CrowdStrike isn’t the only cyber company that could trigger global meltdown the second they fail...

As the world recovers its losses since an unprecedented outage disrupted flights, hospital appointments and bank payments, Chris Stokel-Walker looks at what other companies could bring our lives to a halt at the flick of a switch and who is behind them

It is just over a week since the mammoth outage that grounded flights, cancelled hospital appointments and operations, and derailed supermarket and bank payment systems last week.

More than 8.5 million computers running Microsoft Windows were left locked in a state of perpetual start up as the blue screen of death (BSOD) spread around the world – triggered by a fault in a file CrowdStrike, a cybersecurity firm, provided as a third-party to Windows that was ironically designed to keep things safe.

Before the panic ensued, few had ever heard of CrowdStrike, but in just a few hours the company’s reputation was in tatters. Its stock price closed trading on 22 July at $263.91 (£205.30), down a third in less than a month. Its CEO George Kurtz was forced to issue an immediate and unreserved apology for the doomed software update which caused the outage, and the $10 (£8) Uber Eats vouchers he has since offered as a make-good is unlikely to cut it.

It is now officially the biggest outage in history and “a reminder of the fragility and systemic ‘nth-party’ concentration risk of technology that runs everyday life: airlines, banks, telecoms, stock exchanges and more,” says Aleksandr Yampolskiy, CEO and co-founder of SecurityScorecard, a firm that tracks and rates cybersecurity across organisations.

His company’s data suggests that just 15 companies account for nearly two-thirds of all cybersecurity products and services – meaning if anything unforeseen went wrong with them, like it did with CrowdStrike, they have the potential to bring the world to a halt.

But who are some of these biggest companies and who is behind them?

Fastly

Vital to your day-to-day experience in the digital world, like CrowdStrike, the cloud computing services provider was founded in 2011, and works by providing so-called “edge cloud” services: bringing storage of files that users encounter online closer to them.

“Services that offer cloud processing at the edge are increasingly important to the speedy delivery of content such as live video and are expected to be central to the future expansion of AI on our devices,” a cybersecurity expert at Gresham College said. “Tech companies have a vision of a decentralised internet of semi-autonomous connected things, and this relies on instant processing that doesn’t lose time through transmission to and from a central server.”

Fastly’s content delivery network (CDN) is crucial to that instant processing – and things can go catastrophically wrong when it doesn’t work. Instant processing means that you see the website or YouTube video you click on immediately, rather than waiting.

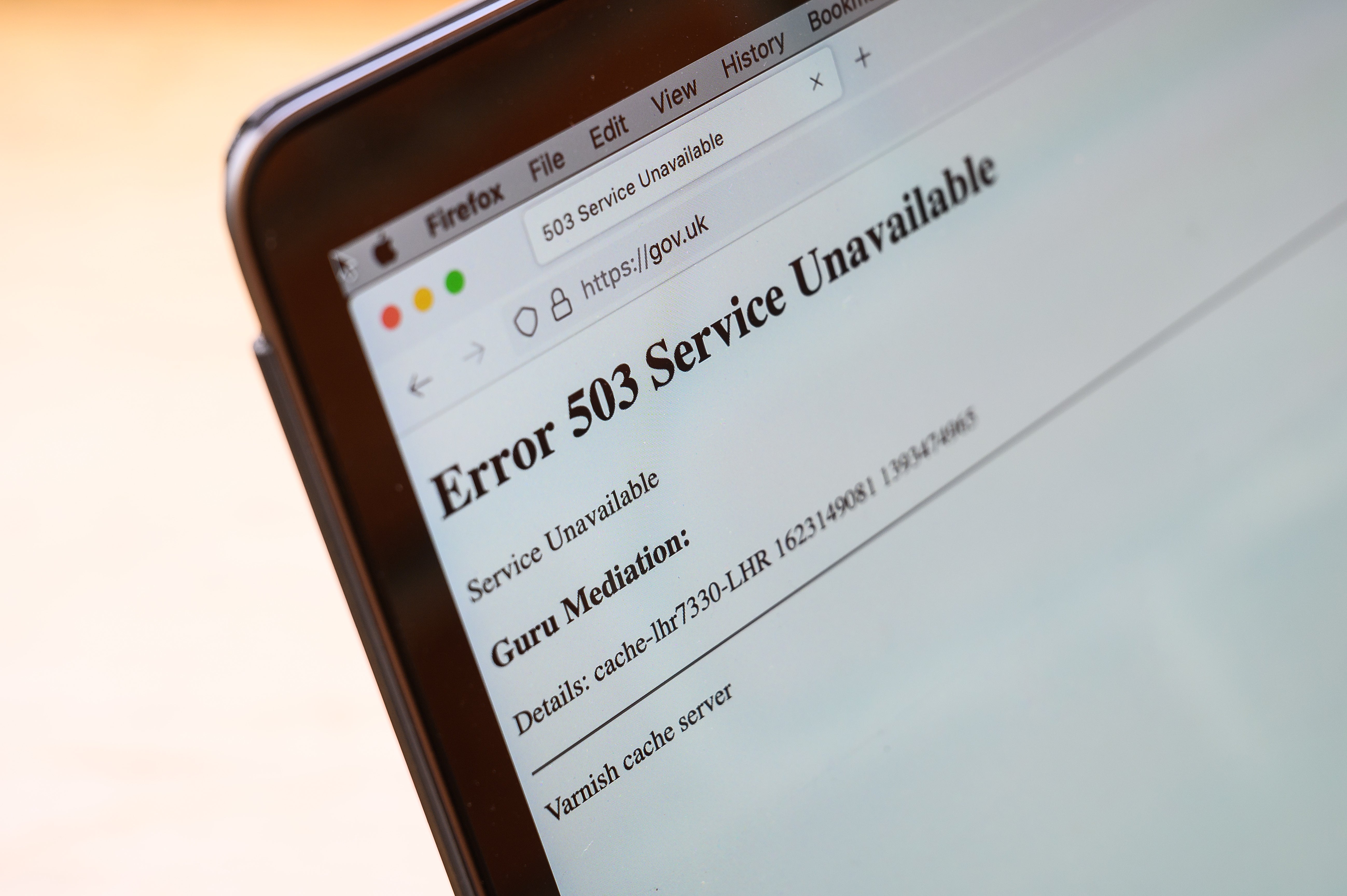

A hitch in the Fastly CDN service can be annoying – but it going offline can be catastrophic, as we got a taste of in June 2021. As with CrowdStrike, a misconfigured file was pushed out to the company’s systems and took them offline – along with the UK government website, PayPal, Amazon, Reddit, Twitch, CNN and a number of other news websites, all of which used Fastly as their CDN provider.

The company’s founder is Artur Bergman, a Swedish-American entrepreneur who, prior to Fastly, set up the company then known as Wikia, which develops fandom-based Wikipedia-style sites on everything from anime to pro wrestling. Bergman is now Fastly’s chief architect and remains involved in the company. Fastly’s net worth as of 25 July is $1.05bn (£820m).

The OpenSSL Project

The OpenSSL Project is a volunteer-run organisation that plays an outsized role in the security of everything we do online. Whenever you see the padlock on your web browser at the point of checkout, the transfer of data taking place is secured using OpenSSL – meaning if it were to go down, in theory hackers could snoop on every credit card transaction or payment you make online.

For something so high stakes, experts warn that OpenSSL is underfunded and under-resourced. “OpenSSL is classic,” says Alan Woodward, professor of cybersecurity at the University of Surrey. “It’s free and embedded in all sorts, but is maintained by one man and his dog.” (That’s not quite correct, but for a long time, including during a 2014 incident that left large parts of the internet insecure, it was run by two men named Steve.)

OpenSSL is an open-source tool, which means its code is freely available, and it can be freely used. “The theory goes that being open-source, millions of people scrutinise it, so mistakes are found quickly,” says Woodward. But that’s not always the case. “It’s written in C++ [a complicated computer language] and involves highly complex crypto, so there are few qualified to have a proper look at it,” he says. “It has had some real howlers before.”

The irony of the OpenSSL Project is that it’s a hobby that became an integral part of the underpinning of the web. While enormous companies like Google and others rely on it, the people who maintain it aren’t well-funded, and aren’t rich. They’re simply dedicated software engineers trying to keep us all safe online.

NATS

Around four per cent of flights worldwide were cancelled thanks to CrowdStrike’s outage, with US airline Delta’s CEO saying that they expect their services to be disrupted for a few more days as they try to unpick the issues that resulted from the mass problem.

But the chaos that unfolded at airports around the world is just a small taste of what could happen if the routing systems that keep air traffic controlled were to malfunction. In the UK, the company that could bring the world to a halt if it faced issues is NATS, the 60-odd year-old company that oversees air traffic control in the UK and provides services to 14 different airports.

“NATS is critical to the delivery of safe, reliable air traffic services in the UK,” says independent aviation analyst John Strickland. It relies on computer systems in order to carefully manage the arrival and departure of flights from UK airports – sometimes in fractions of a minute at the busiest airports. And if anything goes wrong with its systems, then it has catastrophic effects.

That isn’t a hypothetical suggestion: it has happened. “We saw the consequences of a failure last year,” says Strickland. In August 2023, a small glitch from a single flight plan took the NATS computer routing system offline. In all, 700,000 passengers were affected, according to a Civil Aviation Authority report into the incident.

“Flight operations were brought to minimal levels with thousands cancelled, causing massive disruption to airlines and their customers,” says Strickland.

Martin Rolfe, the CEO of the Fareham-based company, which made nearly £250m in profit before tax in the 2024 financial year, earned £1.16m for running the company in the same year – down from £1.39m the year before.

ICANN and Verisign

Few people realise what happens when they type a URL like “independent.co.uk” into their web browser. The words are converted into a series of numbers called an internet protocol (IP) address, using a massive system called the Domain Name System, or DNS.

“DNS is essentially the internet’s address book, the thing that turns “Google.com” into the right sequence of numbers – its IP address – that sends you to Google’s servers when you type it,” says James Ball, author of The System: Who Owns the Internet, and How It Owns Us.

DNS servers are run by various different companies, but three of the 13 largest ones, called the “root servers”, are run by ICANN, a non-profit of just over 400 staff founded in 1998, and Verisign, a Virginia-based private company founded by D James Bidzos.

“If you mess with the big DNS servers, it’s like updating an address book to point somewhere else,” explains Ball. “It means the new address is shipped right across the internet and can take hours or days to change. It can either point you to nothing or else to something malicious – a fake site that looks like the real one but steals your details.”

But if hackers went a step beyond tampering with the DNS servers and instead brought them offline, chaos would ensue.

“When that’s one of the DNS servers at the heart of the internet it can stop you reaching anything,” Ball says. “All of the servers are still there and online. It’s just that no one can find them.”

Amazon Web Services

Amazon may be best known to most of us for stocking any product you can think of in the world-renowned “anything store”, but its influence reaches into the most vulnerable parts of our lives, via Amazon Web Services, or AWS for short – the company’s hugely profitable cloud infrastructure arm.

AWS provides storage capabilities to companies looking to host their websites without having to install the computer hardware to do so themselves. Most websites are hosted by a cloud infrastructure provider. And, in this sector, Amazon is the big beast.

Across the industry, cloud infrastructure service providers had $76bn (£59bn) in revenues in the first three months of 2024, according to Synergy Research Group. With Amazon founded in 1994 by Jeff Bezos – who is currently worth a reported $200bn (£156bn) – you can see how it’s not a bad business to be in.

But sometimes its services go offline for a short period due to errors – most recently in June 2023, when Nike’s website, as well as the ordering apps for McDonalds and Burger King, all went offline. Hosting 31 per cent share of the market, you could see how a wider problem with some of the world’s biggest websites could ripple out beyond drive-through burgers to something potentially much more life-affecting.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments