French left loses its head over Robespierre game

Politicians claim portrayal of a leader of the Revolution as a barbarian is a capitalist plot

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

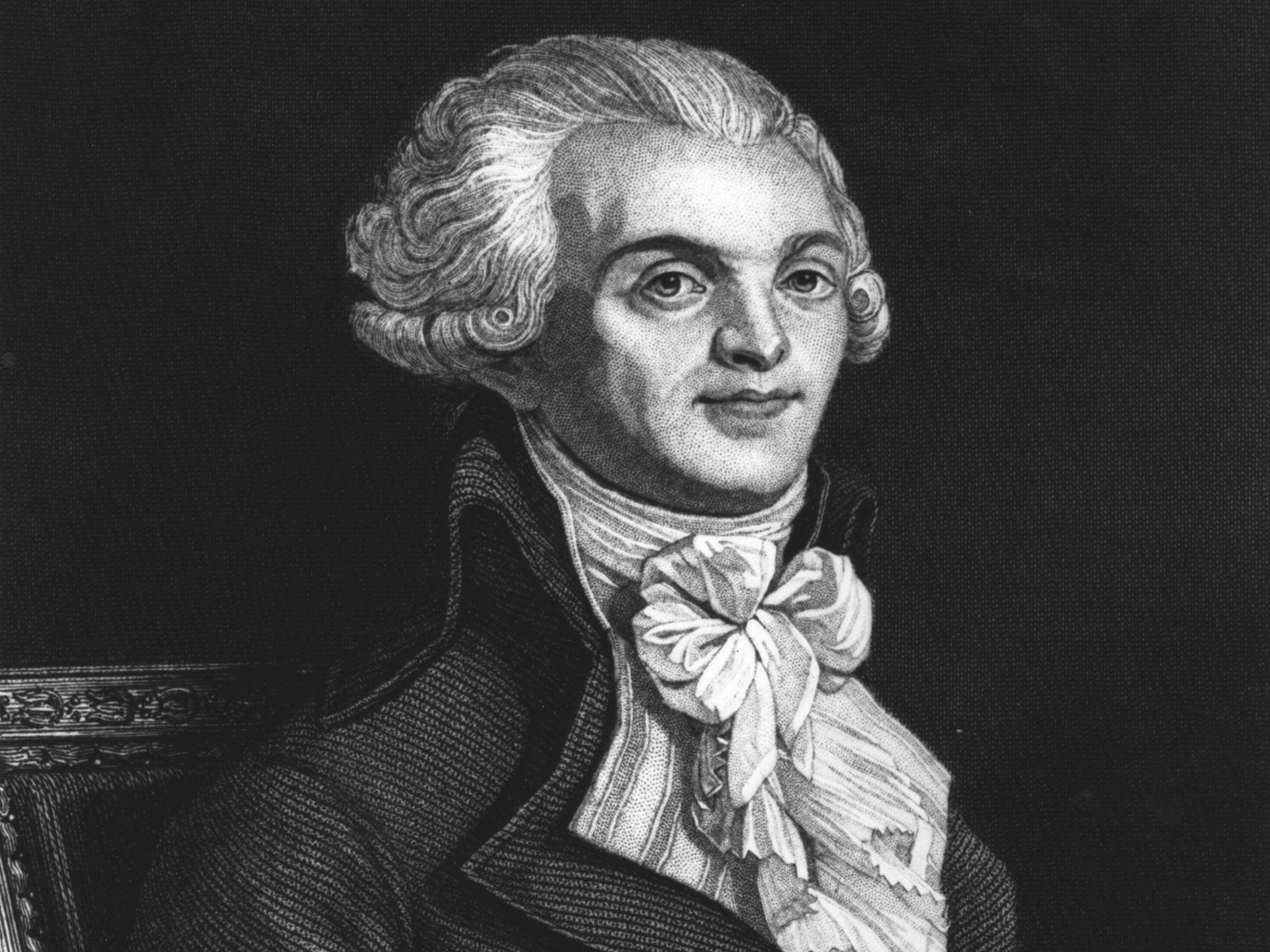

Your support makes all the difference.More than 200 years after his head was chopped off, Maximilien François Marie Isidore de Robespierre is still causing trouble.

The latest in the popular Assassin’s Creed series of video games presents the French revolutionary leader as a blood-thirsty psychopath. He was, after all, directly or indirectly responsible for more than 40,000 executions in 11 months during the “Terror” of 1793-94.

Cue apoplectic fury on the French hard left, which reveres Robespierre as a “man of the people” and a “father of democracy”.

“This is propaganda against the people,” said the Euro MP and former presidential candidate, Jean-Luc Melenchon. “The people are [shown as] barbarians, as bloody savages. A man who was our liberator at one stage of the Revolution is portrayed as a monster.” Mr Melenchon says that the game Assassin’s Creed Unity, released last week by the French production company, Ubisoft, is part of a capitalist conspiracy. “They are insulting us to destroy what keeps us together as French people,” he said. “This is a rewriting of history to glorify those who lost and to discredit the Republic, one and indivisible.”

The makers of the game admit that some events have been exaggerated and liberties have been taken with some facts. The revolutionaries are shown waving the French tricolour in 1792, before it was adopted. They sing the “Marseillaise” before it became the national anthem.

Antoine Vimal du Monteil, the game’s producer, said: “Assassin’s Creed Unity is a game for the mass public. It is not a history lesson.”

Another left-wing politician – and historian – argues, however, that many young people learn their history from games, rather than books or films. Alexis Corbière, secretary general of La Partie de la Gauche (the party of the left), says that the game “alleges wrongly that there were hundreds of thousands of deaths [in the Terror] and that whole streets were filled with blood”. He has called for a “public debate” on how history is portrayed to the young.

Thousands of people did die in the Terror – not just aristocrats but many revolutionaries and ordinary people suspected of disloyalty, including, finally, Robespierre himself. The game’s claim of “hundreds of thousands” of victims is excessive.

Right-wing and more moderate left-wing politicians have mocked the anger of Mr Melenchon and the hard left. One conservative commentator suggested that it was like starting a political debate on how America is presented in Batman Begins. Others have suggested that Mr Melenchon’s anger would have been better directed against the violence of the Assassins’ Creed series.

The argument does draw attention, however, to a persistent ambiguity in French attitudes to the Revolution of 1789-94 and the Napoleonic empire. Much of the political structure and law of modern France can be traced to this period. French children are taught that the French Revolution – not the American Declaration of Independence and not the Industrial Revolution in Britain – was the true beginning of modern times. How, then, to deal with a man like Robespierre, a lawyer who began by opposing the death penalty and then sent hundreds to the guillotine?

Robespierre’s apologists suggest that he had wrongly been blamed for the Terror which was more a case of mass hysteria than the work of one man. His speeches portray him as a monstrous prig and a priggish monster. He argued that even those people vaguely suspected of wanting to slow down the Revolution – even if they had not yet spoken or thought it – should be killed for the “public good”. The new Assassin’s Creed game manages to monster him even further. He is presented as a psychopath and (shades of The Da Vinci Code) a man who wanted to restore the ancient power of the Knights Templar. His character says at one point: “I detest this filthy world which is nothing but a carcass on which mankind feeds like worms… I want to kill as many people as possible… My genocidal crusade begins here and now.”

This is crude – and arguably less scary than the creepy subtlety of the real Robespierre. His arguments for the absolutism of the people’s rights presaged Stalinism or Maoism. “If virtue be the spring of a popular government in times of peace, the spring of that government during a revolution is virtue combined with terror: virtue, without which terror is destructive; terror, without which virtue is impotent. Terror is… then an emanation of virtue… The government in a revolution is the despotism of liberty against tyranny.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments