New device converting infrared heat to electricity could lead to solar power at night

Scientists make use of infrared emission that happens at night from the Earth into outer space

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Scientists have successfully tested a device that is capable of converting infrared heat into electrical power.

The device, described last week in the journal ACS Photonics, is based on technology similar to that used in night-vision goggles and may lead to new ways of harnessing the Sun’s energy in the dark of night.

While solar energy warms the Earth during daylight hours, it is lost into the coldness of space when the sun goes down.

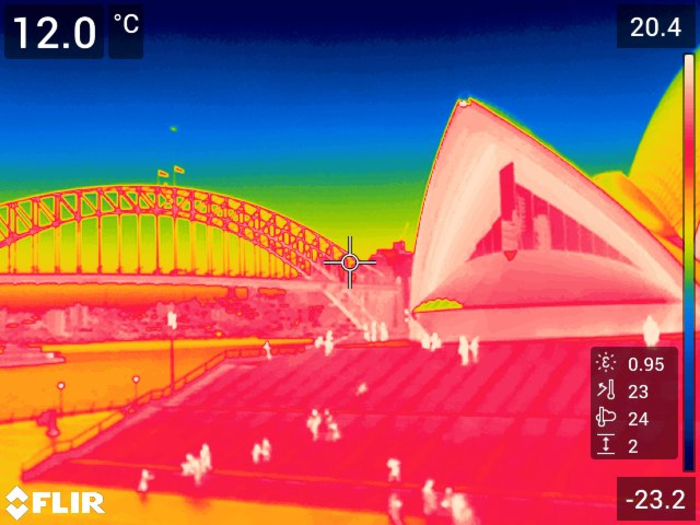

In the new study, scientists, including those from the University of New South Wales in Australia, have tested a device that can convert infrared heat into electrical power that uses a power-generation tool called a ‘thermo-radiative diode’, which is similar to the technology in night-vision goggles.

“In the late 18th and early 19th century it was discovered that the efficiency of steam engines depended on the temperature difference across the engine, and the field of thermodynamics was born,” explains Nicholas Ekins-Daukes, a co-author of the study.

“The same principles apply to solar power -- the sun provides the hot source and a relatively cool solar panel on the Earth’s surface provides a cold absorber. This allows electricity to be produced,” he added.

The new device still uses solar power, which hits the Earth during the day in the form of sunlight and warms up the planet.

It makes use of infrared emission that happens at night from the Earth into outer space.

In this case, scientists say, the Earth is the comparatively warm body, with the vast void of space being extremely cold.

“Photovoltaics, the direct conversion of sunlight into electricity, is an artificial process that humans have developed in order to convert the solar energy into power. In that sense the thermoradiative process is similar; we are diverting energy flowing in the infrared from a warm Earth into the cold universe,” Phoebe Pearce, another co-author of the study, said.

In the same way that a solar cell can generate electricity by absorbing sunlight emitted from a very hot sun, the thermoradiative diode generates electricity by emitting infrared light into a colder environment. In both cases the temperature difference is what lets us generate electricity,” Dr Pearce added.

While the amount of energy produced through this new test is small – roughly equivalent to 0.001 per cent of a solar cell – they say the proof of concept is significant.

“We usually think of the emission of light as something that consumes power, but in the mid-infrared, where we are all glowing with radiant energy, we have shown that it is possible to extract electrical power,” Dr Nicholas said.

“We do not yet have the miracle material that will make the thermoradiative diode an everyday reality, but we made a proof of principle and are eager to see how much we can improve on this result in the coming years,” he added.

Researchers are currently working on creating and refining their devices to harness the power of the night.

The say the new findings are a first step in making specialised, more efficient, devices that could capture this energy at much larger scale.

“By leveraging our knowledge of how to design and optimise solar cells and borrowing materials from the existing mid-infrared photodetector community, we hope for rapid progress towards delivering the dream of solar power at night,” Michael Nielsen, another co-author of the study from UNSW, said.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments