Giant comets hovering on the edge of the solar system pose a much greater risk to life on Earth than we thought, scientists say

The list of potentially destructive rocks should be increased, the scientists recommend, and humanity should do better to keep a closer eye on

Earth could be at much greater risk of a comet strike than people think, according to a new report by scientists.

A whole set of previously underestimated comets sitting at the edge of our solar system might actually make their way here and collide with us, the scientists have warned.

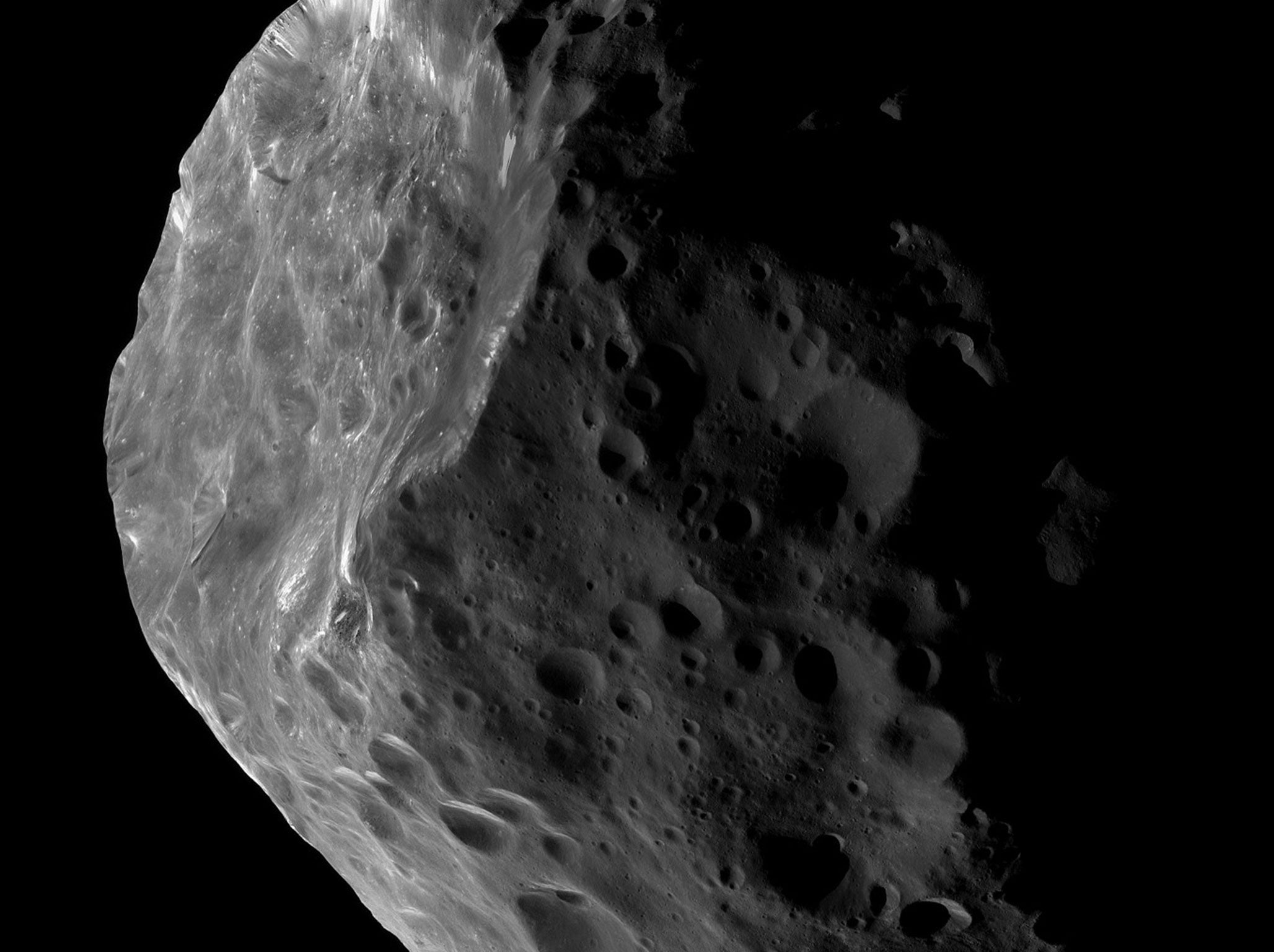

Usually, scientists look at the asteroid belt that sits between Mars and Jupiter when seeking out potentially dangerous rocks. But scientists have also discovered a huge set of “centaurs” — giant comets that should be added to the list of rocks that we are worrying about, according to the scientists.

None of the rocks is thought to pose any immediate threat. But while collisions are rare they could be a huge problem — previous collisions with one of them might have wiped out the dinosaurs, the scientists say.

The comets move around near the outer planets Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus and Neptune. But roughly every 40,000 to 100,000 years they are nudged off course and into the path of Earth.

If one of the Centaurs got to Earth it would probably get broken up into dust and bigger bits, unleashing a huge amount of debris, some of which would almost certainly hit Earth.

The scientists say that some of the biggest environmental upheavals in the history of the earth could have been caused by the comets. Those behind the research suggest that it should be a warning that we should keep a closer eye on the more distant comets in case they become a hazard.

"In the last three decades we have invested a lot of effort in tracking and analysing the risk of a collision between the Earth and an asteroid,” said Professor Bill Napier from the University of Buckingham, one of the authors of the research, in a statement.

“Our work suggests we need to look beyond our immediate neighbourhood too, and look out beyond the orbit of Jupiter to find centaurs. If we are right, then these distant comets could be a serious hazard, and it's time to understand them better."

The research team included scientists from the University of Buckingham and Armagh University. The research is published in Astronomy and Geophysics.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments