensive mirrors required in telescopes at the moment

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Nasa is looking to use glitter to take images of the new worlds it is exploring, it has said.

The huge mirrors that the agency currently has to build for its telescopes are expensive and difficult to construct, and their giant size can make it difficult to launch them into space. But using glitter-like material, as part of a project called Orbiting Rainbows, could cut down on those costs considerably.

The new telescopes will put a cloud of the shiny particles into telescopes, which would still allow for the same high-resolution images.

"It's a floating cloud that acts as a mirror," said Marco Quadrelli from Nasa’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory, which is exploring the project, the Orbiting Rainbows principal investigator. "There is no backing structure, no steel around it, no hinges; just a cloud."

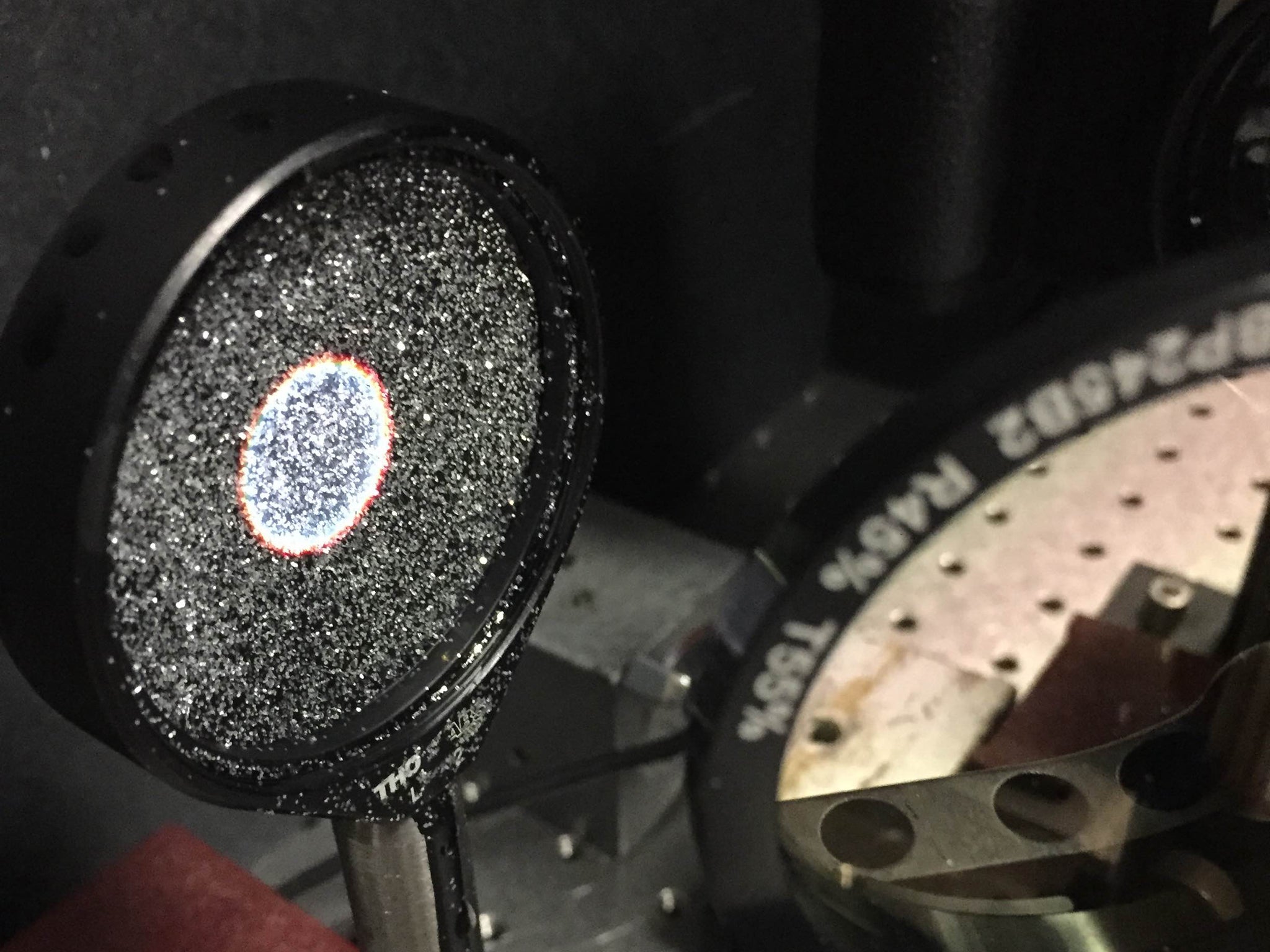

The system would use laser beams to manipulate the cloud of glittery grains. Those beams would be able to trap the tiny particles, because the energy from the light both pushes them away and pulls them towards the beam. That would push them to align in the same direction, making the cloud of grains into a reflecting surface.

By trapping the glitter once it is up in space, scientists would be able to send the telescopes up out of the Earth’s orbit much more easily. Scientists would be able to send the cloud out into space, before trapping it using lasers and forcing it into the right shape.

But that cloud would still be less smooth than one single mirror, so the images would have more noise. So scientists are now working to develop computers that could remove the noise generated by the fact that the image would be coming from many tiny mirrors.

Even if that is not overcome, scientists might still be able to use the technology to send back raido messages. The wavelengths of those are much longer than the of images, so the glitter grains don’t have to be as precise.

Scientists hope to eventually send some of the glitter out into low-Earth orbit — making a telescope about the size of a bottle cap — to see whether it would work.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments