The fact is we take skin immensely seriously, but when and why did this start?

Skin has become a global preoccupation. We describe things as ‘skin deep’, and while we’re not supposed to judge a book by its cover, we do. Andy Martin explains how this came to be

His real name, if I remember correctly, was Connelly. But in fact everybody called him “Lizard Man”. There are two important things you need to know about Lizard Man: one, that his skin was scaly, hence the moniker; two, that he had a heart of gold and was kind to animals, children and old ladies. Sadly, the one thing that everyone picked on was the scales. Lizard Man, by our standards, was one ugly human being, and never failed to arouse a degree of revulsion from passersby.

So one fine day he is waiting for a bus. As usual he has his hat pulled down, his collar pulled up, and a scarf wrapped round the lower portion of his face. Just enough nose showing to breathe. And he has dark glasses on too. Even so, there is no one else at the bus stop waiting with him since anyone else has done a runner, revolted by the sight of him.

The bus arrives and he hops on. Lizard Man notices that it doesn’t seem to be going his usual route. He is even more surprised when it takes off, like a plane, and then, going up a few gears, flies through outer space and lands on a planet in a galaxy far, far away. Lizard Man is welcomed like a hero by the beautiful beings who populate this other world because he is recognised as having the most radiant soul in the universe. They do not notice the scales. They see only the inside not the outside.

Of course, it was only a story, one I read many moons ago, in a comic called Astounding Stories. I think Lizard Man ended up emperor of that far-off planet, adored by all. Pure fiction. A fantasy. But the bit that is not in the least fantastic is the part about Earth. That is exactly how earthlings behave.

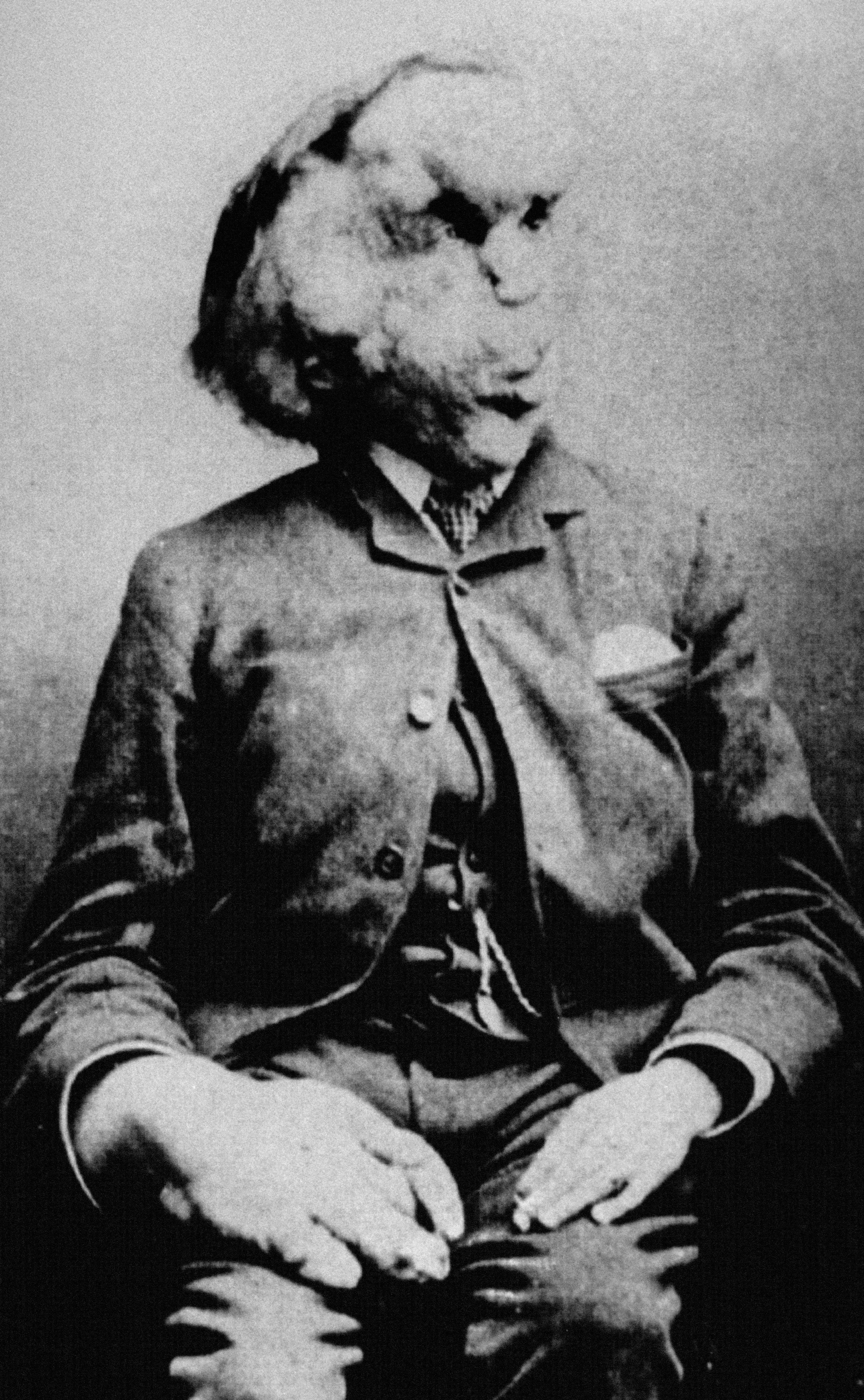

Lizard Man – like the Elephant Man and so many others – would be perceived with a similar repugnance or horror right here on our very own deeply messed-up and resolutely superficial planet. Unless we were blind, we would naturally shy away (or worse, stick around long enough to heap scorn and derision on the poor guy). Did anyone ever believe in the soul? Personally, I give credit to the mighty invisible soul of Lizard Man – but, in reality, no one else does. Are you going to give Lizard Man a job? No. Are you going to marry Lizard Man? Of course not. How often are you even going to hang out with Lizard Man?

The fact is that we take skin immensely seriously. “Only skin deep” doesn’t get much deeper. We judge and classify people by their skin tone (and whether or not it’s scaly). Maybe we don’t mean to but we do. We obsess about appearances, our own and others’. The philosopher Jean-Paul Sartre tells of how, when he was very young, with his long blonde curly locks, he was known in his family as “the angel”. Then one day when his mother was out shopping his grandfather took him off to the barbers to get a proper haircut. Young Poulou (his nickname) greets his mother happily on her return, but she runs up the stairs and throws herself on the bed sobbing hysterically – for he has been revealed, by the haircut, as the ugly little boy he really is. As in an inverted fairly tale, he is turned from “angel” to “toad”. An all-time bad hair day. And Sartre realises (in what is the origin of his theory of existentialism) that he has been objectified and evaluated in the gaze of the other – or mother. Hell, he realises, is other people.

We don’t see, we interpret, we confer meaning on what is intrinsically meaningless. Romance is a form of over-interpretation of sense data

Western philosophy, from the similarly ugly Socrates on, has railed in vain against our over-preoccupation with mere appearance. Surely truth must lie beyond the realm of maya (as the Buddhists would say)? Despite which we continue to judge books (i.e. fellow earthlings) by their covers. But now science is finally coming to the rescue by zooming in on the reality of skin and exploding our shallow perceptions for the delusions they are.

Skin, it should be said, is a relatively recent development in human history. It was always there, but – just as in the case of the infant Sartre – we took no notice of it because it was covered in hair. We didn’t even notice the hair particularly because it was all over the place and a common denominator of our primordial species. Then, between one and two million years ago, our hair started falling out – we had the haircut – and the truth of skin was revealed. We became, for the first time, naked apes: physiologically, we were cooler and could run further, because we developed eccrine sweat glands. Psychologically, we enjoyed and sought out the sensation of skin-on-skin contact.

Our humanoid ancestors were all, to begin with, dark-skinned. We had to be, roaming around the savannahs of east Africa in a sun-drenched environment. We know – thanks to brilliant genetic detective work – that the evolution of dark skin, generated by permanent melanin pigmentation to protect our now mostly hairless bodies, dates to roughly 1.2 million years ago. Babies and young children had the lightest and smoothest of skins. Females, statistically, tended to be paler than males. But for well over a million years, amazingly enough, we were not racists. We were not even speciesist (given the carnal encounters with Neanderthals). There was skin but colour did not yet exist as a system of semantics.

Then, less than one hundred thousand years ago, homo sapiens started taking the injunction to go forth and multiply more seriously. We roamed further afield. The mass exodus took us further south and north. Eventually, given enough time, we would spread all over the planet, up into Europe and Asia, finally down through the land mass of the Americas or hopping over to Australia, even voyaging across the Pacific, and venturing into the Arctic (we had worked out the art of clothing by this stage too, so we were no longer entirely naked apes). As we went our skins adapted to the different physical environments by a delicate and precarious balancing act. On the one hand we needed Vitamin D to keep the whole show on the road (vital for reproductive purposes and one reason why women had paler skin) and therefore skin had to let the light in, but we also needed to protect against damaging UV rays, and thereby preserve vitamin B and DNA, so skin had to darken up. Every colour we could come up was a compromise between conflicting imperatives, the selection depending on latitude and the level of solar exposure. The higher the UVR, the greater the pigmentation, the lower the “reflectance”.

Columbus and the Conquistadors were a disaster in the fate of humanity. The “voyages of discovery” were an exercise in self-aggrandisement and other-shaming. Within a century, Queen Elizabeth I’s Privy Council proposed expelling “blackamoores” from England. We observed differences of colour and on the back of them erected an immense apparatus of discrimination, a hierarchical chain of being, with “civilised races” lording it over “savage races”, in which politics, commerce, philosophy, religion, literature were all complicit. And, it should be added, science too. Science offered to prove and justify assumptions of racial superiority.

As Nina Jablonski, the anthropologist and author of Skin: A Natural History, and Living Color: The Social and Biological Meaning of Skin Color, says, “Scientists are hubristic. They like to think they stand above their own culture and are devoid of prejudice: but they aren’t. It’s a complete illusion. Good scientists are the ones who recognise their own cultural conditioning.” Sometimes science – or scientists – were in cahoots with the slave trade.

Jablonski stresses how visual we are as a species, especially if you compare us with, say, dogs (which have a vastly superior olfactory system). I suspect that the emergence of skin had a lot to do with the emphasis on vision: we just had more to look at and admire than ever before. A large chunk of our brains (more than 50 per cent of the cortex) is dedicated to processing visual information. “I see!” one says, as if that meant that you had attained the truth. The reality of sight is that it is limited and we overestimate our abilities. We detect less than “a thousandth of one percent” (as EO Wilson says) of all the energy and data flowing around and through us. What we can see occupies only a narrow band (wavelengths from 400 to 750 nanometres) on the electromagnetic spectrum. Infra-red, ultra-violet, X-rays, radio waves, gravitational waves, and all the manic mayhem of the quantum realm – we are blind to it all. But we over-compensate for our inadequacies by making up stories to go with the sparse particles of information we manage to pick up.

As Jablonski says, “we are suggestible”: there is no such thing as raw, unmodified percepts. Sense data are thoroughly warped and permeated with our assessments, bizarre and ill-informed though they are. We don’t see, we interpret, we confer meaning on what is intrinsically meaningless. Romance is a form of over-interpretation of sense data; so is fear (phobias and philias alike, you might say). We occupy a hyped-up (and hyped-down) ethico-aesthetico-ophthalmic world in which we cannot escape discriminating between beauty and ugliness, good and evil, on the basis of little or no evidence. “We like people who look a certain way and we label them celebrities,” says Jablonski. By the same token, we are “vain primates” and full of ourselves, even though crippled at the same time by a neurotic self-dissatisfaction that causes us to want to alter or “rectify” what we are. We have a love-hate relationship with ourselves.

It is this quirky cocktail of eccentricities has led us to become “colourists”. Colourism is rampant around the world. The late, great Michael Jackson was one of the best-known of colourists. He may well have suffered from vitiligo, that caused his skin to vary in pigmentation. But what is certain is that he used a variety of bleaching products designed to lighten his skin tone. Parts of Asia and Africa are populated by people of the Jackson tendency. Japan, by way of progressive selection for paleness over centuries, has actually induced a genetic shift in the population as a whole. In many cultures, lightness of skin tone has been associated with social status: rugged peasant types have been outdoors sowing seed and ploughing, while only the affluent and the leisured could have afforded to stay indoors out of the sun, preserving the skin from solar damage.

“Colourism is huge on the sub-continent,” says Farah Naz. She is British, of Asian ancestry, studied biochemistry at Imperial College, and is the founder of EX1 cosmetics, which caters specifically for darker skin tones (but also worn by Adele). She has skin a shade darker than her sister. Her wider family consists of people with blue eyes, hazel eyes, her own very dark eyes (“about as close to black as you can get”), and a variety of skin colours. But some of the older generation among her own family still assume that lighter is nicer. “There is a huge multi-billion dollar industry around the world dedicated to skin lightening,” she says. Most of the products on offer are toxic. But people use them anyway. “Unfortunately it’s an aesthetic that has taken hold.” Her range of cosmetics is intended to counterbalance the bias of the industry in favour of lighter European skin tones.

We’ve all been duped by a propaganda exercise from around the mid-18th century on. It paid to believe in a hierarchy of skin – it benefited mercantile interests

In many cultures, when future mothers-in-law look at potential brides, regardless of caste, skin colour is the first thing they look at. As soon as people realised fairness could result in them being more favourably treated, lightening became big business. We can talk of the “fallacy of fairness” but it’s self-perpetuating. A few years ago the Chief Minister of Goa, Laxmikant Parsekar, is reported to have told striking nurses that they should stop protesting in the streets on the grounds that the hot sun would make them “dark” and thereby “ruin their marital prospects”.

“It’s a paradox,” says Naz. “When we are supposed to be so woke and embrace what we are. When you can’t use the word ‘flaw’ any more [in our line of business] – you can’t even say ‘enhance’. And yet we are still obsessed with appearance. We still have this association of higher attractiveness with lightness. It’s not something that’s going to change overnight.” She says she has often noticed how people who have bleached the melanin out of their faces and hands, as soon as they roll up their sleeves or unbutton a shirt, reveal darker skin on other parts of the body.

At the other end of the spectrum, even in the context of an explosion in skin cancers, there is still a lingering preference among people with lighter skin types to appear healthier by acquiring an artificial tan, via either tanning parlours or spray tan. Which, to cite only the case of one recently retired US president, can look absurd. As Jablonski puts it, without beating about the bush: “Getting a tan or bleaching our skin is stupid, it’s really dumb.” The emergent field of “psycho-dermatology” covers a range of phenomena, from how our anxieties feed into our skin to how the state of our skin affects our state of mind. But it ought to include the madness, the OCD distortions, of our highly subjective mental colour schemes.

There have been numerous attempts to classify skin colour types, which have been inevitably inadequate and have typically emphasised the more European section of the spectrum, wrapping a whole apparatus around a limited subset of knowledge. In the 20th century the Von Luschan system produced 36 ceramic tiles that scientists carried around the world with them trying to find a match with skin tones. The cosmetics industry still goes by the Fitzpatrick scale, dating from the 1970s, specifying six “skin types”. Both Jablonski and Naz refer to these taxonomies as “antiquated”.

Angélica Daas in her pioneering photographic project, Humanae, captured the faces of 4,000 volunteers in 20 different countries set against a smooth industrial palette, Pantone. It showed that there is no black, there is no white, no yellow and no red either, except in our mad imaginings. In reality every colour is interwoven with other colours.

Using the latest reflectometry technology and a massive database, Nina Jablonski and others are now working towards a new, more objective taxonomy of skin colour, driven as Jablonski says by “a swell of public events that includes but it is not limited to the Black Lives Matter movement.” The reality is that we are faced with limitless polychromatic variation in skin tone. But we can’t take too much reality. Or hybridity. So we boil it down and simplify and add prejudice on top. But the science of skin colour has made tremendous strides in the past half-century. Scientifically, we have already landed on the moon, but semiotically we are still relying on horse and cart. Everything you thought you knew about skin turns out to be wrong. Maybe if we could only increase awareness of the true complexity of colour then we could begin to decontaminate our perceptions and categorisations.

“When people say we are inherently tribal or racist, I say, no we’re not,” says Jablonski. “Our values are not ancient. But we are susceptible to interpretation. We’ve all been duped by a propaganda exercise from around the mid-eighteenth century on. It paid to believe in a hierarchy of skin – it benefited mercantile interests. Some of our constructs do not conduce to human welfare and lead to egregious injustice.”

Read More:

Teams of skin specialists, including Jablonski’s, will be publishing papers on the subject later this year. But I can’t wait for the app that will tell me about my own skin, which is as different as DNA from anyone else’s, even if I still need to slap sunblock on. Maybe in the future we will be less “oppressed by the figures of beauty” (as per Leonard Cohen’s Chelsea Hotel). Colourism is, as Jablonski says, “a learned routine”. And if we can learn it, we can unlearn it too. “We’re not just holding up a mirror,” says Jablonski. “Soon we will be able to wipe the mirror clean and see what’s really there.” For now we see through a glass darkly, but then face to face.

Andy Martin is the author of ‘Surf, Sweat & Tears: the Epic Life and Mysterious Death of Edward George William Omar Deerhurst’ (OR Books)

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments