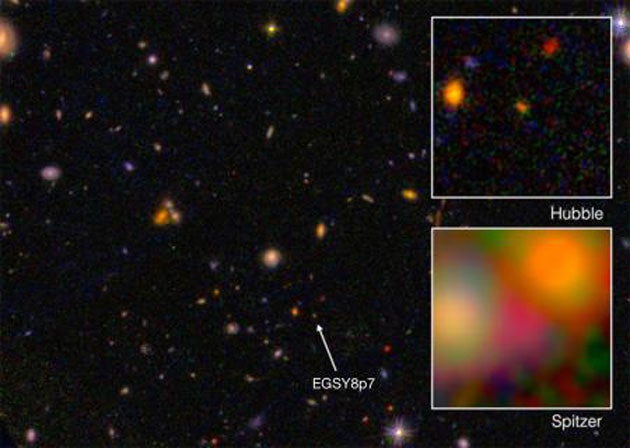

Furthest galaxy from Earth found and is nearly as old as the universe

The galaxy, known as EGS8p7, shouldn’t even be able to be spotted according to existing theories

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Scientists have found the furthest galaxy from us ever to be spotted — and it’s not much younger than our universe.

The galaxy shouldn’t even have been able to be spotted, according to existing theories. And scientists are now trying to work out why exactly they can.

Known as EGS8p7, the galaxy is 13.2-billion years old. The universe itself is 13.8-billion years old.

Usually, scientists measure the distance to old galaxies using redshift — an effect that means that light is stretched as it travels and becomes redder. The amount that happens is a measure of how far away it is.

But that technique can’t be used for the objects that came into existence with the very earliest universe. The early universe couldn’t transmit light, because it couldn’t move through the cosmos, and the radiation emitted by young galaxies would have been absorbed by clouds of atoms.

That should mean that in theory there shouldn’t be any way of seeing the newly-discovered galaxy, EGS8p7. But scientists can.

"The surprising aspect about the present discovery is that we have detected this Lyman-alpha line in an apparently faint galaxy at a redshift of 8.68, corresponding to a time when the universe should be full of absorbing hydrogen clouds," said Richard Ellis, a professor of astrophysics at University College London, said in a statement.

Scientists are now trying to work out how exactly they can see it.

"The galaxy we have observed, EGS8p7, which is unusually luminous, may be powered by a population of unusually hot stars, and it may have special properties that enabled it to create a large bubble of ionized hydrogen much earlier than is possible for more typical galaxies at these times," Sirio Belli, a Caltech graduate student who worked on the project, said in a statement.

The findings might mean fundamentally changing our understanding of the early universe.

"We are currently calculating more thoroughly the exact chances of finding this galaxy and seeing this emission from it, and to understand whether we need to revise the timeline of the reionization, which is one of the major key questions to answer in our understanding of the evolution of the universe," Adi Zitrin, a Nasa Hubble Postdoctoral Scholar in Astronomy, said in a statement.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments